The Rhythm for Reading blog

All posts tagged 'Music'

Musical teamwork and empathy

28 February 2024

Image credit: S.B. Vonlant via Unsplash

Teamwork

There’s tension in teamwork! On the one hand there’s the idea that ‘teamwork makes the dreamwork’, pointing to the ideal situation in which everyone pulls together to attain goals that are shared and for the good of the whole community - for instance in a social enterprise. The maxim, ‘There’s no ‘I’ in team’ tells us that people sometimes contribute to teamwork with other intentions - perhaps they see it as an opportunity to outshine, usurp or even exploit the efforts of others.

Let us think for a moment about a community of traditional hunter gatherers, researched by anthropologist Jerome Lewis at ULC. They have life ways built on teamwork: - Women and men carry out their day-to-day roles in separate groups and the two groups alternate in terms of taking on the responsibility for leadership and decision-making. In this way, the community maintains a rhythmic balance, like the swing of a pendulum, between the perspectives of the men and then the women. The elders of the community, particularly the women, encourage everyone to ridicule any young person who wants to be louder, faster or smarter than others in the group.

The qualities of teamwork have also been studied by neuroscientists and there are no surprises here. Teamwork involves joint action, communication and empathy: people’s actions naturally fall into coordination with one another. We see this in social situations where there is obvious mirroring - one person sips water from a glass and then others at that table do the same, perhaps as a symbolic intention of unity.

On the one hand, there are distinct disadvantages to group behaviour and teamwork, because imbalances within the group can generate a false sense of security, potentially affecting many people:

- ‘groupthink’ - when people are not able to discuss matters openly and one opinion dominates,

- bias - when clear thinking is sidelined by ideology and the whole group loses touch with reality,

- double standards - when a minority abuse the value system held by the group to dominate and repress the majority.

On the other hand, the advantages of teamwork and a sense of group membership are beneficial in the long term for our health and well-being. For example, it is easier for us to coordinate repetitive actions with others and to communicate regularly in small groups. This is because as humans, we are hard-wired to rely on group effort to guide both our day-to-day behaviour as well as our longer term goals. Teamwork is advantageous in the long term in the following ways:

- it is economical in terms of energy expenditure,

- coordinated actions look and sound impressive to outsiders,

- predators will likely be deterred, and

- people feel they belong and are safe.

Musical teamwork

In both contemporary western cultures and extant hunter gatherer societies, humans are coordinated in time by feeling a shared rhythm - whether that is via a physical action, a chant or a song. The repetitive nature of many actions means that the movement is not only coordinated in time but also refined in space.

This is a natural phenomenon that applies to most species - for example, bees secrete wax and form hexagonal cells in honeycomb because a hexagon shape allows for economic use of repetitive, rhythmic movement and energy, without compromising the stability and strength of the cell walls. We see a stylised version of this in formal military displays around the world, and a more relaxed version in informal crowd behaviour (such as a ‘Mexican wave’ or clapping in time) at cultural events for example at a sports stadium - whether enjoying a match or a pop concert.

The formation of a group identity in the context of working together involves mutual trust, respect, a desire to achieve results through coordinated precision and also the flexibility that is needed to achieve an optimal result. In musical teamwork, this level of cooperation is practised as a discipline ‘for its own sake’ because the people involved share joint musical goals. These might be modest such as journeying through a new musical score, or writing a new song together. The joint experience of traversing the musical ‘unknown’ is mysterious and requires coordination and coherence - similar to navigating a cave in the dark. Or, the goal might be more aligned with artistry, such as working together to balance all of the nuances of a known piece of music, so that the performance of a particular work comes across as a sublime entity of perfectly structured, balanced, ’architectural’ proportions, although in real time.

So, in describing different types of joint action in music - as in many things - it becomes obvious that some teams could be described as ‘elite’ and some as ‘inclusive’. In both groups (provided there is a sense of joint action, trust and positive teamwork) the neuropeptide, oxytocin (aka ‘the love hormone’) works quickly to build bonds between people and to form what are known among social psychologists as ‘in groups’ and ‘out groups’ (a power imbalance usually favours the ‘in group’).

For instance, in the Rhythm for Reading programme, we uphold an inclusive ethos. This is very important as everyone involved must feel that they can play a meaningful role in contributing to the effort of their group, each week. When, on occasion, a teacher has tried to introduce a new child into a group of ten children, or to swap two children between different groups (there may be six groups of children taking part in one school), the trust and the bonds in the affected groups may be dissolved, probably because of the influence of oxytocin on group identification..

So, to sum up, teamwork is an important and impactful aspect of the Rhythm for Reading programme.

Musical teamwork and empathy

An abundance of research findings point to the ‘prosocial’ impact of joint music-making (Hallam and Himonides , 2022). Being involved in music making requires sustained and coordinated joint action. For example, each person is aware of their own contribution, but they also have oversight of, as well as respect and responsibility for, the overall effect. In other words, each person would be listening and personally invested in the balance of the music in terms of its:

- musical texture - anticipating and blending their own sound in proportion to the sounds of others,

- pitch and melodic line - anticipating and aligning a single pitch or a melody with the pitch of others,

- rhythm and tempo - keeping in time with others, anticipating and contributing to the vibrancy of shared rhythm, and

- harmony - phrasing and blending their own sound within a shared ownership of harmony and structure.

In the anthropological work of Jerome Lewis, joint music making within the community of hunter gathers involved singing to their homeland - the nature around them in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Each level of richness of the equatorial forest was represented in their complex music, so that within communal music making, many rhythms and melodies were sung, balanced, and harmonised together. If one person protruded or was conspicuous, the precious balance of the musical ecosystem was lost and that person would be known as, ‘an energy thief’.

In music education in the UK, different types of music tend to require different kinds of musical interaction. These might include:

- playing in time with others, focussing mainly on synchrony and tight coordination,

- holding a completely different line and harmonising, with additional demands on cognitive control, or,

- alternating with each other, with room for greater individual expression, improvisation and flexibility.

Each of these examples emphasises what could be loosely described as a different musical skillset, but at the heart of all of these examples is the need for: empathy and ‘theory of mind’ - being able to read the intentions of others and respond accordingly,

Musical notation, teamwork and empathy

- If we feed a child nourishing food, we can say this has enhanced their health.

- If we place a child into stimulating musical training, we can say this has enhanced their empathy.

- If we place a child into an intervention which teaches them to read musical notation, we can say this has improved their reading skills.

There is a clear pattern of cause and effect, but millions of years of evolution have primed us to respond to optimal experiences that promote health, empathy and communication. This is why children are known to respond positively to an enriched environment (and why an enriched environment is also known to accelerate learning in animals, such as mice and rats).

A more worrisome situation arises when children from disadvantaged social backgrounds, whose fundamental needs of adequate nutrition, shelter and safety (physical, social and psychological), may not have been addressed, are placed into underspecified musical interventions where they are expected to thrive. This may be why many music education research studies have achieved such mixed results (see Hallam and Himonides, 2022 for a comprehensive review).

Closing thoughts

In the Rhythm for Reading Programme, the safety of the children is always the top priority, and this includes ensuring that on a weekly basis they experience a strong sense of:

- belonging - through working as a team, and coordinating with the specially composed music in a consistent way,

- fluency and ease - through reading simple notation enriched by patterns, repetition and novelty,

- happiness and enthusiasm - through participating in shared moments of collective joy.

To read about the extraordinary impact of the Rhythm for Reading programme on children’s reading comprehension click here.

To book a call and discuss group teaching and the needs of children in your school, click here.

If you enjoyed this post, keep reading!

