The Rhythm for Reading blog

All posts tagged 'executive-function'

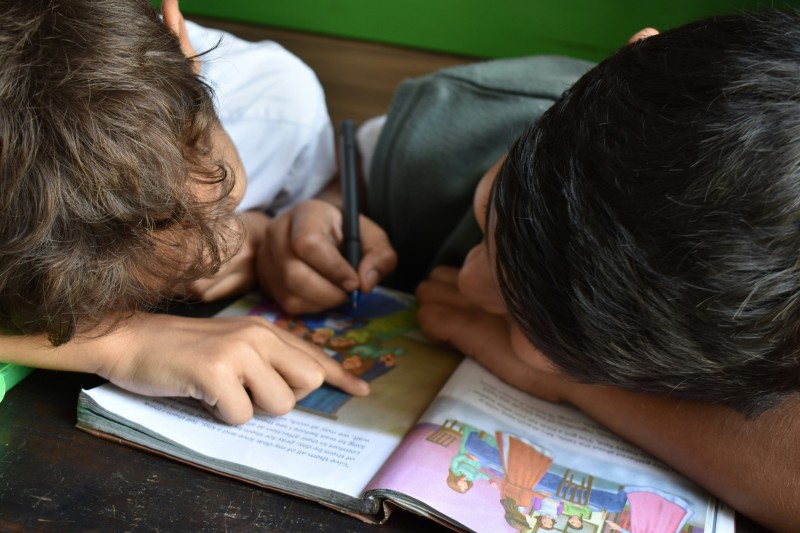

Sharing Stories: Reflections on World Book Day

8 March 2024

Our love of stories, whether fiction or non-fiction creates an appetite for more information. Stories are irresistible to us because they reward our curiosity about others’ experiences. They inspire us and invite us to consider the unimaginable possibilities that exist outside our familiar day-to-day lives.

According to psychologists we are hard-wired to enjoy stories. This is for reasons that are inextricably linked to our survival. Our instincts interpret day-to-day events as stories and the majority of these never reach our conscious awareness; but on the other hand, the most salient moments stand out because they were unusual in some way: it is that that made them memorable.

Narrative and the nervous system

About twenty years ago, I remember riding on a small, rickety electric train. Like most trains, it had seats, mini carriages and wheels, but no sides and no roof. It jolted as it carried us on a miniature railway deep underground. The air became colder and everyone was chattering quietly as we rumbled deep down into the limestone rocks. We were on our way to see prehistoric cave art. In the distance a low murmuring caught my attention. I hoped it might be an underground flow of water, but suddenly our train stopped and the low vibration became louder as it approached us. I had no idea what to expect. The noise was deafening and the lights went out. We sat not only in silence, but in dread.

This is a true story based on the uncertainty that we, the tourists, all experienced in an unfamiliar place, cut off from the outside world and in fear of impending doom! As it turned out the trains always passed each other in this way and the matter of altering the points on the tracks was done manually. Once the lights came back on, and having experienced an immense surge of relief, I think we enjoyed the cave art even more.

Perhaps the drama of the half hour ride into the hillside put us all in touch with the deepest feelings of terror that the nervous system is primed to deliver. There was nowhere to hide during that unusual experience and we all felt vulnerable for about ten minutes. Perhaps it was by design that we experienced what the early artists may have felt when they made the cave art at ‘Grotte de Chauvet’, so far away from the familiarity of mundane life on the surface.

And as today is International Women’s Day, I’d like to acknowledge that the cave art at Chauvet, was most likely made by women. It was executed in red and depicted the female form in relation to sacred animals, as well as handprints of red ochre (Fagan, 2005).

Reflecting on the life ways of ‘Cro Magnon’ man at the end of the Ice Age, Brian Fagan acknowledged the importance of music and stories when he described the challenges of living within the natural world. There were long hard winters and an unpredictable supply of food; but the rhythm of the seasons remained unchanged:

‘People thought of themselves as part of a living world, where animals, plants, and even landmarks and inanimate objects had lives of their own. The environment lived and surrounded one, defined by intangible forces and personalities, whether human or not. To live in such a way required a powerful imagination, the ability to conceptualise, to chant, to make music, and to tell tales that validated human existence and explained the natural order of things.’ (Fagan, 2005, p.142)

However, only a few thousand years later human societies experienced a technological revolution. They harnessed the cyclic seasonal rhythms of nature and through the advent of farming, created a more predictable supply of food. In the transitions from hunter gatherers to farmers, and then into city dwelling civilisations, the functions of storytelling also changed to reflect the new challenges that humans faced. Living in closer proximity, humans experienced profound changes in terms of sanitation and disease.

In his ‘Selfish Gene Theory’, Dawkins (1976) proposed that humans were susceptible to stories, particularly those that involved supernatural powers, (not because our sensibilities were finely attuned to the natural environment throughout our evolution), but because they were gullible and self-delusional. In a similar vein, Humphrey’s ‘Machiavellian Theory’ (1976) acknowledged that as humans became more socially sophisticated, they were better able to deceive and outwit each other. This would involve inferring and anticipating the thoughts of another and also an ability to envision imaginary scenarios. The creation of fiction and story-telling may well have become more important for navigating social structures in the new villages and first cities - anticipating an unpredictable supply of food was no longer society’s primary concern.

Before the first books were written

Before the first books were written, people would share the most iconic stories in verse form or as ballads. The couplets of verse and the regular structures of songs helped with learning and recalling all the details, and this was important for maintaining the integrity and credibility of the narrative with each retelling. The most important information, such as the early laws in Ancient Greece for example, were recited in verse for this reason.

According to Thucydides, the citizens of Ancient Greece were schooled in a rich oral culture through the recitation. These were later written down by Homer as the famous Iliad and Odyssey, which detailed the epic feats of supernatural figures: Greek gods, goddesses, heroes and heroines. The driving metre and melodious quality of the poetry, in particular the rhythmic and repetitive lines, helped the young citizens to commit large amounts of material to memory (Wolf, 2007, p.57). Arguably, the Ancient Greeks had learned to hone and develop executive cognitive functions through these techniques as the benefits of committing large amounts of material to memory included achieving mental focus and control of distraction. Hierarchical structures in the form of the poetry would have supported logical and philosophical thinking as well as provided the ability to ‘step back’ and see the ‘big picture’.

As a side note, today’s professional musicians, dancers and actors in the creative sector’s performing arts are trained through the traditional discipline of each art form to commit large volumes of information to memory for public performances. These are now celebrated and ‘consumed’ via live streaming, broadcasts and recordings, and enjoyed by audiences all around the world.

Prehistory ended when the first story was written down

According to art historian, Zainab Bahrani, the first stories ever recorded were ‘ancient myths of origins’, which dated back to Mesopotamia of the historical era, when higher levels of art and architecture began to emerge. The Mesopotamians credited a god known as ‘Enki’ (Sumarian) and also known as Ea (Akkadian) and this deity was associated with the creative origin of the world.

Similarly, there was a Babylonian myth that described a place called ‘Eridu’. This was thought to be the first place to be created by the gods and ‘Eridu’ was sacred to ‘Enki’, the god of water, wisdom and craftmanship’ ((Bahrani, 2017, p. 42).

‘The city of ‘Eridu’ is recounted here, and even in this early story, translated into English (Bahrani, 2017, p. 36), it is clear that the narrative is presented in a rhythmically coherent way and with a clear structure:

“A holy house, a house of the gods in a holy

place had not been made, reed had not come

forth, a tree had not been created,

A brick had not been laid, a brick mould

had not been built,

A city had not been made, a living creature

had not been placed (within)

All the lands were sea,

The spring in the sea was a water pipe.

