Why empathy boosts reading comprehension in primary schools

23 February 2024

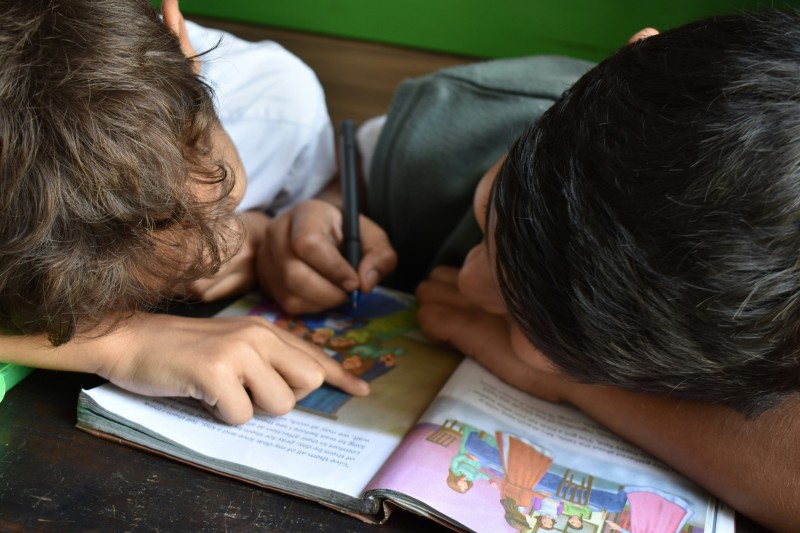

The importance of respect lies at the heart of school ethos and is the foundation for cooperative behaviour and positive attitudes towards learning. In practice, it is possible to cultivate these positive attitudes deliberately, particularly in early reading development if sufficient empathy and sensitivity exists. This means acknowledging cultural diversity - both in depth and breadth, and recognising the linguistic richness of the school community.

Confidence in learning is one of the greatest gifts that education can offer children, but this too requires empathy. Advantaged children start school socially well-adjusted and ready to learn, whereas disadvantaged children lag behind their classmates in this respect. For example, effective teaching that models thinking and reasoning is essential for disadvantaged children, when their attainment is behind age expectation in early reading development. In this post I look at ways in which a focus on empathy breaches social disadvantage and boosts reading comprehension.

Empathy

Let us remind ourselves that the first relationship that infants have is critical to development, because it precedes their own character formation and the sense of self. The primary caregiver is usually the mother in the first weeks of life, but not always. These early weeks of engagement with the infant are thought to influence the child’s development based on two types of maternal caregiving: sensitivity and intrusiveness.These qualities exist at opposite ends of a continuum and there is a general consensus that if the primary caregiver is sensitive about one third of the time, then the child will be socially well-adjusted and attach securely to the mother-figure. Sensitivity refers to the mother’s ability to empathise with her child, to infer her child’s basic requirements, as well as to respond to the child’s need to be soothed or to engage playfully. Traditionally, mothers have responded to their infants’ needs and desires by singing to them, playing peek-a boo style games and reciting stories. The effects of these activities on the developing brain of the infant have been researched and may help us to understand how to support the young children who struggle with early reading when they start school.

Reading Comprehension

The effect of storytelling on the human brain was first reported in 2010 by Silbert and Hasson. The research used a brain scanner to record brain activity as each participant listened to a story. The findings showed, perhaps unsurprisingly that in the auditory areas responsible for processing sound, the brain waves tracked the voice of the person reading the story. However, language areas of the brain and the areas responsible for the sense of self and others, lagged behind the auditory areas. The authors thought that the meaning of the story was being shaped by these slower processes. Further research showed that inserting nonsense words into the story scrambled the areas of the brain, assumed to be involved in processing context and comprehension (Silbert and Hasson, 2010).

