A simple view of reading - musical notation

18 October 2023

Many people think that reading musical notation is difficult. To be fair, many methods of teaching musical notation over-complicate an incredibly simple system. It’s not surprising that so many people believe musical notes are relics of the past and are happy to let them go - but isn’t this like saying books are out of date and that reading literature is antiquated? In homes all around the world, parents of all nationalities can teach children as young as three to read musical notation, as this has for a very long time become an internationally standardised system. In many schools in all parts of the UK, I’ve taught children at risk of failing the phonics screening check to read simple musical notation fluently in ten minutes. There are distinct differences in my approach and I’m sharing these here.

What is musical notation?

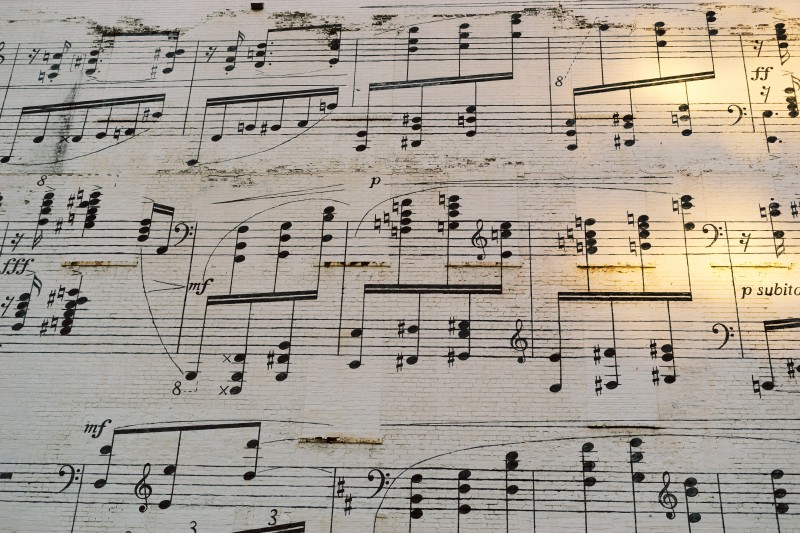

Musicians refer to musical notation as ‘the dots’!

These little marks written on five lines show musicians not only the musical details, but also the bigger picture - they can see the character and the style of the music by the way ’the dots’ are grouped together. Imagine you are looking at a map of your local area - you’d be able to see where buildings and streets are more densely or sparsely grouped together.

This is the skill that musicians use when they look at a page of music - it’s simply a convention for mapping musical sounds.

When was the first music written down?

Early evidence of this practice of notating music can be traced back to its archaic roots in Homer (8th century B.C.E.) Terpander of Lesbos (c. 675 B.C.E.) and Pindar (5th century B.C.E.). However, following the fall of Athens in the 5th century B.C.E., there was a break with tradition. Aristoxenus (c.320 B.C.E..) documented the cultural revolution that had taken place - the rejection of all traditional classical forms. Traditional music had been replaced by -

- a preference for sound effects imitating nature

- free improvisation

- a new fashion for lavishly embellished singing

The rejection of the old ways, including the ‘old music’ appeared to allow space for a new level of freedom. The new emphasis on individual expression rejected:

- traditional tuning systems and forms of both music and poetry

- being part of something greater than oneself

- creating something that would endure.

Musical notation, as the history shows, is less related to individual expression and more to the concept of building a musical canon - a collection of forms, styles and conventions, which are best represented in certain iconic ‘classical’ works. As such, there’s an emphasis on a standardisation of musical language, one that is mathematically well-proportioned, enduring and able to be passed on from generation to generation.

The most ancient system of musical notation, ‘neumes’ in ‘sacred western music’ was used between the 8th and 14th centuries, (C.E.) and was built upon Greek terminology. Most interestingly, the use of the apostrophe /‘/ ‘aspirate’ in the ‘neumes’ survives in today’s musical notation and shows when a musician takes a new breath or makes a slight pause. Part of the standardisation of musical notation has been that it is written on five lines.

What are the five lines called?

These lines, called ‘the stave’, show musicians whether the sounds are higher or lower in frequency (pitch). To take an extreme example, the squeak of a mouse is a high frequency sound (high pitch), and to show this frequency, the dots would be written far above the stave. Conversely, the rumble of a lorry has a low frequency sound (low pitch); to map this sound accurately, the dots would be written far below the stave. Extending the stave in this way involves writing what musicians call ‘ledger lines’.

In a central position within the spectrum of these very high and very low pitched frequencies, we have the pitch range of the human voice. Consider the sounds of the lowest male voice and the highest female voice and it’s clear that the spectrum of frequencies is still very wide. To accommodate this broad range of sounds, musicians write a different ‘clef’ sign at the extreme left of the stave. There are four ‘clef’ signs in common use: the treble (named after the unbroken boys’ voice), alto, tenor and the bass; these clefs are used by singers and instrumentalists alike. The two most commonly used are the bass and treble clefs.

- The bass clef indicates that the pitch range is suited to lower frequency sounds, matching the range of broken male voices.

- The treble clef at the extreme left of the stave indicates that the pitch range matches that of children’s and female voices.

What is the line between the notes called?

In the early 1600s, for reasons of clearer musical organisation, vertical lines started to appear in notation, which divided the music into ‘bars’ (UK) or ‘measures’ (US). For the most part, the number of beats is standardised in each bar. Keep reading to find out more about the beats!