Breath is an important part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. We use our voices as a team in different ways and this engages our breath. In the early stages of the programme we use rapid fire responses to learn the names of musical notes and our breath is short, sharp and strong - just like the sounds of our voices.

Confidence and happiness in the Rhythm for Reading programme

This post describes the tenth of ten Rhythm for Reading programme sessions. By this stage in the reading intervention, everyone in the group can sight-read both simple and comparatively complex music notation with ease and confidence. To do this, our eyes are glued onto the board, our voices are synchronised and we’ve gelled through teamwork.

By nine years of age, children have assimilated a vast amount of information about their culture simply by learning through experience. Enculturation is a particularly powerful form of deep learning that shapes children’s attitudes and perceptions of the world in which they are growing up. Through working in many schools, I’ve observed that by the age of nine years, children have, through this process of enculturation developed a strong emotive response to the concept of ‘teamwork’.

Learn to read music and develop executive functions: The exception rather than the rule

The Rhythm for Reading Programme creates an environment that allows pupils to focus their attention right from the start. They learn to read music by repeating, reviewing and practising key concepts each week, consistent with the principle of ‘spaced practice’. Consistent rehearsal of musical notes using visual images, as well as hearing and saying the note names, illustrates the principle of ‘dual coding’. The programme is built on a cumulative structure that prioritises fluency, as well as a light ‘cognitive load’ and there is a gradual increase in the complexity of tasks within the context of working together as a strong and enthusiastic team.

References

Hallam, S. and Himonides, E (2022) The Power of Music: An exploration of the evidence, Cambridge: Open Book Publishers

NB References to Jerome Lewis are from personal notes taken during public lectures given by Radical Anthropology Group, Department of Anthropology, University College London.

Learn to read music and develop executive functions: The exception rather than the rule

17 January 2024

The narrowing of the curriculum has squeezed the arts and humanities and this is likely to affect pupils from a lower socio-economic status (SES) background more than relatively advantaged children, according to the Sutton Trust (Allen & Thompson, 2016). In England, headteachers are tasked with challenging the effects of economic disadvantage by ensuring children are able to access a broad and balanced curriculum, rather than an impoverished one. However, given that the allocation of teaching time is such a precious resource, how might primary schools devise a curriculum that includes musical notation? Traditional approaches are time-consuming and use complex mind-boggling mnemonics that are not sufficiently inclusive. However, a rhythm-based approach avoids cognitive loading and requires short weekly sessions of about ten minutes. This uses short, sharp quick-fire responses that are fun and facilitate group learning.

Teaching musical notation with a sense of mastery

The Rhythm for Reading Programme creates an environment that allows pupils to focus their attention right from the start. They learn to read music by repeating, reviewing and practising key concepts each week, consistent with the principle of ‘spaced practice’. Consistent rehearsal of musical notes using visual images, as well as hearing and saying the note names, illustrates the principle of ‘dual coding’. The programme is built on a cumulative structure that prioritises fluency, as well as a light ‘cognitive load’ and there is a gradual increase in the complexity of tasks within the context of working together as a strong and enthusiastic team.

There is minimal input in terms of ‘teacher talk’. Instead, explicit instructions from the teacher, based on the rubrics of the programme outline the specific details of each task. This approach is known to support novice learners and a clear expectation on the part of the teacher is that every child contributes to the team effort and is key to the programme’s impact.

Teaching musical notation and cultivating executive functions

The Rhythm for Reading Online Training Programme offers individually tailored CPD.

Teachers are immersed in a completely new knowledge base and a comprehensive body of work, including theory, research and practice, that has successfully evolved over a period of three decades.

The Rhythm for Reading approach stimulates children’s executive functions using simple repetitive techniques that feel like a fun group activity and are easy for all children to master.

The programme has been shown to transform reading development in:

- young people with severe learning needs in a special education setting

- Pupil Premium children in mainstream schools

- children with specific learning difficulties

- children who simply need a ‘boost’ in their reading

By following the simple rubrics and rhythm-based exercises of the online programme, teachers are able to accelerate children’s reading development and cultivate their executive functions during ten weekly sessions of about ten minutes.

Teachers need to practise using these fresh and exciting new teaching methods for at least a couple of terms. Ongoing mentoring support is available throughout the programme, as is follow-up support. For further details click here.

As teachers develop a practical understanding of how to nurture children’s executive functions through rhythm-based exercises, they feel empowered by changes in the children’s progress.

Reading fluency is monitored by teachers throughout the programme using a dedicated ‘Reading Fluency Tracker’ which takes two minutes to complete each week. There is also, if needed, an option to focus on deeper levels of assessment of learning behaviour.

Teacher enrichment and reflexive practices are keystones in the CPD of the Rhythm for Reading programme and there is a strong emphasis on supporting teachers’ well-being. A workbook is available for teachers to record their personal experiences of the programme and these can be referenced in weekly one-on-one mentoring calls.

Research Studies in Music Education

Research on the benefits of music training to executive function is inconclusive. According to academics, the mixed bag of findings reflects differences in the types of musical activities. At present, the relationship between musical training and any effect on executive functions is unclear to the music education research community. However, based on a review of the latest research, academics offered this recommendation:

Ideally music lessons should incorporate skills that build on one another with gradual increases in complexity. (Hallam and Himonides, 2022; p.197).

Potential exists for each executive function to play an important role in music making as follows:

- Inhibitory control is essential to the element of teamwork in music-making, such as community singing, where people are encouraged to participate with others in a balanced and proportionate way.

- Cognitive shifting, also known as cognitive flexibility, is activated every time a change occurs in a melodic or rhythmic pattern, and also when the relationships between the musical lines or voices, also known as the texture, changes.

- Working memory is constantly activated in the same way that it would be in a conversation, with updating, assimilating and monitoring, as a person participates in the music.

- Sustained attention is necessary for the coordination of cognitive shifting and working memory. Just as interaction in a conversation is predictable at the beginning and the end, but may have a ‘messy middle’ (a loss of predictability), the same can be said to exist in music.

- To maintain the necessary level of sustained attention in the dynamic activity of music making, each performer engages inhibitory control of internal and external distractions.

In a particularly well-controlled, and therefore robust study, there were strong positive effects of musical training on executive functions, particularly inhibitory control among children (Moreno et al., 2011, cf. Hallam and Himonides, 2022).

Although the expressions, ‘getting lost in the music’ and ‘getting lost in a book’ are figurative and imply a perception that the external world has temporarily ‘ceased to exist’, there is also an implication that the individual has entered into a meditative ‘flow state’, suggesting that the executive functions are working together in a coherent and self-sustaining way.

Reading musical notation, reading a text and executive function

Given that musical notation as a symbol system that describes what should happen during music making, there is a strong logical argument for musical notation to act as a stimulus for activating executive functions.

A ‘Yes-But’ response resounds at once because the research literature is ‘mixed’ in terms of findings. Bear with me as I offer a few thoughts…

When researchers used a brain scanner to study the parts of the brain involved in reading musical notation, they asked professional musicians to read musical notes, a passage of printed text and a series of numbers on a five-key keypad (Schön et al., 2002, cf. Hallam and Himonides, 2022). Unsurprisingly, similar areas of the brain were activated during each type of reading activity. Over millennia humans have developed many symbol systems, including leaf symbols, hieroglyphs, cuniform, alphabets and emojis. This research is very reassuring as it suggests that the brain adopts a standard approach for reading different symbol systems. As there was no evidence that reading musical notation was any different to reading text or numbers, then presumably musical notation and other types of reading share the same neural structures. If this is the case, then this might explain an acceleration of reading skills in struggling readers after a six-week intervention in which children learned to read musical notation fluently (Long, 2014).