The Eridu was made.”

The city of Eridu was discovered in the twentieth century and this work revealed that people had first lived there some seven thousand years ago, and had created no less than eighteen excavated levels of occupation. By studying these levels, academics have been able to map the story of cultural development of this society over many generations, from hunter gatherers, to farmers, to citizens dwelling in complex cities. The stories of this civilisation were first written down in the fourth millennium B.C.E..

The invention of writing was a cultural advance that took place alongside the development of high art and architecture, refined craftsmanship and image making. The creative endeavours of the extraordinary Sumarians involved complex aesthetic structures, ordered and planned spaces and were known collectively as ‘ME’. This word is usually, according to Bahrani, translated as ‘the arts of civilisation’ (Bahrani, 2017, 46). The oldest written texts, which were found in Uruk in Iraq, recorded administrative matters, such as the trade of local produce including cattle and crops. Evidence also existed of other forms of writing in the third millennium B.C.E., and included poetry, sciences and mathematics (Bahrani, 2017).

Why do humans find stories so irresistible?

Prominent thinkers have attempted to answer this question. The classical view was that humans are cooperative and wanted to trade rather than wage war with each other. We only share personal stories when we feel safe and people feel privileged when someone confides in them and builds trust in this way. For this reason, stories may have been an effective means to attain non-kinship ties. These were hard won and even today, families and nations work hard to sustain these links through successive generations. The diplomacy of such bonds requires maintaining trust through high levels of respect and courtesy, verbal and non-verbal social interaction, as well as the sharing of food together. Each level of social bonding would have required a delicate balancing of different perspectives, achieved in such a way that they could not destabilise the all-important trade network.

Perhaps metaphors became important as key negotiating tools of the early traders, when first brokering these networks. The social value of a metaphor for example, could lie in its value as a symbol for relaying sensitive information. Sharing a symbolic reference ( a pair of doves as a gift, representing peace) would build mutual understanding and protect the traders from causing unintended offence. Travelling long distances, they most likely spent considerable time exchanging hospitality with trading partners, and stories would have helped to pass the time, whilst also building bonds of trust.

Most importantly, a story carrying a metaphor could potentially cloak a direct message through its simple arc of beginning, middle and end, and also carry a deeper meaning. The value of sharing a story would have allowed people from different backgrounds to understand one another’s situation from a higher perspective or from a ‘neutral’ point of view.

Anthropologists believe it was possible to build strong networks of social cooperation on a rich understanding of symbolic culture, and this may explain the importance of stories in our evolution in increasingly complex societies. (Dunbar et al., 1999).

Summary

Despite the importance of storytelling for the smaller social groups and the development of large trading networks, its power continuous to mesmerise children and adults alike, whether through films, radio or books. In celebrating World Book Day, many children have created costumes to reflect the characters in their favourite books. This gesture perhaps reminds us all of the importance of stories in our cultural history and prehistory, when humans understood their lives within the narrative of a broader, more cosmic and supernatural context. Although children are not expected to recite poetry as their great grandparents did, it is interesting to see thats superheroes and magical characters are still relevant today. Even more remarkable, the heroes and heroines of today’s literature still embark upon epic journeys of self-discovery, just as they had done thousands of years ago in Homer’s poetry.

Click here to learn how children discovered the joy of reading in our case studies

Click here to book a call.

If you enjoyed this post, why not keep reading and sign up for Free Insights?

Confidence and happiness in the Rhythm for Reading programme

Optimal experiences are life-affirming, intrinsically rewarding and in terms of pedagogy, they are highly desirable because they boost students’ confidence and motivation. They can be very helpful in realigning attitudes towards reward, so that students become motivated by the sheer joy of taking part rather than wanting to know what they will ‘get’ in return for taking part.

Statistically significant impact after only 100 minutes

As the approach is rhythm-based instead of word-based, pupils with specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia or English as an Additional Language (EAL) benefit hugely from the opportunity to improve their reading without using words. It’s an opportunity to lighten the cognitive load, but to intensify precision and finesse.

We all share a common heritage that stems from traditional pre-literate societies in which metaphors have been extraordinarily important tools of diplomacy and ingenuity. Using the richness of imagery, they allowed delicate messages to be conveyed indirectly, thereby fortifying relationships between different groups of people.

Visiting the library for the very first time

This child’s bold plan moved and inspired me to visit the Norfolk Children’s Book Centre to put together a list of books for children who have discovered the joy of reading and are preparing to visit their nearest library for the first time. The Norfolk Children’s Book Centre houses some 80,000 children’s books. As dolphins, dinosaurs and gladiators feature prominently in our resources and are extremely popular with the children, they provided an obvious starting point for our search for these particular books.

REFERENCES

Z. Bahrain (2017) Mesopotamia: Ancient art and architecture, Thames and Hudson Ltd., London.

R. Dawkins, (1976) The Selfish Gene, Oxford: Oxford University press

R. Dunbar, C. Knight abd C. Power (1999) The Evolution of Culture, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

B. Fagan (2010) Cro-Magnon: How the ice-age gave birth to the first modern humans, New York: Bloomsbury Press

J.R. Humphrey (1976)’The social function of intellect, In Bateson P.P.G. and Hinds R.A.. (Eds.) Growing Pains. Ethology Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

M. Wolf (2008) Proust and the squid: The story and science of the reading brain, London: Icon Books

Why empathy boosts reading comprehension in primary schools

23 February 2024

The importance of respect lies at the heart of school ethos and is the foundation for cooperative behaviour and positive attitudes towards learning. In practice, it is possible to cultivate these positive attitudes deliberately, particularly in early reading development if sufficient empathy and sensitivity exists. This means acknowledging cultural diversity - both in depth and breadth, and recognising the linguistic richness of the school community.

Confidence in learning is one of the greatest gifts that education can offer children, but this too requires empathy. Advantaged children start school socially well-adjusted and ready to learn, whereas disadvantaged children lag behind their classmates in this respect. For example, effective teaching that models thinking and reasoning is essential for disadvantaged children, when their attainment is behind age expectation in early reading development. In this post I look at ways in which a focus on empathy breaches social disadvantage and boosts reading comprehension.

Empathy

Let us remind ourselves that the first relationship that infants have is critical to development, because it precedes their own character formation and the sense of self. The primary caregiver is usually the mother in the first weeks of life, but not always. These early weeks of engagement with the infant are thought to influence the child’s development based on two types of maternal caregiving: sensitivity and intrusiveness.These qualities exist at opposite ends of a continuum and there is a general consensus that if the primary caregiver is sensitive about one third of the time, then the child will be socially well-adjusted and attach securely to the mother-figure. Sensitivity refers to the mother’s ability to empathise with her child, to infer her child’s basic requirements, as well as to respond to the child’s need to be soothed or to engage playfully. Traditionally, mothers have responded to their infants’ needs and desires by singing to them, playing peek-a boo style games and reciting stories. The effects of these activities on the developing brain of the infant have been researched and may help us to understand how to support the young children who struggle with early reading when they start school.

Reading Comprehension

The effect of storytelling on the human brain was first reported in 2010 by Silbert and Hasson. The research used a brain scanner to record brain activity as each participant listened to a story. The findings showed, perhaps unsurprisingly that in the auditory areas responsible for processing sound, the brain waves tracked the voice of the person reading the story. However, language areas of the brain and the areas responsible for the sense of self and others, lagged behind the auditory areas. The authors thought that the meaning of the story was being shaped by these slower processes. Further research showed that inserting nonsense words into the story scrambled the areas of the brain, assumed to be involved in processing context and comprehension (Silbert and Hasson, 2010).