Many of the most catchy pieces of Western music rely on simple repetition of short patterns as well as predictable beats. We perceive these to fall naturally into a regular grouping, and most melodies fall into a pattern of two, three or four beats, spread across the piece or song. Here are two recognisable examples, the first in three time, the second in four time:

- God save the King (UK) or God Bless America (US)

- Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.

Of course, we all know music that’s more complex than this. For example, traditional dance styles from all around the world are often more elaborate and combine rhythmic groupings of faster-paced patterns such as:

- 2s with 3s

- 4s with 3s

- 4s with 5s

Although these occasionally appeared in iconic classical works of the 19th century such as Mussorgsky’s ‘Pictures at an Exhibition,’ and Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, they became more commonplace in the early 20th century. These slightly irregular groupings create subtle feelings of asymmetry that is as delightful to the ear as new taste sensations are to the palette.

If there are five beats, as in ‘Take Five’ by Dave Brubeck, then after each group of five beats a vertical line shows the end of the ‘measure’ (US) also known as the ‘barline’ (UK). The bars or measures are units of time that show the organisation of the beats in the music.

Generally, ‘the dots’ and rhythms show the structure of a piece, or how it ‘works’ musically. In performance, a musician would maintain a consistent rhythmic ‘feel’. So these two essential notational elements offer a framework of predictability, which the musician reads, understands and feels:

- the number of beats in each bar

- the grouping and rhythm of the beats and notes within these bars

However, too much emphasis on the predictability and the vertical organisation of the beats can produce an effect that is wooden and robotic. Although a strict sense of rhythm and pulse (the beat) is essential for successful music making, the actual phrasing of these is more horizontal and somewhat elastic in feel.

This can work by making more of the musical tension, by stretching it in time and intensity, as well as making it louder and moving forward; it can help the listener wait in anticipation for the all-important climax and moment of release. This is incredibly effective at all levels of music making, and is known to us all in the more familiar context of telling jokes and stories, where the pacing is as important as the details.

So, this is why experienced musicians use ‘the dots’ only as a map, and allow their ‘feel’ for the rhythm, the harmony and the style to bring freedom and individuality to their expression.

What are ‘heads’ and ‘stems’?

The anatomy of ‘the dots’ tells musicians about the pitch and the time values of sounds they make.

The ‘heads’ are the oval shaped part of a note, whereas the ‘stem’ is the line that may be attached to the ‘head’. The ‘head’ of the note moves around on the stave and tells the musician about pitch and depending on whether it’s filled (black) or open (white), about time value. The ‘stem’ of the note can join with other ‘stems’ (called ‘beaming’) and tells the musician about time and emphasis.

Some teachers of musical notation are very ‘head’ focussed and have elaborate mnemonics for memorising the positions of ‘the dots’ on the stave. Here are some examples:

- All Cows Eat Grass (the spaces of the bass clef - A,C,E,G)

- Good Boys Deserve Fun Always (the lines of the bass clef - G,B,D,F,A)

- FACE (the spaces of the treble clef - F,A,C,E)

- Every Good Boy Deserves Food (the lines of the table clef - E,G,B,D,F)

The major problem with this approach is that it involves cognitive loading, as remembering these patterns rapidly absorbs a child’s finite cognitive resources. As a prerequisite for learning to read notation, these mnemonic patterns must be memorised and then applied in real time. Although this approach is not difficult for pupils with a strong working memory, it is absolutely why reading musical notation has gained its reputation for being ‘too difficult’ for some children to engage with.

Some leading musical education programmes in use today, are very ‘stem’ focussed and have elaborate time names for longer and shorter durations: ‘ta’ ‘ti-ti’ ‘tiri-tiri’ and ‘too’. Or, ‘Ta-ah’ ‘Ta’ ‘Ta-Te’ ‘Tafa-Tefe’ and there are many more to choose from.

The issue here is that the sound names are confusable because they sound so similar. Children with specific learning difficulties are likely to conflate these, and experience rhythm as confusing. This is unnecessary and easily avoided. Furthermore, it places children with weak working memory and weak sensitivity to phonemes at a considerable disadvantage.

We have completely avoided these issues in Rhythm for Reading and have opted for something simpler that does not front-load children’s attentional resources. In addition, our approach allows reading fluency to develop in the very first session.

We use simple and familiar language. ‘The dots’ are compared with lollipops and described as ‘blobs’ and ‘sticks’. Time names ‘ta’ and ‘ti-ti’ are simplified as ‘long’ and ‘quick quick’. There’s no confusion. This allows us to get on with the business of reading - fluently.

We offer professional development (CPD) that is deeply rooted in neuroscience, the development of executive function and of course, cognitive load theory. You can find out more in the following links.

Fluency, phonics and musical notes: Presenting the sound with the symbol is as important in learning to read musical notation, as it is in phoneme-grapheme correspondence. Fluent reading for all children is our main teaching goal.

Musical notation, full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection: Discover the back story… the beginning of Rhythm for Reading - an approach that was first developed to support children with weak executive control.

Empowering children to read music fluently: The ‘tried and tested’ method of adapting musical notation for children who struggle to process information is astonishingly, to add more markings to the page. Rhythm for Reading offers a simple solution that allows all children to read ‘the dots’ fluently, even in the first ten minute session.

Tags:

Do you have any feedback on this blog post? Email or tweet us.