The Rhythm for Reading blog

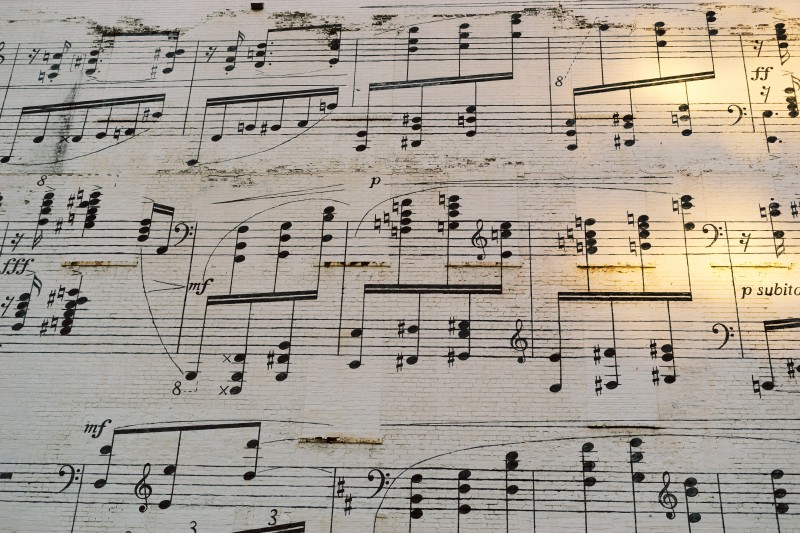

A simple view of reading - musical notation

18 October 2023

Many people think that reading musical notation is difficult. To be fair, many methods of teaching musical notation over-complicate an incredibly simple system. It’s not surprising that so many people believe musical notes are relics of the past and are happy to let them go - but isn’t this like saying books are out of date and that reading literature is antiquated? In homes all around the world, parents of all nationalities can teach children as young as three to read musical notation, as this has for a very long time become an internationally standardised system. In many schools in all parts of the UK, I’ve taught children at risk of failing the phonics screening check to read simple musical notation fluently in ten minutes. There are distinct differences in my approach and I’m sharing these here.

What is musical notation?

Musicians refer to musical notation as ‘the dots’!

These little marks written on five lines show musicians not only the musical details, but also the bigger picture - they can see the character and the style of the music by the way ’the dots’ are grouped together. Imagine you are looking at a map of your local area - you’d be able to see where buildings and streets are more densely or sparsely grouped together.

This is the skill that musicians use when they look at a page of music - it’s simply a convention for mapping musical sounds.

When was the first music written down?

Early evidence of this practice of notating music can be traced back to its archaic roots in Homer (8th century B.C.E.) Terpander of Lesbos (c. 675 B.C.E.) and Pindar (5th century B.C.E.). However, following the fall of Athens in the 5th century B.C.E., there was a break with tradition. Aristoxenus (c.320 B.C.E..) documented the cultural revolution that had taken place - the rejection of all traditional classical forms. Traditional music had been replaced by -

- a preference for sound effects imitating nature

- free improvisation

- a new fashion for lavishly embellished singing

The rejection of the old ways, including the ‘old music’ appeared to allow space for a new level of freedom. The new emphasis on individual expression rejected:

- traditional tuning systems and forms of both music and poetry

- being part of something greater than oneself

- creating something that would endure.

Musical notation, as the history shows, is less related to individual expression and more to the concept of building a musical canon - a collection of forms, styles and conventions, which are best represented in certain iconic ‘classical’ works. As such, there’s an emphasis on a standardisation of musical language, one that is mathematically well-proportioned, enduring and able to be passed on from generation to generation.

The most ancient system of musical notation, ‘neumes’ in ‘sacred western music’ was used between the 8th and 14th centuries, (C.E.) and was built upon Greek terminology. Most interestingly, the use of the apostrophe /‘/ ‘aspirate’ in the ‘neumes’ survives in today’s musical notation and shows when a musician takes a new breath or makes a slight pause. Part of the standardisation of musical notation has been that it is written on five lines.

What are the five lines called?

These lines, called ‘the stave’, show musicians whether the sounds are higher or lower in frequency (pitch). To take an extreme example, the squeak of a mouse is a high frequency sound (high pitch), and to show this frequency, the dots would be written far above the stave. Conversely, the rumble of a lorry has a low frequency sound (low pitch); to map this sound accurately, the dots would be written far below the stave. Extending the stave in this way involves writing what musicians call ‘ledger lines’.