According to the well known Simple View of Reading Model (Gough and Tumner, 1986), two foundational skills: linguistic comprehension and decoding are essential for the development of reading comprehension. Decoding is complex: it involves sounding our letters (transforming graphemes into phonemes and syllables) and then blending these into words (Ehri 1995; 1998). Even though individual differences affect the development of decoding, researchers assert that ability in decoding is closely aligned with reading comprehension skill (Garcia and Cain, 2014).

However, individual differences in terms of control of working memory, control of inhibition and the ability to update and adapt with flexibility to the development of the text affect children’s reading comprehension and researchers now think that these abilities also account for the difficulties with decoding as well (Ober et al., 2019). How might teachers make use of this information in a classroom scenario?

Empathy and comprehension in child development

Imagine for a moment that two children have been playing together with a spaceship. The adult supervising them hears that one child has monopolised the toy and the other child is crying in protest. To contain the situation the adult acknowledges and describes the feelings of each child and invites the two children to:

- read one another’s feelings by looking at their facial expressions,

- ask why their friend is feeling this way,

- imagine how they could make this situation better, and

- figure out a way to share the spaceship.

These are important steps because the children then take on a deeper sense of responsibility for:

- self-regulating their own behaviour,

- monitoring their friend’s feelings as well as their own, and

- planning how they might play together to avoid this happening again.

Through playing together, under sensitive professional guidance, these children are able to develop important life skills such as cooperation, learning to adapt to each other’s feelings, as well as planning and executing joint actions in the moment.

It’s also important to recognise that many children do not receive nuanced guidance from adults. Investment in early years provision and training is vital to address the effects of an exponential rise in social and economic disadvantage, but also, sensitivity to culturally and linguistically diverse children for example of asylum seekers and refugees is just as important. Children and adolescents who receive empathic guidance from adults, would for example need to be trusted by the parents of those children, and need to be appropriately culturally and linguistically informed (Cain et al., 2020).

The most important attribute of empathy is that it involves one person being able to connect their personal experiences with those of another individual. Learning about empathy under sensitive adult guidance promotes the development of inhibitive control. Control of inhibition strengthens working memory. Stability and strength in working memory fosters flexibility in thinking. Each of these executive functions lays strong foundations for the development of inference, fluency, and comprehension in reading behaviour, as Maryanne Wolf says,

An enormously important influence on the development of reading comprehension in childhood is what happens after we remember, predict and infer: we feel, we identify, and in the process we understand more fully and can’t wait to turn the page. (Wolf, 2008, p.132)

The adaptive benefit of empathy

The social benefits of empathy are wide-ranging and in terms of human evolution, the ability to act collectively, maintain social bonds and close ties with others has most likely helped our forebears to envision and execute large scale plans for the benefit of a whole community. For example, collections of animal skeletons have led researchers to conclude that more than 20,000 years ago, parties of hunter gatherers had developed killing techniques, honed over generations to take advantage of the seasonal movement of horses. In one site in France, more than 30,000 wild horses were slaughtered, some were butchered, but many were killed unnecessarily and were left to rot (Fagan, 2010).

Humans are like other mammals in the way that we are able to synchronise and move together. When humans gather socially and dance together this behaviour fosters empathy and social cooperation (Huron, 2001;2003).

Indeed, these types of activities have been shown to enhance the development of empathy and school readiness in young children (Ritblatt et al., 2013; Kirschner and Tomasello, 2009;2010), children in primary school (Rabinowitch et al., 2013), and after only six weekly sessions of ten minutes of synchronised movement, entrained to background music, research findings showed significant improvements in reading comprehension and fluency (Long, 2014).

Bringing this back to empathy again, a large scale study involving 2914 children showed that the benefits of shared musical activity were associated with the development of inhibitory control and a reduction of behaviour issues, particularly among socially disadvantaged children (Alemán et al., 2017).

Summary

Our human brains are wired to be social. Our ancestors worked cooperatively and were able to read their environment and infer the seasonal movements of animals. They planned, coordinated and executed hunting plans with devastating precision. Our ability as modern humans to read printed language with fluency, ease and comprehension is perhaps the most advanced act of human social collaboration of all, as it allows us to receive an enormous volume of information from each other about challenges that face us as a global collective. To what extent are we willing to empathise, to infer, to plan and to work together for our common good in an era that demands we now find our common purpose and act upon it?

Why not read about case studies of the rhythm-based approach in schools? Then click here to find out more about the Rhythm for Reading Programme and discuss it with me in person.

If you have enjoyed the themes in this post keep reading.

Conversations and language development in early childhood

Spoken language plays a central role in learning. Parents, in talking to their children help them to find words to express, as much to themselves as to others, their needs, feelings and experiences.

‘As well as being a cognitive process, the learning of their mother tongue is also an interactive process. It takes the form of continued exchange of meanings between self and others. The act of meaning is a social act.’ (Halliday, 1975: 139-140)

Conversations, rhythmic awareness and the attainment gap

In their highly influential study of vocabulary development in the early years, Hart and Risley (1995) showed that parents in professional careers spoke 32 million more words to their children than did parents on welfare, accounting for the vocabulary and language gap at age 3 and the maths gap at age 10 between the children from different home backgrounds.

Mythical tales of abandonment, involving fear of the jaws of death followed by the joy of reunion are familiar themes in stories from all around the world. Sound is a primal medium of connection and communication via mid brain processes that are rapid, subjective, subtle and subconscious. Similarly, the telling of stories, the recitation of poems and songs are also examples of how auditory signals are woven together to communicate for example fear, distress and joyful reunion, or other emotions.

References

Alemán et al (2016) The effects of musical training on child development: A randomised trial of El System in Venezuela, Prevention Science, 18 (7), 865-878

Cain, M. et al (2019) Participatory music-making and well-being within immigrant cultural practice: Exploratory case studies in South East Queensland, Australia, Leisure Studies, 39 (1), 68-82

Ehri , L.C. (1995) Phases of development in learning to read words by sight. Journal of Research in Reading, 18 (2) 116-125

Ehri, L. C.(1998) Grapheme-phoneme knowledge is essential for learning to read words in English. In J.L. Metal & L.C. Ehri (Eds.), Word recognition in beginning literacy (pp.3-40). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Fagan, B. (2010) Cro-Magnon: How the ice age gave birth to the first modern humans, New York, Bloomsbury Press.

Frith, U. And Frith, I (2001) The biological basis of social interaction. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2001, 10, 151-155.

Gough, P.B. and Tumner, W.E. (1986) Decoding, Reading and Reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7 (1), 6-10

Huron, D. (2001) Is music and evolutionary adaptation? ANYAS, 930 (1), 43-61

Huron, D. (2006) Sweet anticipation. The MIT Press

Kirschner, S. & Tomasello, M. (2009) Joint drumming: Social context facilitates synchronisation in preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102 (3), 299-314

Kirschner, S. & Tomasello, M. (2010) Joint music-making promoted prosocial behaviour in 4-year old children. Evolution and Human Behaviour, 31 (5) 354-364

Long, M. (2014) ‘I can read further and there’s more meaning while I read.’: An exploratory stud investigating the impact of a rhythm-based music intervention on children’s reading. RSME, 36 (1) 107-124

Ober et al (2019) Distinguishing direct and indirect influences of executive functions on reading comprehension in adolescents. Reading psychology, 40 (6), 551-581.

Rabinovitch, T., Cross, I. and Bernard, P. (2013) Longterm musical group interaction has a positive effect on empathy in children. Psychology of Music, 41 (4) 484-498.