Reading musical notation differs from reading text or numbers in one important way: each symbol has a precise time value, which is not the case when we read words or numbers. However, when reading connected text or musical notation, there is an important element that is relates directly to rhythm, which is that musical phrases and sentences tend to be read within similar units of time. By coincidence (or by way of an explanation), this time window happens to fit with our human perception of the duration of each present moment.

So, given that working memory fades after about five to seven seconds of time have elapsed, we can understand that musical phrases and utterances in spoken language are closely tied to executive functions of working memory and sustained attention.

Reading musical notation and executive function

Many people’s experience of reading musical notation begins at the moment when they are learning to play a musical instrument. The physical coordination required to produce a well-controlled sound on any musical instrument draws upon sustained attention, working memory, and cognitive flexibility (adapting to the challenges of the instrument). The engagement of these executive functions in managing the instrument may leave very few cognitive resources available for reading notation, leading to frustration and a sense of cognitive overload.

Using the voice rather than an instrument offers a possible solution, as singing is arguably the most ‘natural’ way to make music. Learning a new song however, involves assimilating and anticipating both the pitch outline and the words before they are sung. As these tasks occupy working memory, it is possible that cognitive overload could arise if reading notation while learning a new song.

Chanting in a school context - a rhythm-based form of music-making that humans have practised for thousands of years, whether in protest or in prayer is relatively ‘light’ in terms of its cognitive load on working memory. All that is required is a short pattern of syllables or words. Repetition of the pattern allows the chant to achieve a mesmeric effect. This can be socially bonding, hence the popularity of chanting in collective worship around the world.

Although researchers have demonstrated that musically trained children have higher blood flow in areas of the brain associated with executive function (Hallam and Himonides, 2022 ), it is important that researchers specify the musical activities that activate executive functions.

Comparing the three options: learning an instrument, a song or a chant - it is clear that they could develop executive function in different ways.

Learning to play a musical instrument demands new levels of physical coordination, involves deliberate effort and activates all of the executive functions for this reason.

Learning a new song places a high demand on verbal and spatial memory (working memory) as the pitch outline and the words of a song must be internalised and anticipated during singing.

Learning a simple chant places minimal demand on cognitive load. This makes it is easy for individuals drop into a state of ‘autopilot’, allowing the rhythmic element of the chant to keep their focus and attention ‘ticking over’ without deploying executive function.

So, chanting, with its lighter cognitive load offers the most inclusive option for teaching musical notation in these settings:

- in mixed ability groups in mainstream schools

- among children with learning differences in mainstream or special educational schools

You might be thinking surely, ‘mindless’ chanting has no place in 21st century education? Yes, I would agree - but the exception to this notional rule would be this: chanting is appropriate for children with fragile learning and reading if they also display hypo-activation of executive function:

- weak attention,

- limited working memory

- poor impulse control

- slow cognitive switching

Children with weak executive functions are better able to learn to read musical notation using chanting (rather than playing an instrument or singing) for the reasons outlined above. A rhythm-based approach (using a structured and cumulative method) restores executive function and reading development among these children in a very short period of time.

According to Miendlarenewska and Trost (2014) enhancing executive functions through rhythmic entrainment in particular would drive improved reading skills and verbal memory: the impact of the Rhythm for Reading programme bears this out (Long, 2014; Long and Hallam, 2012).

If you enjoyed reading this post, keep reading:

A simple view of reading musical notation

Many people think that reading musical notation is difficult. To be fair, many methods of teaching musical notation over-complicate an incredibly simple system. It’s not surprising that so many people believe musical notes are relics of the past and are happy to let them go - but isn’t this like saying books are out of date and that reading literature is antiquated?

Musical notation, a full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection

Many years ago, I was asked to teach a group of children, nine and ten years of age to play the cello. To begin with, I taught them to play well known songs by ear until they had developed a solid technique. They had free school meals, which in those days entitled them access to free group music lessons and musical instruments. One day, I announced that we were going to learn to read musical notation. The colour drained from their faces. They were agitated, anxious and horrified by this idea.

Empowering children to read musical notation fluently

Schools face significant challenges in deciding how best to introduce musical notation into their curriculum. Resources are already stretched. Some pupils are already under strain because they struggle with reading in the core curriculum. The big question is how to integrate musical notation into curriculum planning in a way that empowers not only the children, but also the teachers.

Teaching musical notation, and inclusivity

For too long, musical notation has been associated with middle class privilege, and yet, if we look at historical photographs of colliery bands, miners would read music every week at their brass band rehearsals. Reading musical notation is deeply embedded in the industrial cultural roots. As a researcher I’ve met many primary school children from all backgrounds who wanted to learn to read music and I’ve also met many teachers who thought that reading music was too complicated to be taught in the classroom.This is not true at all! As teachers already know the children in their class and how to meet their learning needs, I believe that they are best placed to teach musical notation.

References

Allen & Thompson (2016) “Changing the subject: how are the EBacc and Attainment 8 reforms changing results? The Sutton Trust,

Hallam, S. and Himonides, E. (2022) The Power of Music: An exploration of the evidence, Cambridge, UK, Open Book Publishers

Long, M. (2014). ‘I can read further and there’s more meaning while I read’: An exploratory study investigating the impact of a rhythm-based music intervention on children’s reading. Research Studies in Music Education, 36 (1) 107-124

Long, M. and Hallam, S. (2012) Rhythm for reading: A rhythm-based approach to reading intervention. [MP282] Proceedings of Music Paedeia, 30th ISME World Conference on Music Education, pp. 221-232

Miendlarenewska, E. A. and Trost, W. J. (2014) How musical training affects cognitive development: rhythm, reward and other modulating variables. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7.

Moreno, S., Bialystok, E., Barac, R., Schellenberg, E.G., Capeda, N. J. & Chau, T. (2011). Short-term music training enhances verbal intelligence and executive function, Psychological Science, 22 (11), 1425-1433

Child development in 2024: Learning versus hunger

3 January 2024

I had planned to find a light-hearted piece of new music education research for the first post of 2024 and maybe a few fun facts. I considered a study on the benefits of chanting, another on whether rats feel groovy (and yes, rats do feel the groove), but eventually I chose a new piece of research on the benefits of singing to infants because it drilled down into a possible relationship between rhythmic movement and expressive vocabulary development (Nguyen and colleagues, 2023).

At the same time, I considered recent topical pieces on child development and education in the mainstream media. Suddenly, this post became much heavier as it was destined to contrast the challenges of struggling families against the privileges of those who shape music education as research participants.

In recent weeks, there has been coverage on the rapid rise of ‘baby banks’ (Chloë Hamilton, The Guardian Newspaper). These are like food banks, but specialise in providing free nappies, baby formula, clothes and equipment. We have 200 branches in the UK and just as the Christmas holidays were about to start, there was also a piece about headteachers reporting malnourishment among their pupils (Jessica Murray, The Guardian Newspaper).

Having delivered the Rhythm for Reading programme in schools that also function as community food banks, and having seen children faint from hunger while at school, I am in no doubt that nothing can be more important to a civilised and caring society than children’s physical well-being - hungry children cannot learn anything at all.

In a balanced and caring society in which there is time to sing, to tell stories, and to enjoy family life without grinding hardship, music has its own role to play. People feel more inclined to engage socially and to look out for each other when they feel safe. From this perspective, is music important or not? When people need food to survive, food is more important than music. If people want to build a balanced and cohesive community, both music and food are fundamental for establishing trust and strong relationships whether in family life, business and trade, or diplomacy.

How do we know that music is important for child development?