In a central position within the spectrum of these very high and very low pitched frequencies, we have the pitch range of the human voice. Consider the sounds of the lowest male voice and the highest female voice and it’s clear that the spectrum of frequencies is still very wide. To accommodate this broad range of sounds, musicians write a different ‘clef’ sign at the extreme left of the stave. There are four ‘clef’ signs in common use: the treble (named after the unbroken boys’ voice), alto, tenor and the bass; these clefs are used by singers and instrumentalists alike. The two most commonly used are the bass and treble clefs.

- The bass clef indicates that the pitch range is suited to lower frequency sounds, matching the range of broken male voices.

- The treble clef at the extreme left of the stave indicates that the pitch range matches that of children’s and female voices.

What is the line between the notes called?

In the early 1600s, for reasons of clearer musical organisation, vertical lines started to appear in notation, which divided the music into ‘bars’ (UK) or ‘measures’ (US). For the most part, the number of beats is standardised in each bar. Keep reading to find out more about the beats!

Many of the most catchy pieces of Western music rely on simple repetition of short patterns as well as predictable beats. We perceive these to fall naturally into a regular grouping, and most melodies fall into a pattern of two, three or four beats, spread across the piece or song. Here are two recognisable examples, the first in three time, the second in four time:

- God save the King (UK) or God Bless America (US)

- Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.

Of course, we all know music that’s more complex than this. For example, traditional dance styles from all around the world are often more elaborate and combine rhythmic groupings of faster-paced patterns such as:

- 2s with 3s

- 4s with 3s

- 4s with 5s

Although these occasionally appeared in iconic classical works of the 19th century such as Mussorgsky’s ‘Pictures at an Exhibition,’ and Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, they became more commonplace in the early 20th century. These slightly irregular groupings create subtle feelings of asymmetry that is as delightful to the ear as new taste sensations are to the palette.

If there are five beats, as in ‘Take Five’ by Dave Brubeck, then after each group of five beats a vertical line shows the end of the ‘measure’ (US) also known as the ‘barline’ (UK). The bars or measures are units of time that show the organisation of the beats in the music.

Generally, ‘the dots’ and rhythms show the structure of a piece, or how it ‘works’ musically. In performance, a musician would maintain a consistent rhythmic ‘feel’. So these two essential notational elements offer a framework of predictability, which the musician reads, understands and feels:

- the number of beats in each bar

- the grouping and rhythm of the beats and notes within these bars

However, too much emphasis on the predictability and the vertical organisation of the beats can produce an effect that is wooden and robotic. Although a strict sense of rhythm and pulse (the beat) is essential for successful music making, the actual phrasing of these is more horizontal and somewhat elastic in feel.

This can work by making more of the musical tension, by stretching it in time and intensity, as well as making it louder and moving forward; it can help the listener wait in anticipation for the all-important climax and moment of release. This is incredibly effective at all levels of music making, and is known to us all in the more familiar context of telling jokes and stories, where the pacing is as important as the details.

So, this is why experienced musicians use ‘the dots’ only as a map, and allow their ‘feel’ for the rhythm, the harmony and the style to bring freedom and individuality to their expression.

What are ‘heads’ and ‘stems’?

The anatomy of ‘the dots’ tells musicians about the pitch and the time values of sounds they make.

The ‘heads’ are the oval shaped part of a note, whereas the ‘stem’ is the line that may be attached to the ‘head’. The ‘head’ of the note moves around on the stave and tells the musician about pitch and depending on whether it’s filled (black) or open (white), about time value. The ‘stem’ of the note can join with other ‘stems’ (called ‘beaming’) and tells the musician about time and emphasis.

Some teachers of musical notation are very ‘head’ focussed and have elaborate mnemonics for memorising the positions of ‘the dots’ on the stave. Here are some examples:

- All Cows Eat Grass (the spaces of the bass clef - A,C,E,G)

- Good Boys Deserve Fun Always (the lines of the bass clef - G,B,D,F,A)

- FACE (the spaces of the treble clef - F,A,C,E)

- Every Good Boy Deserves Food (the lines of the table clef - E,G,B,D,F)

The major problem with this approach is that it involves cognitive loading, as remembering these patterns rapidly absorbs a child’s finite cognitive resources. As a prerequisite for learning to read notation, these mnemonic patterns must be memorised and then applied in real time. Although this approach is not difficult for pupils with a strong working memory, it is absolutely why reading musical notation has gained its reputation for being ‘too difficult’ for some children to engage with.

Some leading musical education programmes in use today, are very ‘stem’ focussed and have elaborate time names for longer and shorter durations: ‘ta’ ‘ti-ti’ ‘tiri-tiri’ and ‘too’. Or, ‘Ta-ah’ ‘Ta’ ‘Ta-Te’ ‘Tafa-Tefe’ and there are many more to choose from.

