The Rhythm for Reading blog

Rhythm and Contribution 4/5

1 October 2018Contribution is a tremendously positive aspect of human nature. At this time of year in many schools, it’s possible to detect a special sense of dignity emerging from a collective sense of contribution. Central to the season of Harvest Festival, contribution is a natural response to our awareness of our of abundance and supply. We pause to appreciate the hard work of the farmers and the benefits of a favourable climate, essential for the long-term sustainability of crops and livestock. It is a time to reflect and give thanks for the magnificent, vibrant beauty of our planet. Sharing the gifts of our abundance with the wider community reminds us that the gift of contribution is also the gift of belonging.

In classrooms, a quite different notion of contribution exists. Students’ contribution in the classroom is evaluated by teachers. Yet at the same time, contribution is restricted by the limited amount of time teachers are able to allocate each unit of work. Tension around contribution in the classroom arises between the need to cover the curriculum and the time students may need to assimilate concepts before they feel ready to reflect and engage via questions or discussion. A possible solution is to allow more time. Expanding the time allowed for students’ contribution seems to slow the whole process of learning down. However, this may be time well spent, particularly for lower attaining students, who may learn differently or simply need more time to process the information, as argued by Rowe, (1986).

Contribution is also a form of social action. In the context of Harvest Festival, there is a sense that everybody contributes what they can, but in a classroom the act of contributing to a curriculum that may or may not seem relevant and relatable can be stressful for some students. Accordingly, ‘children tend to feel vulnerable in school’ (Pollard, 1987, p.4), where they are subject to a process of assessment and rules. Children learn to adapt, to cope with power and discipline of the teacher, to avoid situations that may lead to humiliation or disrespect, particularly in front of peers in the classroom. Seen through this lens, contribution can be complex, troubling for students, and very different to the contribution that takes place in the school hall during a Harvest Festival.

In Rhythm for Reading sessions, contribution is extremely important. Each session lasts only ten minutes in length, so the students need to commit themselves to tasks from the very beginning of the session. Every second is dedicated to contribution. The main difference between students’ contribution in Rhythm for Reading sessions and the classroom is that they contribute simultaneously as a group rather than as individuals. This reduces the sense of vulnerability considerably. The contribution that they make as a group involves consideration of others; for example in the way that they blend their voices together so that no one is louder or quieter than anyone else. This achieves a true sense of group cooperation in which everyone can feel that the energies of contributing and belonging are truly symbiotic.

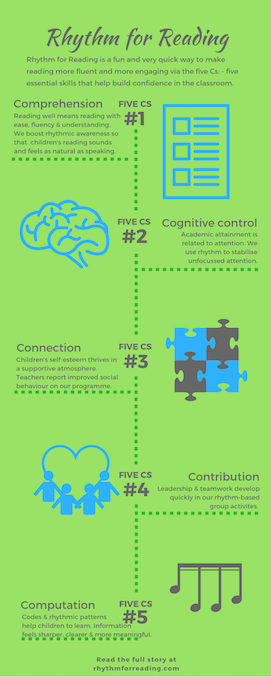

Although the pressures on teachers and students are seemingly increasingly difficult to resolve, Rhythm for Reading by its nature is non-competitive, harmonious and inclusive. As such, it bridges the chasm between the starkly contrasting forms of contribution occurring in the classroom and the school hall. Rhythm for Reading makes use of rhythmic patterns rather than words to develop reading skills, yet builds fluency, cognitive control and confidence, while cementing group cohesion and commitment to learning.

Pollard, A. (1987). Introduction: New Perspectives on Children, In A. Pollard (Ed.) Children and their primary schools: A new perspective, (p. 1- 11), The Falmer Press, taylor & Francis Inc., London, New York & Philadelphia

Rowe, M. (1986). Slowing down may be a way of speeding up! Journal of Teacher Education, 37, 43-50.