According to decades of research, infants are exposed to music every day, particularly as their caregivers sing to them to entertain, to soothe and to share emotions with them. Even in utero, at 35 weeks gestational age, foetuses show more movement to musical sounds than to speech sounds, whereas at two months of age, an infant coordinates their gaze with the ‘beat’ of their caregiver’s singing. It is clear that music captures their attention and in this post I’ll point out how it seems to further their development.

What is infant-directed singing?

Infant-directed singing (compared with singing in general) is characterised by a slower tempo, more regularity in the pulse and a relatively wide range in terms of louder and quieter volume. The features of live infant-directed singing include positive emotional expression, accompanied by gestures and facial animation. In play songs there are also actions such as bouncing, jigging or sudden playful movements, whereas slower calming rocking movements characterise the soothing nature of lullabies.

How do infants respond to infant-directed singing?

As infants develop, they begin to adapt their rhythmic movements to coordinate with the rhythmic structure of music that they listen to, but the reasons for this are not well-understood. In terms of language development, years of research on infant listening has indicated that infants are sensitive to the rhythm, volume fluctuations and comprehensibility of speech, including sensitivity to these in nursery rhymes. Recent findings showed that newborn infants’ ability to track fluctuations in singing predicted their expressive language at 18 months.

What is the mechanism?

Researchers have found that these early life experiences of infant-directed singing endow children with sensitivity to the tempo (pace), changes in melodic patterns, harmony and rhythmic patterns of musical extracts. There’s been a recent focus on whether fluctuations in volume map directly onto the listening child’s brain activity, and most recently the same approach has been investigated in listening infants. The researchers refer to the term ‘neural tracking’ and by this they mean the extent to which brain activity is synchronised (entrained) with the features of the singing.

Who took part?

The research involved two different groups of mothers who had expressed an interest in taking part in this research. These mothers aged between 29-39 years, were highly educated: more than 86 per cent of them held university degrees and more than half of them (55 per cent) played a musical instrument, whereas one fifth (20 per cent) had time for themselves and sang in a choir. The authors did not explain the working status of these women, and the amount of time they each spent with their infant, whether some of the infants were enrolled in a crêche, or whether the mothers had chosen to return to work.

During the initial part of the research, all of the infants were seven months of age, lived in German speaking households and were without developmental delay. Across the two groups of participants, nine infants in total were excluded from taking part because of ‘infant fussiness’. This is a common practice in experiments of this kind; this means that the findings reflected the behaviour of infants who were well-adjusted enough to cope with the research protocols (such as wearing an EEG bonnet). The research involved testing the infants’ responses to play songs and lullabies at seven months of age. Then at twenty months, the researchers collected data detailing the children’s expressive language development.

In psychological research, it is important to justify the sample because the characteristics of these individuals are likely to shape the findings to a large extent. It is very difficult to draw broad conclusions about the relevance of infant-directed singing to vocabulary development from this particular group of people, when it is well known that parents’ educational level is a strong predictor of expressive language development in young children (Hart and Risley, 1995).

What is the vocabulary gap?

Expressive vocabulary development and the vocabulary gap became very topical almost thirty years ago when Hart and Risley (1995) conducted their work on vocabulary development in different social groups in America. This groundbreaking study involved analysing 1,300 hours of observations. An average child in a wealthier family heard 2,000 words during an hour, whereas a child from a family receiving welfare, heard 600 words in one hour. By the age of three, children from wealthier backgrounds had twice as many words in their productive vocabulary.

The wider impact of the Hart and Risley research

This finding had a powerful impact and the UK government launched the Sure Start initiative in 1998. Funding became available to enrich the lives of new parents through antenatal classes, postnatal support, parenting courses, nutritional advice, and provided supportive opportunities for very young children living in the poorest neighbourhoods in the UK up to the age of four. This scheme was successful in terms of physical health outcomes; it reduced harsh parenting practices and hospitalisations among children at age eleven. Sure Start Centres lost two thirds of their funding in 2010 and a relatively small number of these centres serve deprived communities.

Will we continue to see malnourished children in 2024?

Unlike Sure Start Centres, which were run in dedicated buildings, the baby banks are grassroots projects and some are set up as a series of tents in deprived rural areas. In the article by Chlöe Hamilton, mothers, who seek help from baby banks cannot afford to heat their homes and feed their children. Moreover, these mothers opt not to feed themselves, even though they are pregnant.

It is in these rural areas that head teachers are very concerned about rising levels of malnourishment. The are seeing children’s teeth falling out, their pupils have bowed legs and stunted physical growth. In some schools, as many as half of the pupils receive free school meals and a free breakfast, which is supplied by the charity ‘Magic Breakfast’. School leaders are also very concerned about children who do not qualify for free school meals, as the lunch they bring to school contains nothing more than cheap sugary snacks.

It is poignant that the first baby bank was started shortly after the banking crisis in 2008. Now there are 200 banks in the UK and over fifty branches are run by one charity, ‘Baby Basics’. According to a London-based charity, ‘Little Village’ twelve per cent of parents needed to visit the baby banks for children’s clothes and toys in the run up to Christmas, 2023.

It is not possible for children to learn when they are hungry and stressed. The lessons of Sure Start apply here. Jessica Murray’s article highlighted how hunger leads to dysfunction in the family relationships and the consequences of this are far reaching according to Dr Sarah Hanson, Associate Professor in Community Health at University of East Anglia:

“There’s evidence that not getting enough to eat causes low mood and anxiety, and often leads to stricter discipline in households. For children, their behaviour worsens and it has been linked to increased asthma diagnoses, as well as significantly higher use of emergency care.”

How is the study on infant-directed singing relevant to this situation?

Although the findings of the infant-directed singing study are more relevant to families of similar social characteristics to the participants: German speaking and highly educated, the most important finding is that infants are listening to their caregivers.

Most interesting perhaps, was that when the researchers manipulated the acoustic features of the singing - the pitch, the tempo, the beat - there was no significant effect on the infants’ neural tracking and this finding is a very inclusive one - infants listen, no matter how strange the singing may sound.

In both lullabies and playsongs, researchers found that infants’ rhythmic movement during the singing was strongly related to their neural tracking. This association between rhythmic movement and neural tracking was statistically significant. Lullabies were notable because they elicited stronger neural tracking - but that is not surprising, given that lullabies are hypnotic by their nature.

The researchers also found that infants’ neural tracking of play songs at seven months was significantly related to their expressive vocabulary at twenty months. This was not a product of chance, (95 percent confidence level). By seven months, these children had already developed playful interactions (involving infant-directed singing and rhythmic movement) in a way that was priming them for productive language. This chimes with the Hart and Risley research and really illustrates the importance of a supportive environment, particularly in the earliest months of an infant’s life.

If your enjoyed this post, keep reading!

Conversations, rhythmic awareness and the attainment gap

In their highly influential study of vocabulary development in the early years, Hart and Risley (1995) showed that parents in professional careers spoke 32 million more words to their children than did parents on welfare, accounting for the vocabulary and language gap at age 3 and the maths gap at age 10 between the children from different home backgrounds.

https://rhythmforreading.com/a/blog/entry/conversations-rhythmic-awareness-and-the-attainment-gap

Narrowing the attainment gap through early reading intervention

Wearing my SENCO hat, I strongly believe that the principle of early reading intervention (as opposed to waiting to see whether a learning difficulty will ‘resolve itself’ over time), and a proactive approach, can narrow the gaps that undeniably exist when children enter primary school.

In 2013, I adapted the Rhythm for Reading programme so that I could put in place urgently needed support for a group of Year 1 and Year 2 children, who struggled with their school’s phonics early reading programme. Their school had already seen impact of the programme on key stage two children, so the leadership team were keen to extend its reach.