The issue here is that the sound names are confusable because they sound so similar. Children with specific learning difficulties are likely to conflate these, and experience rhythm as confusing. This is unnecessary and easily avoided. Furthermore, it places children with weak working memory and weak sensitivity to phonemes at a considerable disadvantage.

We have completely avoided these issues in Rhythm for Reading and have opted for something simpler that does not front-load children’s attentional resources. In addition, our approach allows reading fluency to develop in the very first session.

We use simple and familiar language. ‘The dots’ are compared with lollipops and described as ‘blobs’ and ‘sticks’. Time names ‘ta’ and ‘ti-ti’ are simplified as ‘long’ and ‘quick quick’. There’s no confusion. This allows us to get on with the business of reading - fluently.

We offer professional development (CPD) that is deeply rooted in neuroscience, the development of executive function and of course, cognitive load theory. You can find out more in the following links.

Fluency, phonics and musical notes: Presenting the sound with the symbol is as important in learning to read musical notation, as it is in phoneme-grapheme correspondence. Fluent reading for all children is our main teaching goal.

Musical notation, full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection: Discover the back story… the beginning of Rhythm for Reading - an approach that was first developed to support children with weak executive control.

Empowering children to read music fluently: The ‘tried and tested’ method of adapting musical notation for children who struggle to process information is astonishingly, to add more markings to the page. Rhythm for Reading offers a simple solution that allows all children to read ‘the dots’ fluently, even in the first ten minute session.

How we can support mental health challenges of school children?

11 October 2023

The waiting lists for local child and adolescent mental health services- ‘CAMHS’ are getting longer and longer. Teachers and parents are left fielding the mental health crisis, while the suffering of afflicted children and adolescents deepens with every day that passes. Young people’s mental health challenges cannot be left to fester, as they affect their identity, educational outcomes, parental income and resilience within the wider community. Here are 10 key strategies that parents and teachers can use to support children and adolescents dealing with distressing symptoms of mental health challenges while they are waiting for professional help.

1. A calm educational environment

The size of the school seems to determine the quality of the learning environment to some extent. If every class takes place in a tranquil atmosphere, this means that every teacher takes responsibility for the ambience in every lesson. In ‘creative’ subjects such as music, art and drama, it is particularly vital that children participate in lessons where respect both for learning and for every student is maintained. An ethos of respect for every student is easier to sustain in a calm atmosphere. Children with mental health challenges are more likely to cope for longer in this setting, where they are better able to self-regulate any difficult feelings that may arise.

2. A space to talk

In a school it is important that teachers and children have spaces where they are able to discuss and resolve pastoral or academic challenges in privacy, rather than for example, in the middle of a busy corridor. This is incredibly important for the more vulnerable pupils in our communities. Those with special educational needs and disabilities need to be supported with a particular focus in terms of social, emotional and mental health. A place where children are able to ask for help or advice from the pastoral team immediately shows all pupils that this is a caring school that values their feelings, responds to their questions and most importantly, takes their mental health challenges seriously.

3. Listening from the heart

The pressure of workload on teachers is enormous, and yet according to research, teachers are more effective in the classroom when they not only show their passion for the subject, but also that they care deeply about the children they are teaching. Both these factors unfortunately can lead to teacher burn-out, which would obviously diminish their capacity to listen from the heart.

Arlie Hoschild’s ’The Managed Heart,’ discusses ‘emotional work’ as an integral but undervalued and unrecognised aspect of many public-facing roles.

Teaching is clearly one these, requiring intense and constant emotional input. Sadly, many of the best and most dedicated teachers suffer because they are so invested in pupils’ learning and personal development.

It is vital that school leaders cultivate an environment that values the well-being of teachers, protects them from abuse, prevents them from burning out and avoids unnecessary workload. Teaching can be incredibly fulfilling, but often feels all-consuming. It is therefore vital that teachers have realistic and sustainable workloads. Our teachers deserve to have time to recharge during the school day so that they are better able to support pupils’ mental health challenges, particularly if they work as part of a pastoral team.

4. Compassionate reassurance

Much has been said about empathy in recent years, but compassionate reassurance achieves a stronger outcome in less time. Compassion involves complete acceptance of the situation, as well as the capacity to hold all the challenges of that situation in mind, which is why it is easier to help students to feel emotionally ‘safe’, as they are more likely to begin to self-regulate. This involves being able to breathe deeply and slowly, feel physically more relaxed and more connected to their body, which may enable them to be better able to express their feelings and to share their concerns more openly.