Ritblatt, S. et al (2013) Can music enhance school readiness socioemotional skills? Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 27 (3), 257-266.

Silbert, G.J. and Hasson, U. (2010) Speaker-listener neural coupling underlies successful communication. Proc. Nate Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14425-14430

Wolf, M, (2008) Proust and the Squid: The story and science of the reading brain, London, UK, Icon Books

Phonics and Executive Functions in Reading Development

24 January 2024

A good education, particularly in reading, sets the foundation for later success. The challenge for schools is to provide a broad and rich curriculum that is ambitious, inclusive and accessible to all children, including the most disadvantaged. As researchers gain a deeper understanding of the human nervous system, brain networks such as the central executive network and its functions, such as working memory, cognitive flexibility and control of inhibition, we as educators are able to embrace innovative approaches with greater confidence, and bridge gaps in children’s development that need to be addressed.

Following the COVID pandemic and the current ‘cost of living crisis’, over a quarter of children are not reaching a good level of development by the age of five. Delays for example, in spoken language skills are likely to affect the development of executive functions such as emotional self-regulation, inhibitory control and sustained attention. Subtle or profound impairments in early reading skills and executive functions may have a cascading impact on educational success, well-being and good health.

If young children start to learn to read with limited skills in executive function, they may struggle to allocate the cognitive resources necessary for processing text, with slower or more effortful decoding, which would impact the development of new vocabulary and place increased demand on cognitive resources, setting up a negative spiral.

According to the so-called ‘Matthew Effect’ (Stanovich, 1986) ‘the rich get richer and the poor poorer,’ the children who fall behind in reading, continue to fall behind as they go through school. This spiralling effect has been described as a reciprocal relationship between the efficiency of decoding and the development of executive functions (Stanovich, 2009). Indeed, longitudinal studies have linked warm and responsive parenting with good levels of development in:

- executive functions such as sustained attention and emotional self-regulation,

- spoken language skills prior to starting pre-school,

- fluency and enjoyment in reading,

- later academic achievement.

Phonics and executive functions

The most obvious milestones of child development include learning to walk, run, jump and talk, but executive functions are relatively nuanced and reach maturity in early adulthood. They include the a child’s ability to regulate their emotions, sustain their attention, suppress their impulses and choose goal-directed rather than impulse-driven behaviour.

It is interesting to consider the relationship between executive functions and phonics because executive functions are generally regarded as ‘top down’ processes, whereas language is processed from the bottom up, primarily as a sensory experience, whether through speaking, reading or listening. However, in the context of decoding the words on the page, a child in the early stages of learning to read must tackle word reading as a code breaker would using various tools:

- phonological awareness,

- knowledge of the relationship between letters and sounds,

- visual memory of the shape of the word,

- cues provided by the context.

If we focus in on this problem-solving aspect of learning to read, we can see why ‘top down’ processes such as executive functions are so important. In this post, I’ll discuss the executive functions of working memory, cognitive flexibility and control of inhibition. However, the control of sustained attention, which is also considered an executive function, is a prerequisite for focused reading and learning (Diamond, 2013). If a child is hungry, tired or anxious, even in the most calm, orderly and consistent of learning environments, they are likely to struggle to focus their attention and their other executive functions: the development of learning and reading is therefore arrested for the most fundamental of reasons.

Phonics and working memory

Given that executive functions develop throughout childhood and adolescence, it is not surprising that researchers have found a general correspondence between the development of decoding ability and executive functions. Therefore, as children develop into fluent readers, they rely less on the problem-solving aspect of decoding and on maintaining the letters and their corresponding sounds in working memory while they decipher each of the syllables in turn. However, decades of research have provided evidence of an association between working memory and decoding skills for children with fragile reading.

A key difference between fragile and fluent readers has been explained by the Dual Route Model of visual word recognition and reading aloud (Coltheart, et al. 2001). According to this model, during the development of early reading, decoding skills require both a phonological processing route (for the smallest sounds of language) and an orthographic route (for the visual recognition of the whole word). Children with fragile reading tend to spend more time and effort in the phonological route, whereas children with fluent reading are able to recognise whole words without an emphasis on effortful and slower phonological processing. This learning difference is likely to cascade into all areas of learning, leaving the fragile reader struggling with fatigue in the long term, unless their reading becomes fluent.

Phonics and task-switching

‘Task-switching’ is also known as ‘cognitive flexibility’. Imagine a bi-lingual child who speaks a different language depending on the context. Perhaps they speak English at school and a different language at home. This ‘top down’ switch from one language to another is an example of the type of shift that children learn to make in many areas of everyday life.

The Dual Route Model offers a way to understand the role of ‘task-switching’ in reading development. Reading experts (Cartwright et al., 2017) have argued that fluent readers have the ability to toggle between phonological and whole word processing, whereas novice readers do not and the researchers attribute this flexible dimension of reading fluency to ‘task switching’. As we have already seen, the need to apply this level of flexibility and ‘top down’ control would decrease as reading fluency develops (Guajardo and Cartwright, 2016).

Phonics and control of inhibition

Inhibitory control plays an important role in children’s learning behaviour. It is obvious that some children are very distractible and chatty in class. Those who cannot focus their attention and suppress internal impulses at will are more likely to struggle with hearing the smallest units of language (phonemic awareness). A longitudinal study that tracked the reading development of children from kindergarten (age five) to second grade (seven years of age) demonstrated an indirect relationship between inhibitory control and phonological awareness (Van de Sande et al, 2017). Another study (Ober et al., 2019) focused on adolescents and demonstrated associations between their decoding ability, inhibitory control and task-switching, which underscores the need to remediate struggling readers as soon as they are identified.

A Meta-analysis

Although an association between executive unctions and reading comprehension has already been established, the relationship between executive functions and decoding skills requires a degree of clarification, partly because decoding skills and executive functions mature in tandem in typically developing children (Ober et al, 2020).

A meta-analysis was conducted by Ober and colleagues (2020). Across 65 studies, covering a wide range of languages there were 165 significant associations between decoding and executive function skills and the mean effect size was ‘moderate’ for both word reading and nonword reading. In a large sample, it is easier to achieve statistical significance, but far harder to achieve an effect size of this magnitude, which indicates the considerable strength of the relationship.

The meta-analysis showed that associations were significant and generated moderate effect sizes for the following executive functions:

- working memory and word reading (as well as nonword reading)

- task-switching with word reading (as well as nonword reading)

- inhibitory control with word reading (as well as nonword reading)

Characteristics of different languages

Languages such as English, French, Chinese or Arabic have relatively deep orthographies, which means that the relationship between the sounds of words and the way that they are written is multi-layered. This is because of the way the language developed over thousands of years. Languages such as Spanish and Greek are mainly regular in the relationship between the sounds of language and their appearance on the page.

As a consequence, in English, words such as, ‘said’ or ‘water’ are taught by visual recognition as they cannot be learned by relying on entirely the smallest sounds of language (phonemes) to lead the child to the correct spelling.

In 1969 a team of researchers (Berdiansky and colleagues) looked at the 6,092 most common one and two syllable words extracted from the schoolbooks of children aged between six and nine. They found that there were 211 symbol-to-sound correspondences and of these, 166 could be described as rule-based, whereas 45 were exceptions to these rules. A rule was established if it occurred at least ten times in the 6092 words.

In the meta-analysis the various languages were organised into two groups:

- Deep orthographies: Chinese, English, Danish, French

- More transparent orthographies: Croatian, Dutch, German, Greek, Spanish, Turkish

The researchers looked at the extent to which age interacted with the effect sizes in the studies. Interestingly, the effect of age on these data depended on which executive function was studied, with age as a predictor of performance on ‘task-switching’. Here, the association between decoding and task-switching became smaller as the age of participants increased.