The backdrop to reading is the space in the child’s mind.

In a recent post, I referred to Ratner and Bruner’s (1977) article on ‘disappearing’ games such as peekaboo. The article is clear that play of this type contributes to an infant’s ability to engage and interact not only with the game, but with the world around them as well. The playful and even joyful energy of peekaboo accompanies each of these four stages of learning

Gamification, Social Exchange and the Acquisition of Language

According to neuroscientists, repeated use of specific neural pathways catalyses the maturity of the neural structures through a process known as myelination. Referring back to Ratner and Bruner’s question about the ‘nature’ of early ‘disappearing’ games, it appears that language learning during infancy and early childhood coincides with spontaneous and joyful social interaction with an accompanying sense of intrinsic reward. This arguably contributes to successful social interaction throughout life.

References

Hamilton, C., ‘A day at the baby bank: ”I feel at ease here, because I’m not the only one struggling”, The Guardian Newspaper, published on 19.12.23 accessed 30.12.23

Hart, B. And Risley, T.R. (1995) Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children, Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Murray, J, ’Children have bowed legs’: hunger worse than ever, says Norwich School, The Guardian Newspaper, published 21.12.23 accessed 30.12.23

Nguyen et al (2023) Sing to Me Baby: Infants show neural tracking and rhythmic movements to live and dynamic maternal singing, Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 64, 101313

Is learning to read music difficult?

6 December 2023

Some of the most sublime music is remarkably simple to read. Just as the balance of three simple ingredients can make your taste buds ‘pop’, a few notes organised in a particular way can become iconic themes. The opening of Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ and the beginning of the ‘Eastenders’ theme by Simon May are examples of this - as is ‘Jingle Bells’ - (as we are now in December). The point I want to make is that music, like nature, requires balance if it is to feel and sound good. We humans are part of the natural world and our music - varied as it is - is an important part of our natural expression. By this I mean that like other species, we use our voices to attract, bond with, (or repel) each other, socially. In the past two thousand years, music has been written to represent the full range of our social behaviours: from the battleground to the banqueting hall, from the wedding to the funeral, the shop floor to the dance floor, the gym to the sanctuary. We use music to regulate our emotions, to develop our stamina and to motivate ourselves as social groups which behave in particular ways.

We don’t need to read music to enjoy singing with friends at a party or to chant with fans at a sports stadium or to create our own music in the quiet of our own homes. However, if we want to share our own process of creating or performing music, we need to notate it (to write it down) so that we are literally ‘on the same page’ and therefore are able to collaborate more efficiently.

Can you learn to read music without an instrument?

It is very easy to learn to read music ‘without an instrument’ because our voice is our natural instrument. It is also possible to imagine a sound - in the same way that one can imagine a colour or a shape. Musicians can ‘read’ a sheet of music and use the ‘inner ear’ to hear the sounds. When we read a book, our inner voice reads the words in a similar way.

A debate raged for a long time in music education around the idea of ‘sound before symbol’. Some people believed that children were a ‘blank slate’ and needed to learn musical ‘sounds’ before they saw musical symbols in notated form. Others argued that children knew songs before they even started school, and could a manage a more demanding approach such as, ‘sound with symbol’. Fortunately, the era in which ‘sound before symbol’ dominated is now over and teachers can teach musical notation without being regarded as deviant or backward looking. Expensive musical instruments are not necessary for learning to read music. Each child’s voice is a priceless musical instrument, and every child can benefit by developing its use.

Music for health and well-being

Humans have been using music for self-expression for thousands of years. It has been used by people to manipulate perceptions of potential competitors or predators. In situations where people have felt threatened, singing together has helped them to feel strong and brave. Sea shanties are an example of this and in traditional societies people sing through the night to make themselves appear ‘larger’ to predatory animals. To regulate and balance the nervous system, people all around the world soothe themselves through music when they are dealing with grief, using elegies, dirges and laments. When parents comfort infants and young children they sing lullabies to them and also provide a rocking motion, which can ‘lull’ them to sleep.

The human voice can signal alarm through a blood-curdling scream, but it can also provide comfort through well chosen words. Musical expression mirrors this wide range of functions, but it goes much further than language by making use of the exhaling breath. Manipulating the slow exhale, humans have discovered how to shape the voice into elaborate patterns. We can hear this particularly in gospel and operatic traditions - where the feel of improvisation involves an outpouring of emotion. Is it possible to notate these beautiful elaborations? Yes they can be transcribed, but their beauty lies in their spontaneity and the feeling that they emerged from an impulse in a moment of inspiration.

Why do some people struggle to read music?

This is a great question. Given that I’m arguing for music as the natural ‘song’ of our species, why would this natural behaviour flow more easily through some people than others?

Reading as a skill is quite a recent addition to our repertoire of social behaviours. Music and language are natural to us and are ‘hard-wired’ into our nervous system, whereas reading is not - but we are able to learn to read. This skill is well-practised as humans have been using various signs and symbols to communicate for tens of thousands of years.

The main difference between reading music and reading words is that the rhythmic patterns in music are relatively inflexible, whereas printed language is rhythmically malleable. A three word phrase in a printed conversation, such as, ‘I don’t know’ can be reinterpreted by adapting the rhythmic qualities to convey a full range of emotions from exasperation to mystification. When we read, we are guide by the context of the passage. The context would help the reader to identify the most appropriate rhythm for the words. In this respect, rhythm in language reflects context as much as it does the underlying grammatical structure of the sentence.

When reading music, the prescribed rhythmic element reflects the musical context and style. A march, a samba and a ballad each have their own distinctive rhythmic feel. Repeated patterns need to be rhythmically consistent to sound ‘catchy’ or convincing. In this way, rhythm is the stylised and ritualised aspect of music and it can even be hypnotic. This quality in rhythm is the reason it is used by people as a motivational tool, or for self-regulation when the nervous system feels dysregulated.

When reading music, some people struggle to process the rhythmic element. The same people may struggle to move in time with the beat, but this is certainly not an insurmountable problem. It is a question of placing an emphasis on feeling the rhythm first, and then reading the rhythm, once the feeling has been established. This is not always easy because people sometimes feel anxious and believe that they are not ‘rhythmical’ enough.

Children who struggle to read printed language, have learned to read simple musical notation with ease and have responded very well to the Rhythm for Reading Programme. There is a remarkable shift in these children when they realise that by reading musical notation as a group, and through a very profound experience of well-being, belonging and togetherness that this brings, their reading fluency and comprehension also improve.

Our very simple introduction to musical notation involves:

- working with music that is rhythmically balanced,

- an atmosphere that is informal,

- music-making that is joyful.

How to long should it take to learn to read music?

It takes only a few minutes to learn to read simple musical notation. Even children with very weak language reading skills can achieve fluent reading of musical notation in only ten minutes. We focus on integrating each sensory aspect of reading music: the children’s eyes, ears and voices. Children are able to bring their attention into sharper focus when they read musical notation because the rhythmical element, which for them represents emotional safety, has been addressed through our highly structured approach.

If you have enjoyed reading about musical notation…

Click the red button at the top of this page to receive weekly updates from me every Friday.

Discover more about the impact of Rhythm for Reading on children’s reading development in these Case Studies

These posts are also about musical notation

A Simple View of Reading Musical Notation Here are some very traditional views on teaching musical notation - and the Rhythm for Reading way which avoids loading the children with too much information at once.

Fluency, Phonics and Musical Notes Presenting the sound with the symbol is as important in learning to read musical notation, as it is in phoneme-to-grapheme correspondence. Fluent reading for all children is the main teaching goal.