5. Offering quality time with no distractions

Imagine a nine year old child, overwhelmed by a challenging situation and dealing with a mental health challenge, such as acute anxiety. One day, they feel ready to trust a teacher, to open up and to disclose their concern, but to their disappointment, the teacher must rush away to deal with something rather ‘more urgent’.

Their rational response would say, ‘Yes, emergencies happen, but my feelings are not as important as an emergency.”

At the same time, their vulnerable feelings might achieve a ‘shut down’ in their central nervous system and a dread of abandonment or rejection could trigger an acute attack of panic or anxiety or other distressing feelings and thoughts.

It is important for the child that the teacher stays physically present with them until that conversation or connection has reached a mutually agreed end point. If not, a negative spiral can quickly gain momentum if the ‘end’ of the conversation or connection feels abrupt or unplanned.

6. Practising gentle kindness

In day to day life, if we practise gentle kindness, it is obvious that we are not interested in conversations that are unkind. By walking away, we are showing that unkind remarks are not taken seriously. Gentle kindness begins in the mind, replacing judgmental thoughts with compassionate ones. It is arguably far easier to prevent mental health challenges than to treat them. Gentle kindness is a strong starting point for effective prevention.

7. Honouring the feelings

We all have feelings. Most people are uncomfortable with accepting all their feelings because difficult emotions such as shame or guilt or a belief that they are ‘not enough’ are pushed under the rug and barely acknowledged in our society.

Children and young people make comparisons between themselves and an ‘ideal’ version that they have seen online or experienced through parental scripting.

Here are a few examples of parental scripts or expectations of their child:

- To get married and have children

- To support the same sports teams as their parents

- To attend a certain school or university

- To take on the family business or join a certain profession

- To live in a particular geographical area

Sometimes this form of scripting is very ambitious and the child is expected to achieve one or several of these:

- To qualify to represent their country in an elite sports team or even in the Olympics,

- To win a scholarship to a particular school or university

- To have top quality examination results

- To break records or ‘be the first’

- To become so special and so talented that they are recognised for their accomplishments.

If these expectations are not fulfilled, harsh self-judgments and self-criticisms are likely to follow.

All of these negative beliefs, thoughts and feelings may well become so toxic that they may have a detrimental effect on the individual.

Conversely, a child who has too little support or stimulus from their family may well feel neglected and frustrated by a lack of attention and display challenging and self-pitying behaviour.

It is important to protect children from creating idealised versions of themselves. Even conscientiousness, which is often encouraged at school and is intrinsically admirable rather than harmful, can develop into an unhealthy source of anxiety and low-self-worth in certain situations.

8. Expressing the emotions

To express anger, frustration or resentment appropriately is natural and necessary. An outlet for emotions can be through sport or dancing or even music and singing. Some writers claim that anger has fuelled their best work! The response to these emotions has been carefully honed by warrior disciplines where the balance of managing and harnessing energy is the product of many years of dedicated training - for example Samuri warriors who are taught not only combative skills but also flower arranging. Cultures all around the world have found different ways to manage and express emotion in a socially accepted way. All of these practices involve allowing the body to discharge the emotions, as this is healthy.

Insufficient access to the creative curriculum means that pupils are restricted in terms of self-expression, the development of executive function, personal development and critical thinking. One appropriate way to express emotion is to dance and move, or sing and play music, allowing the body to cast off all the explosive, the aggressive and fiery feelings. Another way is to write down how these emotions feel and to really vent this on the page. These forms of physical release are very cathartic, though this needs to be done in a place, ideally out in nature - or where others won’t be disturbed!

9. Sharing worries and concerns

Young people and their parents need to share their challenges, worries and concerns. If a young person’s mental health challenges start to spiral and the situation deteriorates suddenly, this needs a swift and orchestrated response from everyone with a duty of care. It is not enough just to prioritise the children’s development of topical concepts such as, ‘resilience’, ‘growth mindset’ and ‘perseverance’. Above all, young people should not be left feeling isolated and surrounded by adults who are uncertain about what they ought to do, when facing a child who feels seriously overwhelmed, depressed or anxious.

Charities run helplines, manned by volunteers, and they train their people to offer a compassionate listening service. No one needs to suffer in isolation while they wait for professional help. As well as pastoral teams and family liaison workers in schools, there are helpline volunteers who work for charities that exist outside school. Together we can make sure that we support the families coping with child and adolescent mental health challenges every day.

10. Helpline numbers

Family Lives: 0808 800 2222

The Samaritans: 116 123

Childline: 0800 1111

NSPCC: 0808 800 5000

In an emergency dial 999.