Drilling down into the data, the researchers found that the longitudinal studies (which tracked children’s performance on working memory, task-switching and inhibitory control and decoding over time), showed that the strength of the relationship between executive function skills and decoding was more reliable in early rather than late childhood.

With respect to different types of language, those with deep orthographies were more likely to demand a more frequent toggling pattern between the phonological and the orthographic processing routes during reading development, but the need to toggle would diminish with age once reading fluency has been established.

However, for weaker readers who do not develop reading fluency, a language with a deep orthography such as English provides an additional challenge in terms of ongoing effortful phonological processing and falls into a spiral of diminishing returns, as increased effort leads to cognitive fatigue and a sense of disempowerment.

If you are interested in finding out more about how the Rhythm for Reading programme can help, click here.

If this topic is of interest, keep reading!

Supporting children with a ‘fuzzy’ awareness of phonemes and other symptoms consistent with dyslexia

If we turn to auditory problems faced by people with dyslexia, there are two interesting things to consider. One is fuzzy phonemes. Phonemes are the smallest sounds of language. If we break the sound wave of a phoneme down into its beginning, middle and end, this can help us to think about the very first part of the sound. Among children with dyslexia, there is a lack of perceptual clarity at the front edge of a phoneme.

When phonics and rhythm collide part 1

A child with sensitivity to rhythm is attuned to the onsets of the smallest sounds of language. In terms of rhythmic precision, the front edge of the sound is also the point at which the rhythmic boundary occurs. Children with a well-developed sensitivity to rhythm are also attuned to phonemes and are less likely to conflate the sounds.

When phonics and rhythm collide part 2

Vowel sounds carry interesting information such as emotion, or tone of voice. They are longer (in milliseconds) and without defined edges. Now imagine focussing on the onset of those syllables. The consonants are shorter (in milliseconds), more sharply defined and more distinctive, leaving plenty of headspace for cognitive control. If consonants are prioritised, information flows easily and the message lands with clarity.

Phonemes and syllables: How to teach a child to segment and blend words, when nothing seems to work

There is no doubt that the foundation of a good education, with reading at its core, sets children up for later success. The importance of phonics is enshrined in education policy in England and lies at the heart of teaching children to become confident, fluent readers. However, young children are not naturally predisposed to hearing the smallest sounds of language (phonemes). Rather, they process speech as syllables strung together as meaningful phrases.

REFERENCES:

Berdiansky, B., Cronnell, B. And Koehler, J. (1969) Spelling-sound relations and primary form-class descriptions for speech comprehension vocabularies of 6-9 year olds. Technical Report No 15. Los Alamantos. CA. Southwet Regional Laboratory for Educational Research and Development

Cartwright, K.B., Marshall, T.R., Dandy, K. L. and Isaac, M. C. (2017) Cognitive flexibility deficits in children with specific reading comprehension difficulties, Contemporary Educational Psychology, 50, 33-44

Coltheart, M.,Rastle, K., Perry, C., Langdon, R. And Ziegler, J. (2001) DRC: A dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud, Psychological Review, vol.108, no.1, pp. 204-56

Diamond, A. (2013) Executive functions. Annual Review of psychology, 64, 135-168

Guarjardo, N.R. and Cartwright, K.B. (2016) The contribution of theory of mind, counterfactual reasoning and executive function to pre-readers’ language comprehension and later reading awareness and comprehension in elementary school. Journal of Experimental Child psychology, 144, 27-45.

Ober, T.M., Brooks, P.J., Plass, J.L. & Homer, B.D. (2019) Distinguishing direct and indirect effects of executive functions on reading comprehension in adolescents. Reading psychology, 40 (6), 551-581.

Ober, T.M., Brooks, P.J., Homer, B.D. and Rindskopf, D. (2020) Executive functions and decoding in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic investigation, Educational Psychology Review,

Perfetti, C. (1985) Reading ability, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Perfetti, C. (2007) Reading ability: Lexical quality to comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 20 (4) 325-338

Stanovich, K.E. (1986) Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21 (4), pp.360-407

Van de Sande, E., Segers, E., & Verhoeven, L., (2017) how executive control predicts early reading development. Written Language and Literacy, 20 (2), 170-193

Learn to read music and develop executive functions: The exception rather than the rule

17 January 2024

The narrowing of the curriculum has squeezed the arts and humanities and this is likely to affect pupils from a lower socio-economic status (SES) background more than relatively advantaged children, according to the Sutton Trust (Allen & Thompson, 2016). In England, headteachers are tasked with challenging the effects of economic disadvantage by ensuring children are able to access a broad and balanced curriculum, rather than an impoverished one. However, given that the allocation of teaching time is such a precious resource, how might primary schools devise a curriculum that includes musical notation? Traditional approaches are time-consuming and use complex mind-boggling mnemonics that are not sufficiently inclusive. However, a rhythm-based approach avoids cognitive loading and requires short weekly sessions of about ten minutes. This uses short, sharp quick-fire responses that are fun and facilitate group learning.

Teaching musical notation with a sense of mastery

The Rhythm for Reading Programme creates an environment that allows pupils to focus their attention right from the start. They learn to read music by repeating, reviewing and practising key concepts each week, consistent with the principle of ‘spaced practice’. Consistent rehearsal of musical notes using visual images, as well as hearing and saying the note names, illustrates the principle of ‘dual coding’. The programme is built on a cumulative structure that prioritises fluency, as well as a light ‘cognitive load’ and there is a gradual increase in the complexity of tasks within the context of working together as a strong and enthusiastic team.

There is minimal input in terms of ‘teacher talk’. Instead, explicit instructions from the teacher, based on the rubrics of the programme outline the specific details of each task. This approach is known to support novice learners and a clear expectation on the part of the teacher is that every child contributes to the team effort and is key to the programme’s impact.

Teaching musical notation and cultivating executive functions

The Rhythm for Reading Online Training Programme offers individually tailored CPD.

Teachers are immersed in a completely new knowledge base and a comprehensive body of work, including theory, research and practice, that has successfully evolved over a period of three decades.

The Rhythm for Reading approach stimulates children’s executive functions using simple repetitive techniques that feel like a fun group activity and are easy for all children to master.

The programme has been shown to transform reading development in:

- young people with severe learning needs in a special education setting

- Pupil Premium children in mainstream schools

- children with specific learning difficulties

- children who simply need a ‘boost’ in their reading

By following the simple rubrics and rhythm-based exercises of the online programme, teachers are able to accelerate children’s reading development and cultivate their executive functions during ten weekly sessions of about ten minutes.

Teachers need to practise using these fresh and exciting new teaching methods for at least a couple of terms. Ongoing mentoring support is available throughout the programme, as is follow-up support. For further details click here.

As teachers develop a practical understanding of how to nurture children’s executive functions through rhythm-based exercises, they feel empowered by changes in the children’s progress.

Reading fluency is monitored by teachers throughout the programme using a dedicated ‘Reading Fluency Tracker’ which takes two minutes to complete each week. There is also, if needed, an option to focus on deeper levels of assessment of learning behaviour.

Teacher enrichment and reflexive practices are keystones in the CPD of the Rhythm for Reading programme and there is a strong emphasis on supporting teachers’ well-being. A workbook is available for teachers to record their personal experiences of the programme and these can be referenced in weekly one-on-one mentoring calls.