Musical notation, full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection Discover the back story…the very beginning of Rhythm for Reading - this approach was first developed to support children with weak executive function.

Empowering children to read musical notation fluently The ‘tried and tested’ method of adapting musical notation for children who struggle to process information is astonishingly, to add more markings to the page. Rhythm for Reading offers a simple solution that allows all children to read ‘the dots’ fluently, even in the first ten minute session.

A simple view of reading (SVR) musical notation

18 October 2023

Many people think that reading musical notation is difficult. To be fair, many methods of teaching musical notation over-complicate an incredibly simple system. It’s not surprising that so many people believe musical notes are relics of the past and are happy to let them go - but isn’t this like saying books are out of date and that reading literature is antiquated? In homes all around the world, parents of all nationalities can teach children as young as three to read musical notation, as this has for a very long time, become an internationally standardised system. In many schools in all parts of the UK, I’ve taught children at risk of failing the phonics screening check to read simple musical notation fluently in ten minutes. There are distinct differences in my approach and I’m sharing these here.

What is musical notation?

Musicians refer to musical notation as ‘the dots’!

These little marks written on five lines show musicians not only the musical details, but also the bigger picture - they can see the character and the style of the music by the way ’the dots’ are grouped together. Imagine you are looking at a map of your local area - you’d be able to see where buildings and streets are more densely or sparsely grouped together.

This is the skill that musicians use when they look at a page of music - it’s simply a convention for mapping musical sounds.

When was the first music written down?

Early evidence of this practice of notating music can be traced back to its archaic roots in Homer (8th century B.C.E.) Terpander of Lesbos (c. 675 B.C.E.) and Pindar (5th century B.C.E.). However, following the fall of Athens in the 5th century B.C.E., there was a break with tradition. Aristoxenus (c.320 B.C.E..) documented the cultural revolution that had taken place - the rejection of all traditional classical forms. Traditional music had been replaced by -

- a preference for sound effects imitating nature

- free improvisation

- a new fashion for lavishly embellished singing

The rejection of the old ways, including the ‘old music’ appeared to allow space for a new level of freedom. The new emphasis on individual expression rejected:

- traditional tuning systems and forms of both music and poetry

- being part of something greater than oneself

- creating something that would endure.

Musical notation, as the history shows, is less related to individual expression and more to the concept of building a musical canon - a collection of forms, styles and conventions, which are best represented in certain iconic ‘classical’ works. As such, there’s an emphasis on a standardisation of musical language, one that is mathematically well-proportioned, enduring and able to be passed on from generation to generation.

The most ancient system of musical notation, ‘neumes’ in ‘sacred western music’ was used between the 8th and 14th centuries, (C.E.) and was built upon Greek terminology. Most interestingly, the use of the apostrophe /‘/ ‘aspirate’ in the ‘neumes’ survives in today’s musical notation and shows when a musician takes a new breath or makes a slight pause. Part of the standardisation of musical notation has been that it is written on five lines.

What are the five lines called?

These lines, called ‘the stave’, show musicians whether the sounds are higher or lower in frequency (pitch). To take an extreme example, the squeak of a mouse is a high frequency sound (high pitch), and to show this frequency, the dots would be written far above the stave. Conversely, the rumble of a lorry has a low frequency sound (low pitch); to map this sound accurately, the dots would be written far below the stave. Extending the stave in this way involves writing what musicians call ‘ledger lines’.

In a central position within the spectrum of these very high and very low pitched frequencies, we have the pitch range of the human voice. Consider the sounds of the lowest male voice and the highest female voice and it’s clear that the spectrum of frequencies is still very wide. To accommodate this broad range of sounds, musicians write a different ‘clef’ sign at the extreme left of the stave. There are four ‘clef’ signs in common use: the treble (named after the unbroken boys’ voice), alto, tenor and the bass; these clefs are used by singers and instrumentalists alike. The two most commonly used are the bass and treble clefs.

- The bass clef indicates that the pitch range is suited to lower frequency sounds, matching the range of broken male voices.

- The treble clef at the extreme left of the stave indicates that the pitch range matches that of children’s and female voices.

What is the line between the notes called?

In the early 1600s, for reasons of clearer musical organisation, vertical lines started to appear in notation, which divided the music into ‘bars’ (UK) or ‘measures’ (US). For the most part, the number of beats is standardised in each bar. Keep reading to find out more about the beats!

Many of the most catchy pieces of Western music rely on simple repetition of short patterns as well as predictable beats. We perceive these to fall naturally into a regular grouping, and most melodies fall into a pattern of two, three or four beats, spread across the piece or song. Here are two recognisable examples, the first in three time, the second in four time:

- God save the King (UK) or God Bless America (US)

- Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.

Of course, we all know music that’s more complex than this. For example, traditional dance styles from all around the world are often more elaborate and combine rhythmic groupings of faster-paced patterns such as:

- 2s with 3s

- 4s with 3s

- 4s with 5s

Although these occasionally appeared in iconic classical works of the 19th century such as Mussorgsky’s ‘Pictures at an Exhibition,’ and Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, they became more commonplace in the early 20th century. These slightly irregular groupings create subtle feelings of asymmetry that is as delightful to the ear as new taste sensations are to the palette.

If there are five beats, as in ‘Take Five’ by Dave Brubeck, then after each group of five beats a vertical line shows the end of the ‘measure’ (US) also known as the ‘barline’ (UK). The bars or measures are units of time that show the organisation of the beats in the music.

Generally, ‘the dots’ and rhythms show the structure of a piece, or how it ‘works’ musically. In performance, a musician would maintain a consistent rhythmic ‘feel’. So these two essential notational elements offer a framework of predictability, which the musician reads, understands and feels:

- the number of beats in each bar

- the grouping and rhythm of the beats and notes within these bars

However, too much emphasis on the predictability and the vertical organisation of the beats can produce an effect that is wooden and robotic. Although a strict sense of rhythm and pulse (the beat) is essential for successful music making, the actual phrasing of these is more horizontal and somewhat elastic in feel.

This can work by making more of the musical tension, by stretching it in time and intensity, as well as making it louder and moving forward; it can help the listener wait in anticipation for the all-important climax and moment of release. This is incredibly effective at all levels of music making, and is known to us all in the more familiar context of telling jokes and stories, where the pacing is as important as the details.

So, this is why experienced musicians use ‘the dots’ only as a map, and allow their ‘feel’ for the rhythm, the harmony and the style to bring freedom and individuality to their expression.

What are ‘heads’ and ‘stems’?

The anatomy of ‘the dots’ tells musicians about the pitch and the time values of sounds they make.

The ‘heads’ are the oval shaped part of a note, whereas the ‘stem’ is the line that may be attached to the ‘head’. The ‘head’ of the note moves around on the stave and tells the musician about pitch and depending on whether it’s filled (black) or open (white), about time value. The ‘stem’ of the note can join with other ‘stems’ (called ‘beaming’) and tells the musician about time and emphasis.

Some teachers of musical notation are very ‘head’ focussed and have elaborate mnemonics for memorising the positions of ‘the dots’ on the stave. Here are some examples:

- All Cows Eat Grass (the spaces of the bass clef - A,C,E,G)

- Good Boys Deserve Fun Always (the lines of the bass clef - G,B,D,F,A)

- FACE (the spaces of the treble clef - F,A,C,E)

- Every Good Boy Deserves Food (the lines of the table clef - E,G,B,D,F)

The major problem with this approach is that it involves cognitive loading, as remembering these patterns rapidly absorbs a child’s finite cognitive resources. As a prerequisite for learning to read notation, these mnemonic patterns must be memorised and then applied in real time. Although this approach is not difficult for pupils with a strong working memory, it is absolutely why reading musical notation has gained its reputation for being ‘too difficult’ for some children to engage with.