According to the well known Simple View of Reading Model (Gough and Tumner, 1986), two foundational skills: linguistic comprehension and decoding are essential for the development of reading comprehension. Decoding is complex: it involves sounding our letters (transforming graphemes into phonemes and syllables) and then blending these into words (Ehri 1995; 1998). Even though individual differences affect the development of decoding, researchers assert that ability in decoding is closely aligned with reading comprehension skill (Garcia and Cain, 2014).

However, individual differences in terms of control of working memory, control of inhibition and the ability to update and adapt with flexibility to the development of the text affect children’s reading comprehension and researchers now think that these abilities also account for the difficulties with decoding as well (Ober et al., 2019). How might teachers make use of this information in a classroom scenario?

Empathy and comprehension in child development

Imagine for a moment that two children have been playing together with a spaceship. The adult supervising them hears that one child has monopolised the toy and the other child is crying in protest. To contain the situation the adult acknowledges and describes the feelings of each child and invites the two children to:

- read one another’s feelings by looking at their facial expressions,

- ask why their friend is feeling this way,

- imagine how they could make this situation better, and

- figure out a way to share the spaceship.

These are important steps because the children then take on a deeper sense of responsibility for:

- self-regulating their own behaviour,

- monitoring their friend’s feelings as well as their own, and

- planning how they might play together to avoid this happening again.

Through playing together, under sensitive professional guidance, these children are able to develop important life skills such as cooperation, learning to adapt to each other’s feelings, as well as planning and executing joint actions in the moment.

It’s also important to recognise that many children do not receive nuanced guidance from adults. Investment in early years provision and training is vital to address the effects of an exponential rise in social and economic disadvantage, but also, sensitivity to culturally and linguistically diverse children for example of asylum seekers and refugees is just as important. Children and adolescents who receive empathic guidance from adults, would for example need to be trusted by the parents of those children, and need to be appropriately culturally and linguistically informed (Cain et al., 2020).

The most important attribute of empathy is that it involves one person being able to connect their personal experiences with those of another individual. Learning about empathy under sensitive adult guidance promotes the development of inhibitive control. Control of inhibition strengthens working memory. Stability and strength in working memory fosters flexibility in thinking. Each of these executive functions lays strong foundations for the development of inference, fluency, and comprehension in reading behaviour, as Maryanne Wolf says,

An enormously important influence on the development of reading comprehension in childhood is what happens after we remember, predict and infer: we feel, we identify, and in the process we understand more fully and can’t wait to turn the page. (Wolf, 2008, p.132)

The adaptive benefit of empathy

The social benefits of empathy are wide-ranging and in terms of human evolution, the ability to act collectively, maintain social bonds and close ties with others has most likely helped our forebears to envision and execute large scale plans for the benefit of a whole community. For example, collections of animal skeletons have led researchers to conclude that more than 20,000 years ago, parties of hunter gatherers had developed killing techniques, honed over generations to take advantage of the seasonal movement of horses. In one site in France, more than 30,000 wild horses were slaughtered, some were butchered, but many were killed unnecessarily and were left to rot (Fagan, 2010).

Humans are like other mammals in the way that we are able to synchronise and move together. When humans gather socially and dance together this behaviour fosters empathy and social cooperation (Huron, 2001;2003).

Indeed, these types of activities have been shown to enhance the development of empathy and school readiness in young children (Ritblatt et al., 2013; Kirschner and Tomasello, 2009;2010), children in primary school (Rabinowitch et al., 2013), and after only six weekly sessions of ten minutes of synchronised movement, entrained to background music, research findings showed significant improvements in reading comprehension and fluency (Long, 2014).

Bringing this back to empathy again, a large scale study involving 2914 children showed that the benefits of shared musical activity were associated with the development of inhibitory control and a reduction of behaviour issues, particularly among socially disadvantaged children (Alemán et al., 2017).

Summary

Our human brains are wired to be social. Our ancestors worked cooperatively and were able to read their environment and infer the seasonal movements of animals. They planned, coordinated and executed hunting plans with devastating precision. Our ability as modern humans to read printed language with fluency, ease and comprehension is perhaps the most advanced act of human social collaboration of all, as it allows us to receive an enormous volume of information from each other about challenges that face us as a global collective. To what extent are we willing to empathise, to infer, to plan and to work together for our common good in an era that demands we now find our common purpose and act upon it?

