Rhythm and Reading Comprehension 1/5

29 April 2018

‘To be understood - as to understand’ from the prayer of St Francis captures a profound truth: we are at our happiest when we feel truly understood by others. This feeling of mutual understanding strengthens communities and generates an aura of certainty at the core of each individual’s character. The ability to understand exists in all of us, but can easily be obscured by doubt, worry or fear. Removing worries, doubts and fears leads to clarity –as Johnny Nash put it, “I can see clearly now the rain has gone…”. The same principle applies to reading comprehension. The songlike qualities of speech (i.e. prosody) come to life in children’s voices when they are able to read with ease, fluency and understanding.

In the Simple View of Reading, reading comprehension is described as the ‘product of’ skilled decoding and linguistic comprehension (Gough & Tumner, 1986). The recent focus on oracy (for example Barton, 2018) highlights a focus in some schools on linguistic comprehension. According to researchers, the proportion of children beginning school with speech, language and communication needs is estimated at between 7 and 20 per cent (McKean, 2017) and unfortunately, communication issues carry a risk of low self-esteem and problems with self-confidence (Dockerall et al., 2017).

In the Gough & Tunmer model, the term ‘product of’ seems a little vague. I like to think that ‘product of’ refers to the flexible quality found in skilled reading as well as the dynamic integration of natural language with the alphabetic code. At first, beginning readers struggle to accommodate words and sentences of a variety of shapes and lengths, but as they become more skilled, they ease into a state of flexible, responsive reading, which leads to being able to read sentences whilst processing meaning at the same time. What is even more remarkable about this process is that reading with this wonderful flexibility takes place within distinct time constraints.

The time constraints are a kind of rhythmic signature for language comprehension as well as music and are biologically determined (Long, 2006). Each and every line of a song, poem or musical phrase typically lasts for 3-5 seconds. This brief ‘window’ is our subjective sense of the present moment (Gerstner & Fazio, 1995). In a song, a poem or a musical phrase, this moment is packed with messages and meanings – relating information about feeling, being or doing. The rhythm of reading in any language is very flexible indeed, but it is underpinned by this constant ebb and flow of units of meaning every 3-5 seconds. Becoming aligned with this natural flow of meaning helps children to read words, phrases and sentences with ease, fluency and understanding and also to anticipate words and phrases prior to reading them.

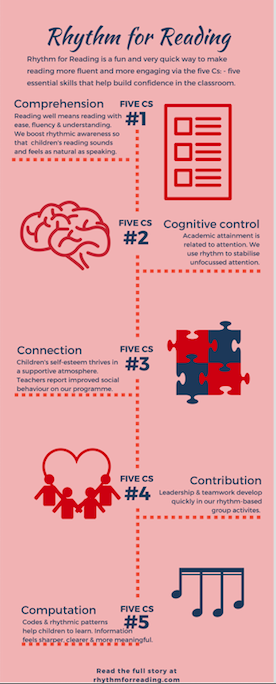

The importance of this rhythmic ebb and flow of meaning cannot be overstated and is a core part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. The programme uses music rather than words to develop rhythmic sensitivity, so it is suitable for children and young people who need a sharp ‘boost’ in reading comprehension, language and communication skills, phonological awareness or cognitive control, whether attending mainstream or special schools.

Barton, G “Teachers should encourage pupils to speak up – and should remember to do so themselves TES News https://www.tes.com/news/teachers-should-encourage-students-speak-and-remember-do-so-themselves Retrieved on 29.4.2018

Dockrell, Julie Elizabeth, et al. “Children with Speech Language and Communication Needs in England: Challenges for Practice.” Frontiers in Education. Vol. 2. Frontiers, 2017.

Gerstner, Geoffrey E., and Victoria A. Fazio. “Evidence of a universal perceptual unit in mammals.” Ethology 101.2 (1995): 89-100.

Gough, Philip B., and William E. Tunmer. “Decoding, reading, and reading disability.” Remedial and special education 7.1 (1986): 6-10.

Long, M. “Stamping, clapping and chanting: An ancient learning pathway?” Educate Journal, 3, 1, (2006) 11-25

McKean, Cristina, et al. “Language Outcomes at 7 Years: Early Predictors and Co-Occurring Difficulties.” Pediatrics(2017): e20161684.

Tags:

Do you have any feedback on this blog post? Email or tweet us.