Some leading musical education programmes in use today, are very ‘stem’ focussed and have elaborate time names for longer and shorter durations: ‘ta’ ‘ti-ti’ ‘tiri-tiri’ and ‘too’. Or, ‘Ta-ah’ ‘Ta’ ‘Ta-Te’ ‘Tafa-Tefe’ and there are many more to choose from.

The issue here is that the sound names are confusable because they sound so similar. Children with specific learning difficulties are likely to conflate these, and experience rhythm as confusing. This is unnecessary and easily avoided. Furthermore, it places children with weak working memory and weak sensitivity to phonemes at a considerable disadvantage.

We have completely avoided these issues in Rhythm for Reading and have opted for something simpler that does not front-load children’s attentional resources. In addition, our approach allows reading fluency to develop in the very first session.

We use simple and familiar language. ‘The dots’ are compared with lollipops and described as ‘blobs’ and ‘sticks’. Time names ‘ta’ and ‘ti-ti’ are simplified as ‘long’ and ‘quick quick’. There’s no confusion. This allows us to get on with the business of reading - fluently.

We offer professional development (CPD) that is deeply rooted in neuroscience, the development of executive function and of course, cognitive load theory. You can find out more in the following links.

Fluency, phonics and musical notes: Presenting the sound with the symbol is as important in learning to read musical notation, as it is in phoneme-grapheme correspondence. Fluent reading for all children is our main teaching goal.

Musical notation, full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection: Discover the back story… the beginning of Rhythm for Reading - an approach that was first developed to support children with weak executive control.

Empowering children to read music fluently: The ‘tried and tested’ method of adapting musical notation for children who struggle to process information is astonishingly, to add more markings to the page. Rhythm for Reading offers a simple solution that allows all children to read ‘the dots’ fluently, even in the first ten minute session.

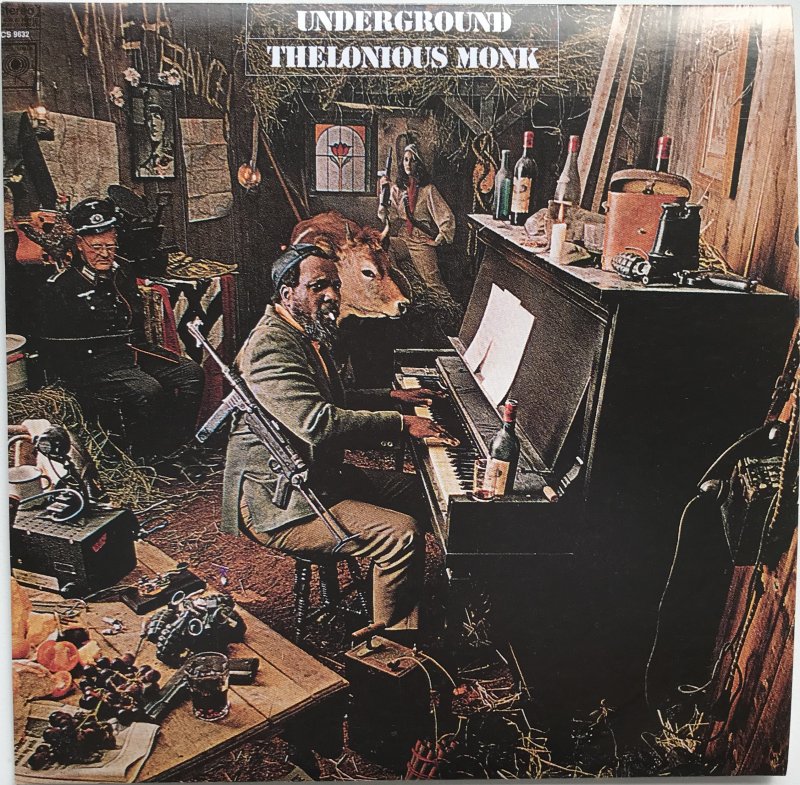

Thelonius Monk (1917-1982) A personal tribute

4 October 2023

Black History Month invites us to celebrate our differences more than ever. A knowledge-rich curriculum offers big ideas and invaluable depth of insight, but the creativity of Monk shows how knowledge can be developed to pioneer new forms and techniques. His music is unmatched in its capacity to inspire people of all ages because of its originality, which is preserved in the recordings. We are very fortunate indeed to be able to hear the playing and ideas of a musician who has led the development of an entire genre.

Having been hugely inspired by Thelonius Monk’s music, artistry and originality, I am going to express my appreciation for this exquisite musician here even though it’s impossible to do full justice to this musical icon through words alone. As a musician he is one of a kind - therefore this blog post will fall spectacularly short. But, as there is a huge gap between the struggles he endured during his lifetime and the huge amount of recognition that his artistry and humanity has received since his death, I’m going to highlight these contrasts here.

Back in the day…having graduated from the Royal Academy of Music in the late 1980s I was working with the superb musician, innovative pianist and inspirational composer, Roger Eno. I remember asking him about the artists he most deeply admired. Hearing Eno talking about Monk was so moving that I rushed out to buy a couple of albums - later that same day I listened closely to this giant of jazz.

A musician’s musician

Monk is truly a musicians’ musician. He inspires us to dig deeper and think bigger, to create with true integrity and honesty. There are forty-nine tribute albums made by admiring colleagues dating from 1958 right up to present times - the most recent was recorded in 2020. Posthumously, Monk has been awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1993), and the Pulitzer Prize (2006), but it wasn’t until 2009 that he was honoured by his home state in the North Carolina ‘Hall of Fame’.

My own first impressions, hearing this genius for the first time were a mixture of the deepest gratitude for his sincerity, and delighted astonishment in his freedom, playfulness and wit. There are other musicians who can match Monk’s dazzling piano technique - but what sets Monk apart for me, is that he took his mastery of the piano to a level of creativity that was utterly original.

Tenderness, wit and subversion

He used the piano to acknowledge tenderness, to dismantle and reweave others’ works and he delightfully subverted iconic works by other composers.Take for example, ‘Criss-Cross’ - in this track, Monk mocks Stravinsky’s ballet, ‘The Rite of Spring’ and we hear the saxophone and the piano calling out the famous opening motif played by the solo bassoon. Later Stravinsky’s ‘primal’ cross rhythms emerge through the composition, repurposed by Monk to restore percussive vibrancy to the nuanced rhythmic feel of these patterns.

Even more vivid perhaps, is ‘North of Sunset’. This track nods to the traditional blues which appear and disappear fleetingly, like shadowy outcasts in the glare of Monk’s quirky grammatical purity and the lean contours of his modern jazz style.

Architecture and musical form

Then there’s Monk’s relationship with depth and perspective. The best musical compositions of any genre have an architectural quality, with clearly defined form and proportions unfolding through sound. And yet in Monk we hear musical structures projected with the clarity of a hologram. For instance in the track, ‘Between the devil and the deep blue sea’ (based on Harold Arlen’s work of 1931) there’s infinite perfection in the proportions. Monk matches structural precision with a vivid portrayal of the title. At the end of his solo, he pushes the music over the edge and into vertiginous cascades of notes, shaking up our depth perception. Then there’s a curious restlessness that smoulders and smokes, depicting the title of the track perfectly.

Mimicry and magic

Other tracks that come to mind with a similarly dazzling precision are ‘Locomotive’ in which the breadth of the ‘groove’ evokes a driving mechanical feel, punctuated by crunchy chordal edginess. ‘Tea for Two’ is joyful in a suitably restrained and respectful way, but then unexpectedly explodes into a delightful sound world, mimicking the clatter of porcelain teacups and saucers. Elsewhere there are fleeting references to Schubert’s ‘Trout’ Quintet, with Monk conjuring witty and magical surprises.