Research Studies in Music Education

Research on the benefits of music training to executive function is inconclusive. According to academics, the mixed bag of findings reflects differences in the types of musical activities. At present, the relationship between musical training and any effect on executive functions is unclear to the music education research community. However, based on a review of the latest research, academics offered this recommendation:

Ideally music lessons should incorporate skills that build on one another with gradual increases in complexity. (Hallam and Himonides, 2022; p.197).

Potential exists for each executive function to play an important role in music making as follows:

- Inhibitory control is essential to the element of teamwork in music-making, such as community singing, where people are encouraged to participate with others in a balanced and proportionate way.

- Cognitive shifting, also known as cognitive flexibility, is activated every time a change occurs in a melodic or rhythmic pattern, and also when the relationships between the musical lines or voices, also known as the texture, changes.

- Working memory is constantly activated in the same way that it would be in a conversation, with updating, assimilating and monitoring, as a person participates in the music.

- Sustained attention is necessary for the coordination of cognitive shifting and working memory. Just as interaction in a conversation is predictable at the beginning and the end, but may have a ‘messy middle’ (a loss of predictability), the same can be said to exist in music.

- To maintain the necessary level of sustained attention in the dynamic activity of music making, each performer engages inhibitory control of internal and external distractions.

In a particularly well-controlled, and therefore robust study, there were strong positive effects of musical training on executive functions, particularly inhibitory control among children (Moreno et al., 2011, cf. Hallam and Himonides, 2022).

Although the expressions, ‘getting lost in the music’ and ‘getting lost in a book’ are figurative and imply a perception that the external world has temporarily ‘ceased to exist’, there is also an implication that the individual has entered into a meditative ‘flow state’, suggesting that the executive functions are working together in a coherent and self-sustaining way.

Reading musical notation, reading a text and executive function

Given that musical notation as a symbol system that describes what should happen during music making, there is a strong logical argument for musical notation to act as a stimulus for activating executive functions.

A ‘Yes-But’ response resounds at once because the research literature is ‘mixed’ in terms of findings. Bear with me as I offer a few thoughts…

When researchers used a brain scanner to study the parts of the brain involved in reading musical notation, they asked professional musicians to read musical notes, a passage of printed text and a series of numbers on a five-key keypad (Schön et al., 2002, cf. Hallam and Himonides, 2022). Unsurprisingly, similar areas of the brain were activated during each type of reading activity. Over millennia humans have developed many symbol systems, including leaf symbols, hieroglyphs, cuniform, alphabets and emojis. This research is very reassuring as it suggests that the brain adopts a standard approach for reading different symbol systems. As there was no evidence that reading musical notation was any different to reading text or numbers, then presumably musical notation and other types of reading share the same neural structures. If this is the case, then this might explain an acceleration of reading skills in struggling readers after a six-week intervention in which children learned to read musical notation fluently (Long, 2014).

Reading musical notation differs from reading text or numbers in one important way: each symbol has a precise time value, which is not the case when we read words or numbers. However, when reading connected text or musical notation, there is an important element that is relates directly to rhythm, which is that musical phrases and sentences tend to be read within similar units of time. By coincidence (or by way of an explanation), this time window happens to fit with our human perception of the duration of each present moment.

So, given that working memory fades after about five to seven seconds of time have elapsed, we can understand that musical phrases and utterances in spoken language are closely tied to executive functions of working memory and sustained attention.

Reading musical notation and executive function

Many people’s experience of reading musical notation begins at the moment when they are learning to play a musical instrument. The physical coordination required to produce a well-controlled sound on any musical instrument draws upon sustained attention, working memory, and cognitive flexibility (adapting to the challenges of the instrument). The engagement of these executive functions in managing the instrument may leave very few cognitive resources available for reading notation, leading to frustration and a sense of cognitive overload.

Using the voice rather than an instrument offers a possible solution, as singing is arguably the most ‘natural’ way to make music. Learning a new song however, involves assimilating and anticipating both the pitch outline and the words before they are sung. As these tasks occupy working memory, it is possible that cognitive overload could arise if reading notation while learning a new song.

Chanting in a school context - a rhythm-based form of music-making that humans have practised for thousands of years, whether in protest or in prayer is relatively ‘light’ in terms of its cognitive load on working memory. All that is required is a short pattern of syllables or words. Repetition of the pattern allows the chant to achieve a mesmeric effect. This can be socially bonding, hence the popularity of chanting in collective worship around the world.

Although researchers have demonstrated that musically trained children have higher blood flow in areas of the brain associated with executive function (Hallam and Himonides, 2022 ), it is important that researchers specify the musical activities that activate executive functions.

Comparing the three options: learning an instrument, a song or a chant - it is clear that they could develop executive function in different ways.

Learning to play a musical instrument demands new levels of physical coordination, involves deliberate effort and activates all of the executive functions for this reason.

Learning a new song places a high demand on verbal and spatial memory (working memory) as the pitch outline and the words of a song must be internalised and anticipated during singing.

Learning a simple chant places minimal demand on cognitive load. This makes it is easy for individuals drop into a state of ‘autopilot’, allowing the rhythmic element of the chant to keep their focus and attention ‘ticking over’ without deploying executive function.

So, chanting, with its lighter cognitive load offers the most inclusive option for teaching musical notation in these settings:

- in mixed ability groups in mainstream schools

- among children with learning differences in mainstream or special educational schools

You might be thinking surely, ‘mindless’ chanting has no place in 21st century education? Yes, I would agree - but the exception to this notional rule would be this: chanting is appropriate for children with fragile learning and reading if they also display hypo-activation of executive function:

- weak attention,

- limited working memory

- poor impulse control

- slow cognitive switching

Children with weak executive functions are better able to learn to read musical notation using chanting (rather than playing an instrument or singing) for the reasons outlined above. A rhythm-based approach (using a structured and cumulative method) restores executive function and reading development among these children in a very short period of time.

According to Miendlarenewska and Trost (2014) enhancing executive functions through rhythmic entrainment in particular would drive improved reading skills and verbal memory: the impact of the Rhythm for Reading programme bears this out (Long, 2014; Long and Hallam, 2012).

If you enjoyed reading this post, keep reading:

A simple view of reading musical notation

Many people think that reading musical notation is difficult. To be fair, many methods of teaching musical notation over-complicate an incredibly simple system. It’s not surprising that so many people believe musical notes are relics of the past and are happy to let them go - but isn’t this like saying books are out of date and that reading literature is antiquated?

Musical notation, a full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection

Many years ago, I was asked to teach a group of children, nine and ten years of age to play the cello. To begin with, I taught them to play well known songs by ear until they had developed a solid technique. They had free school meals, which in those days entitled them access to free group music lessons and musical instruments. One day, I announced that we were going to learn to read musical notation. The colour drained from their faces. They were agitated, anxious and horrified by this idea.

Empowering children to read musical notation fluently

Schools face significant challenges in deciding how best to introduce musical notation into their curriculum. Resources are already stretched. Some pupils are already under strain because they struggle with reading in the core curriculum. The big question is how to integrate musical notation into curriculum planning in a way that empowers not only the children, but also the teachers.

Teaching musical notation, and inclusivity

For too long, musical notation has been associated with middle class privilege, and yet, if we look at historical photographs of colliery bands, miners would read music every week at their brass band rehearsals. Reading musical notation is deeply embedded in the industrial cultural roots. As a researcher I’ve met many primary school children from all backgrounds who wanted to learn to read music and I’ve also met many teachers who thought that reading music was too complicated to be taught in the classroom.This is not true at all! As teachers already know the children in their class and how to meet their learning needs, I believe that they are best placed to teach musical notation.