Why not read about case studies of the rhythm-based approach in schools? Then click here to find out more about the Rhythm for Reading Programme and discuss it with me in person.

If you have enjoyed the themes in this post keep reading.

Conversations and language development in early childhood

Spoken language plays a central role in learning. Parents, in talking to their children help them to find words to express, as much to themselves as to others, their needs, feelings and experiences.

‘As well as being a cognitive process, the learning of their mother tongue is also an interactive process. It takes the form of continued exchange of meanings between self and others. The act of meaning is a social act.’ (Halliday, 1975: 139-140)

Conversations, rhythmic awareness and the attainment gap

In their highly influential study of vocabulary development in the early years, Hart and Risley (1995) showed that parents in professional careers spoke 32 million more words to their children than did parents on welfare, accounting for the vocabulary and language gap at age 3 and the maths gap at age 10 between the children from different home backgrounds.

Mythical tales of abandonment, involving fear of the jaws of death followed by the joy of reunion are familiar themes in stories from all around the world. Sound is a primal medium of connection and communication via mid brain processes that are rapid, subjective, subtle and subconscious. Similarly, the telling of stories, the recitation of poems and songs are also examples of how auditory signals are woven together to communicate for example fear, distress and joyful reunion, or other emotions.

References

Alemán et al (2016) The effects of musical training on child development: A randomised trial of El System in Venezuela, Prevention Science, 18 (7), 865-878

Cain, M. et al (2019) Participatory music-making and well-being within immigrant cultural practice: Exploratory case studies in South East Queensland, Australia, Leisure Studies, 39 (1), 68-82

Ehri , L.C. (1995) Phases of development in learning to read words by sight. Journal of Research in Reading, 18 (2) 116-125

Ehri, L. C.(1998) Grapheme-phoneme knowledge is essential for learning to read words in English. In J.L. Metal & L.C. Ehri (Eds.), Word recognition in beginning literacy (pp.3-40). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Fagan, B. (2010) Cro-Magnon: How the ice age gave birth to the first modern humans, New York, Bloomsbury Press.

Frith, U. And Frith, I (2001) The biological basis of social interaction. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2001, 10, 151-155.

Gough, P.B. and Tumner, W.E. (1986) Decoding, Reading and Reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7 (1), 6-10

Huron, D. (2001) Is music and evolutionary adaptation? ANYAS, 930 (1), 43-61

Huron, D. (2006) Sweet anticipation. The MIT Press

Kirschner, S. & Tomasello, M. (2009) Joint drumming: Social context facilitates synchronisation in preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102 (3), 299-314

Kirschner, S. & Tomasello, M. (2010) Joint music-making promoted prosocial behaviour in 4-year old children. Evolution and Human Behaviour, 31 (5) 354-364

Long, M. (2014) ‘I can read further and there’s more meaning while I read.’: An exploratory stud investigating the impact of a rhythm-based music intervention on children’s reading. RSME, 36 (1) 107-124

Ober et al (2019) Distinguishing direct and indirect influences of executive functions on reading comprehension in adolescents. Reading psychology, 40 (6), 551-581.

Rabinovitch, T., Cross, I. and Bernard, P. (2013) Longterm musical group interaction has a positive effect on empathy in children. Psychology of Music, 41 (4) 484-498.

Ritblatt, S. et al (2013) Can music enhance school readiness socioemotional skills? Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 27 (3), 257-266.

Silbert, G.J. and Hasson, U. (2010) Speaker-listener neural coupling underlies successful communication. Proc. Nate Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14425-14430

Wolf, M, (2008) Proust and the Squid: The story and science of the reading brain, London, UK, Icon Books

Tags:

Do you have any feedback on this blog post? Email or tweet us.