Contemplative mood

It’s not all about wit and clever jokes. One of the things I most admire most about Monk as a performing artist is his use of space and silence. In ‘Japanese Folk Song’ the lyrical melody is stripped back to an emaciated dry skeleton, devoid of unnecessary or extra sounds and yet this transformation makes it all the more potent. Sharing with us the nakedness of the folk song, he displays his extraordinary gift for working with the essence of melody and the spaces between notes - in this case the chasms between chords, which achieve alchemy in real time.

In these tracks he shows his powers in dismantling a melody, a musical style, and a genre, then rebuilding it, but with the precision of a watchmaker whose fingers were immediately able to align the sound with whatever his mind envisioned.

Creativity flowing from ambiguous moments

After my own thoroughly classical training, encountering the exuberance of his playing reminded me what music was really for and how our creativity is the most authentic gift humans can offer to one other. For an illustration of this, in ‘We See,’ the abrupt musical fissures in the seemingly conventional introduction metamorphose into an extraordinary spaciousness. We soon discover that this ambiguity is the precursor, the necessary foundation from which a richer harmonic language emerges. Complementing the depth and complexity of the harmonies, we hear Monk’s ability to stretch and mould the elasticity of cross-rhythms and lilting flexibility of the phrases. Monk was always searching for the edges of extremes within the logic of balance, but in this track he appears to explore the boundaries of what’s possible in a more playful and yet still profound way.

Necessity as the mother of invention

When researching this post, I was sad to read about his struggles in life. He had even endured being beaten and unlawfully detained by the police. In every setback he displayed resilience and dignity. Surely the sophistication of his playing developed in part from sheer necessity: he had to create this unique style so that his music became his intellectual property - it was essentially impossible to copy. Listening to the melody in Monk’s ‘Bolivar Blues’ however, the ‘hit’ theme song ‘Cruella De Vil’ from Disney’s ‘1001 Dalmatians’ clearly shows more than a ‘homage’ to Monk. And he didn’t receive the full recognition that he deserved during his lifetime. Had Monk been awarded the Grammy and the Pulitzer while still alive, I would like to think that he’d have played more in the later years of his life and suffered fewer mental health issues.

Outcast or Genius?

Just as most books about reading development don’t mention rhythm, books about music tend not to mention Monk. But, Steven Pinker in ‘How the Mind Works’, is unequivocal under the heading ‘Eureka!’

And what about the genius? How can natural selection explain a Shakespeare, a Mozart, an Einstein, an Abdul-Jabbar? How would Jane Austen, Vincent van Gogh, or Thelonius Monk have earned their keep on the Pleistocene savannah?

Here’s part of Pinker’s brilliant answer to his own question:

But creative geniuses are distinguished not just by their extraordinary works, but by their extraordinary way of working; they are not supposed to think like you and me.

If you enjoyed reading about this giant of jazz, here are links to related posts about the value of music and creative subjects in the curriculum - (with a light touch of political opinion). As Brian Sutton-Smith once said,

The opposite of play is not work. The opposite of play is depression.

Creativity, constraints and accountability - Creativity is hardwired within all of us and there’s a playfulness in the ‘what if…’ process which guides an unfolding of impulse, logic and design.

The Power of Music – This post discusses Professor Sue Hallam’s ‘Power of Music’ - a document that reviews more than 600 scholarly publications on the effect of music on literacy, numeracy, personal and social skills to support the need for of music in the education of every child.

Knowledge, culture and control - Is history cyclical? As we move rapidly into climate crisis, artificial intelligence (AI) and a school curriculum dominated by STEM subjects, this post questions the present lack of emphasis on critical thinking and creativity.

Musical notation, a full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection

10 January 2023Many years ago, I was asked to teach a group of children, nine and ten years of age to play the cello. To begin with, I taught them to play well known songs by ear until they had developed a solid technique. They had free school meals, which in those days entitled them access to free group music lessons and musical instruments. One day, I announced that we were going to learn to read musical notation. The colour drained from their faces. They were agitated, anxious and horrified by this idea.

No! they protested. It’s too hard.

After all these lessons, do you really think I would allow you to struggle? I asked them.

The following week, I introduced the group to very simple notation and developed a system that would allow them to retain the name of each note with ease, promoting reading fluency right from the start. This system is now an integral part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. It was first developed for these children, who according to their class teacher, were unable either to focus their attention or to learn along with the rest of the class.

After only five minutes, the children were delighted to discover that reading musical notation was not so difficult after all.

I can do it! shrieked the most excitable child again and again, and there was a wonderful atmosphere of triumph in the room that day.

After six months, the entire group had developed a repertoire of pieces that they could play together as a group and as individuals. It was at this point that Ofsted inspected the school. The Headteacher invited the children to play in full school assembly in the presence of the Ofsted inspection team. They played both as a group and as soloists. Each child announced the title and composer of their chosen piece, played impeccably, took applause by bowing, and then walked with their instrument to the side of the hall. At the end of the assembly the children (who were now working at age expectation in the classroom) were invited to join the school orchestra and sit alongside their more privileged peers. The Ofsted team placed the school in the top category, ‘Outstanding’.

If you would like to learn more about this reading programme, contact me here.

Rhythm, phonemes, fluency and luggage

12 December 2022

Louis Vuitton began his career in logistics and packing, before moving on to design a system of beautiful trunks, cases and bags that utilised space efficiently and eased the flow of luggage during transit. He protected his designer luggage using a logo and geometric motifs. The dimensions of each piece differed in terms of shape and size, and yet it was undeniable that they all belonged together as a set - not only because they matched in appearance, but also because each piece of the set could be contained within a larger piece. In fact, the entire set was designed to fit into the largest piece of all.

The grammatical structures of language and music share this same principle that underpinned the Louis Vuitton concept. In a language utterance, the tone, the pace and the shape of the sound waves carry a message at every level - from the smallest phoneme to the trajectory of the entire sentence.

The shapes of individual syllables are contained within the shapes of words. The shapes of words are contained within the shapes of phrases and sentences. Although these are constantly changing in real time - like a kaleidoscope, the principle of hierarchy - a single unit that fits perfectly within another remains robust.

In music, the shapes of riffs, licks, motifs, melodies and phrases are highly varied, but the hierarchical principle remains a constant here too. The musical message is heard in the tone, the pace and the shape of the smallest and largest units of a musical phrase.

Just as Vuitton used design to create accurate dimensions at every level of his luggage set, the same degree of precision is also achieved at a subconscious level in spoken language and in music. A protruding syllable, the wrong emphasis or inflection can throw the meaning of an entire sentence out of alignment. A musical message is similarly diluted if a beat protrudes, is cut short or is lengthened, because the length and shape of an entire phrase is distorted.

Arguably, the precise dimensions in Vuitton’s groundbreaking designs reflect a preference for proportion and balance that also underpins human communication involving sound. Our delight in the consummation of symmetry, grammar and rhyme is present in the rhythm of language and also in music. At a conceptual level, it is ratio that unifies the Vuitton designs with language and music, and it is ratio that anchors our human experience in interaction with one another and our environment.

This concept of ratio, as well as hierarchical relationships and the precision of rhythm in real time underpin the Rhythm for Reading programme. Think of this reading intervention as an opportunity to reorganise reading behaviour using a beautiful luggage set, designed for phonemes, syllables, words and phrases. It’s an organisational system that facilitates the development of reading fluency, and also reading with ease, enjoyment and understanding.