References

Allen & Thompson (2016) “Changing the subject: how are the EBacc and Attainment 8 reforms changing results? The Sutton Trust,

Hallam, S. and Himonides, E. (2022) The Power of Music: An exploration of the evidence, Cambridge, UK, Open Book Publishers

Long, M. (2014). ‘I can read further and there’s more meaning while I read’: An exploratory study investigating the impact of a rhythm-based music intervention on children’s reading. Research Studies in Music Education, 36 (1) 107-124

Long, M. and Hallam, S. (2012) Rhythm for reading: A rhythm-based approach to reading intervention. [MP282] Proceedings of Music Paedeia, 30th ISME World Conference on Music Education, pp. 221-232

Miendlarenewska, E. A. and Trost, W. J. (2014) How musical training affects cognitive development: rhythm, reward and other modulating variables. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7.

Moreno, S., Bialystok, E., Barac, R., Schellenberg, E.G., Capeda, N. J. & Chau, T. (2011). Short-term music training enhances verbal intelligence and executive function, Psychological Science, 22 (11), 1425-1433

To what extent is reading comprehension supported by executive functions?

10 January 2024

Although it is widely known that information is best presented with a degree of repetition, as well as by repeating and reviewing key concepts, such an approach is most effective when pupils are able to read widely and often, with fluency and comprehension. Decades of research point to the importance of self-regulation and metacognitive awareness as key predictors of reading comprehension and the ability to access a broad and rich curriculum. Teaching in small chunks with repetition and being mindful of activities that require too much memory capacity in the spirit of ‘cognitive load theory’ is likely to hold many pupils back, so in this post I examine the relationship between reading comprehension, executive functions and rhythm-based teaching.

What are executive functions and why do they matter?

Just as we may need to ‘read the room’ to gauge a social context, mood and emotional tone, we also need to ‘read’ information on the page or screen with the same level of sensitivity and awareness. However, while the dynamics of a live social situation, or the events of a movie play out in real time before our eyes and ears, the situation on the page requires a more sustained and selective engagement on the part of the reader if they are to extract and assimilate the maximum understanding of the text.

This level of engagement involves ‘metacognition’, which is an aspect of social understanding that requires a person to monitor the degree to which they are successfully appraising a situation.

Metacognition is a form of social awareness, whereas self-regulation is more about a person’s awareness of their own behaviour and priorities.

Self-regulation is a form of goal-directed behaviour that includes:

- prioritising relevant actions,

- inhibiting (suppressing) those that are less relevant.

Therefore, inhibition is a core aspect of self-regulation. Both metacognition and self-regulation can facilitate reading comprehension in terms of the degree of overall engagement. There is also a more dynamic quality to understanding a text, which involves:

- being able to adapt flexibly to the development of the narrative,

- the shifting of perspective as necessary in order to maintain comprehension.

So far we have considered forward planning, cognitive flexibility - also known as ‘shifting’,and control of inhibition. These elements of cognitive control are referred to under the ‘umbrella term’, ‘executive functions’.

Are executive functions mentioned in the Simple View of Reading?

When people read a text, they draw upon prior knowledge, whether they realise it or not. They assume that the most likely course of events will unfold. For example, baking a cake precedes eating a cake. An unexpected turn of events might derail this assumption if say, the cake turned out to be a birthday present. Under the altered circumstances, the reader would adapt and apply a new schema (prior knowledge of birthday cakes) and reappraise their orientation and understanding of the text.

One of the most discussed aspects of executive function, ‘working memory’, varies considerably between people. In the context of language comprehension, in speech and in print, ‘working memory’ holds fragments of information in such a way that new information can be assimilated immediately, enriching, evolving and expanding previous impressions. Encoding (the process of updating or taking in information from the senses) is likely to involve both verbal and envisioned impressions, as creating this record of verbal information in the form of an image (like a movie in the mind) helps to enhance long-term memory formation.

In social situations, people tend to use language to imply what has taken place, and this means that an important part of social engagement involves filling the gaps with inferences that make use of tone of voice, gestures and facial expression, for example. Children with a limited working memory capacity are more literal in their response to language - relying more on a skeleton framework, whereas those with a more capacious working memory are more likely to enjoy a more playful and exploratory approach, to making these inferences.

In the Simple View of Reading (SVR), Gough and Tumner (1986) stated that reading comprehension is predicted by fluent decoding skills and oral language skills. Their model did not included executive function. Given that working memory, inhibition, sustained and selective attention, and cognitive flexibility underpin reading comprehension, this would appear to be an overly simplistic view.

However, in a study that examined the role of executive functions on young children’s reading comprehension (Dolean et al, 2021), a large proportion of the variance in reading scores was explained by executive function at the initial (baseline) testing, but not at the follow-up six months later. The authors noticed that this outcome was likely to be due to the high number of fluent decoders in their sample. However, language skills at baseline did predict reading comprehension in the follow-up tests. The researchers seemed to assume that executive functions, like language skills would accumulate with time in children. It is possible that these are more dynamic than language skills and are more likely in the short term to change in response to the immediate environment.

The relationship between executive functions, reading comprehension and rhythm-based training.

An interesting pattern has emerged from the research literature on the development of reading comprehension:

- Struggling readers rely more on fluent decoding.

- Fluent readers rely more on oral language skills.

The effects of executive functions on reading comprehension scores were stronger among children who relied on decoding rather than language skills

This findings bring us back to a ‘common sense view’ of reading comprehension which is:

- Weaker executive functions such as working memory, control of inhibition, attention and cognitive flexibility are associated with children who rely more on decoding strategies in their reading comprehension.

- Children who rely more on oral language skills and less on decoding, access reading comprehension with minimal effort in terms of executive function.

If performance on executive functions does predict fluent decoding in reading development, then it follows that changes in executive function would impact fluent decoding and influence reading comprehension scores.

There are many studies showing the effects of musical training on executive function (Hallam and Himonides, 2022). In particular, these studies have repeatedly shown the benefits of rhythm-based training on working memory. One recent study, measured working memory before and after a rhythm-based music intervention in young Finish children, and showed a statistically significant effect of:

- rhythm-based training on working memory,

- improved reading development among the children with lower baseline reading scores.

The three studies mentioned in this blog post point to three key findings:

- the importance of executive function for the development of reading,

- that children who are more likely to struggle with reading at school are more likely to need support through the development of executive function,

- that rhythm-based training supports the development of executive function among children who have lower baseline reading scores.

Rhythm and executive functions

The studies also showed that we can think of executive functions as ‘team players’ in the following way:

- Inhibitory control is an important element of sustained and selective attention and self-regulation.

- Sustained and selective attention is an important component of working memory.

- Working memory capacity enables cognitive flexibility.

- Cognitive flexibility and working memory capacity enable metacognition.

As teachers are well-aware, if executive functions are limited or imbalanced, they can lead to low-level disruption in the classroom, and the extent to which a positive day-to-day learning environment can be maintained.

Schools using the Rhythm for Reading programme have discovered it has developed children’s executive functions. For over a decade, many children have benefited from the effects of the ten week programme of rhythm-based training (only ten minutes per week) with substantial improvements in:

- Reading behaviour - accuracy, fluency and comprehension,

- Sustained and selective attention - better ability to focus and concentrate in the classroom,

- Improved working memory - increased assimilation of meaning while reading - ie comprehension,

- Inhibitive control - stronger self-regulation and the ability to ignore distractions and complete given tasks,

- Cognitive flexibility - improvement in updating and predicting the likely direction of events in the passage of text,

To learn more about the Rhythm for Reading programme and executive function, click here.

To read about our results in case study schools, click here.

To discuss having Rhythm for Reading in your school, click here to book a discovery call.

If you enjoyed this post on reading comprehension, keep reading!

How does the Rhythm for Reading programme actually work?

The logical forms and hierarchical structures that are integral to the Rhythm for Reading audio-visual resources automatically train children to recognise grammatical structures, align with phrase contours and activate the associative priming mechanism (Jones and Estes, 2012) while they read printed language (Long, 2014).

Three factors to take into account when assessing reading comprehension

Factor one: There is minimal cognitive loading of working memory as the child can refer back to the text when answering questions. In other words, they do not need to remember the passage of text, whilst answering the questions. This approach prevents a conflation between a test of comprehension and a test of working memory. Children may score higher on NARA II if working memory is likely to reach overload in other reading test formats, for example, if the child is required to retain the details of the text whilst answering comprehension questions.

Rhythm and Reading Comprehension 1/5

In the Simple View of Reading, reading comprehension is described as the ‘product of’ skilled decoding and linguistic comprehension (Gough & Tumner, 1986). A focus on oracy (for example Barton, 2018) highlights a focus in some schools on linguistic comprehension. According to researchers, the proportion of children beginning school with speech, language and communication needs is estimated at between 7 and 20 per cent (McKean, 2017) and unfortunately, communication issues carry a risk of low self-esteem and problems with self-confidence (Dockerall et al., 2017).

References

Ahokas et al., (2023) Rhythm and reading: Connecting the training of musical rhythm to the development of literacy skills,PsyArXiv; 2023. DOI: 10.31234/osf.io/7ehwu.

Dolean, D. et al., (2021) Language skills, and not executive functions, predict the development of reading comprehension of early readers: evidence from an orthographically transparent language, Reading and writing, 341: 1491-1512.

Gough, P.B. and Tumner, W. (1986) Decoding, reading, and writing disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6-10.

Hallam, S. and Himonides, E. (2022) The Power of Music: An Exploration of the Evidence, Cambridge UK: Open Book Publishers

Is learning to read music difficult?

6 December 2023

Some of the most sublime music is remarkably simple to read. Just as the balance of three simple ingredients can make your taste buds ‘pop’, a few notes organised in a particular way can become iconic themes. The opening of Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ and the beginning of the ‘Eastenders’ theme by Simon May are examples of this - as is ‘Jingle Bells’ - (as we are now in December). The point I want to make is that music, like nature, requires balance if it is to feel and sound good. We humans are part of the natural world and our music - varied as it is - is an important part of our natural expression. By this I mean that like other species, we use our voices to attract, bond with, (or repel) each other, socially. In the past two thousand years, music has been written to represent the full range of our social behaviours: from the battleground to the banqueting hall, from the wedding to the funeral, the shop floor to the dance floor, the gym to the sanctuary. We use music to regulate our emotions, to develop our stamina and to motivate ourselves as social groups which behave in particular ways.

We don’t need to read music to enjoy singing with friends at a party or to chant with fans at a sports stadium or to create our own music in the quiet of our own homes. However, if we want to share our own process of creating or performing music, we need to notate it (to write it down) so that we are literally ‘on the same page’ and therefore are able to collaborate more efficiently.

Can you learn to read music without an instrument?

It is very easy to learn to read music ‘without an instrument’ because our voice is our natural instrument. It is also possible to imagine a sound - in the same way that one can imagine a colour or a shape. Musicians can ‘read’ a sheet of music and use the ‘inner ear’ to hear the sounds. When we read a book, our inner voice reads the words in a similar way.

A debate raged for a long time in music education around the idea of ‘sound before symbol’. Some people believed that children were a ‘blank slate’ and needed to learn musical ‘sounds’ before they saw musical symbols in notated form. Others argued that children knew songs before they even started school, and could a manage a more demanding approach such as, ‘sound with symbol’. Fortunately, the era in which ‘sound before symbol’ dominated is now over and teachers can teach musical notation without being regarded as deviant or backward looking. Expensive musical instruments are not necessary for learning to read music. Each child’s voice is a priceless musical instrument, and every child can benefit by developing its use.

Music for health and well-being

Humans have been using music for self-expression for thousands of years. It has been used by people to manipulate perceptions of potential competitors or predators. In situations where people have felt threatened, singing together has helped them to feel strong and brave. Sea shanties are an example of this and in traditional societies people sing through the night to make themselves appear ‘larger’ to predatory animals. To regulate and balance the nervous system, people all around the world soothe themselves through music when they are dealing with grief, using elegies, dirges and laments. When parents comfort infants and young children they sing lullabies to them and also provide a rocking motion, which can ‘lull’ them to sleep.

The human voice can signal alarm through a blood-curdling scream, but it can also provide comfort through well chosen words. Musical expression mirrors this wide range of functions, but it goes much further than language by making use of the exhaling breath. Manipulating the slow exhale, humans have discovered how to shape the voice into elaborate patterns. We can hear this particularly in gospel and operatic traditions - where the feel of improvisation involves an outpouring of emotion. Is it possible to notate these beautiful elaborations? Yes they can be transcribed, but their beauty lies in their spontaneity and the feeling that they emerged from an impulse in a moment of inspiration.

Why do some people struggle to read music?

This is a great question. Given that I’m arguing for music as the natural ‘song’ of our species, why would this natural behaviour flow more easily through some people than others?

Reading as a skill is quite a recent addition to our repertoire of social behaviours. Music and language are natural to us and are ‘hard-wired’ into our nervous system, whereas reading is not - but we are able to learn to read. This skill is well-practised as humans have been using various signs and symbols to communicate for tens of thousands of years.

The main difference between reading music and reading words is that the rhythmic patterns in music are relatively inflexible, whereas printed language is rhythmically malleable. A three word phrase in a printed conversation, such as, ‘I don’t know’ can be reinterpreted by adapting the rhythmic qualities to convey a full range of emotions from exasperation to mystification. When we read, we are guide by the context of the passage. The context would help the reader to identify the most appropriate rhythm for the words. In this respect, rhythm in language reflects context as much as it does the underlying grammatical structure of the sentence.

When reading music, the prescribed rhythmic element reflects the musical context and style. A march, a samba and a ballad each have their own distinctive rhythmic feel. Repeated patterns need to be rhythmically consistent to sound ‘catchy’ or convincing. In this way, rhythm is the stylised and ritualised aspect of music and it can even be hypnotic. This quality in rhythm is the reason it is used by people as a motivational tool, or for self-regulation when the nervous system feels dysregulated.

When reading music, some people struggle to process the rhythmic element. The same people may struggle to move in time with the beat, but this is certainly not an insurmountable problem. It is a question of placing an emphasis on feeling the rhythm first, and then reading the rhythm, once the feeling has been established. This is not always easy because people sometimes feel anxious and believe that they are not ‘rhythmical’ enough.

Children who struggle to read printed language, have learned to read simple musical notation with ease and have responded very well to the Rhythm for Reading Programme. There is a remarkable shift in these children when they realise that by reading musical notation as a group, and through a very profound experience of well-being, belonging and togetherness that this brings, their reading fluency and comprehension also improve.

Our very simple introduction to musical notation involves:

- working with music that is rhythmically balanced,

- an atmosphere that is informal,

- music-making that is joyful.

How to long should it take to learn to read music?

It takes only a few minutes to learn to read simple musical notation. Even children with very weak language reading skills can achieve fluent reading of musical notation in only ten minutes. We focus on integrating each sensory aspect of reading music: the children’s eyes, ears and voices. Children are able to bring their attention into sharper focus when they read musical notation because the rhythmical element, which for them represents emotional safety, has been addressed through our highly structured approach.

If you have enjoyed reading about musical notation…

Click the red button at the top of this page to receive weekly updates from me every Friday.