Did some of this post resonate with your own experience?

If so, you might be interested in the important role played by rhythm in the management of stress in these related blog posts:

Education for social justice - This post sets out the mission, values and impact of the Rhythm for Reading programme in terms of reading and learning behaviour.

Rhythm, breath and well-being - This post unpacks the relationship between rhythm, breath and well-being in the context of smaller and larger units of sound, comparing the different types of breath used in individual letter names versus phrases.

Releasing resistance to reading - Discover how self-sabotaging behaviour and resistance to reading can be addressed through a rhythm-based approach.

Rhythmic elements in reading: from fluency to flow - Discover the importance of rhythm in activities that involve flow states and the way that elements of rhythm underpin flow states in fluent reading.

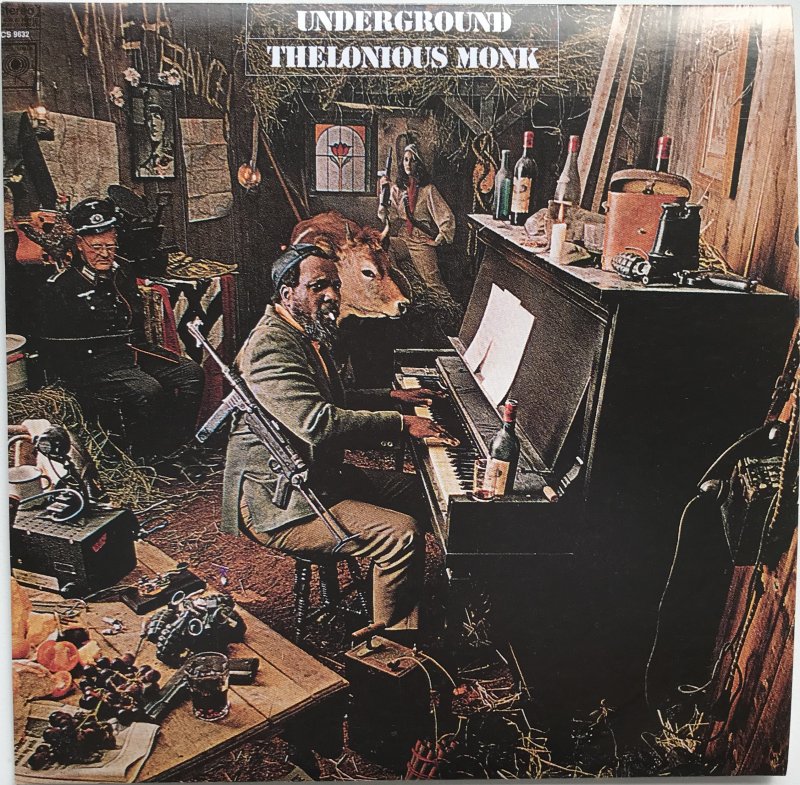

Thelonius Monk (1917-1982) A personal tribute

4 October 2023

Black History Month invites us to celebrate our differences more than ever. A knowledge-rich curriculum offers big ideas and invaluable depth of insight, but the creativity of Monk shows how knowledge can be developed to pioneer new forms and techniques. His music is unmatched in its capacity to inspire people of all ages because of its originality, which is preserved in the recordings. We are very fortunate indeed to be able to hear the playing and ideas of a musician who has led the development of an entire genre.

Having been hugely inspired by Thelonius Monk’s music, artistry and originality, I am going to express my appreciation for this exquisite musician here even though it’s impossible to do full justice to this musical icon through words alone. As a musician he is one of a kind - therefore this blog post will fall spectacularly short. But, as there is a huge gap between the struggles he endured during his lifetime and the huge amount of recognition that his artistry and humanity has received since his death, I’m going to highlight these contrasts here.

Back in the day…having graduated from the Royal Academy of Music in the late 1980s I was working with the superb musician, innovative pianist and inspirational composer, Roger Eno. I remember asking him about the artists he most deeply admired. Hearing Eno talking about Monk was so moving that I rushed out to buy a couple of albums - later that same day I listened closely to this giant of jazz.

A musician’s musician

Monk is truly a musicians’ musician. He inspires us to dig deeper and think bigger, to create with true integrity and honesty. There are forty-nine tribute albums made by admiring colleagues dating from 1958 right up to present times - the most recent was recorded in 2020. Posthumously, Monk has been awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1993), and the Pulitzer Prize (2006), but it wasn’t until 2009 that he was honoured by his home state in the North Carolina ‘Hall of Fame’.

My own first impressions, hearing this genius for the first time were a mixture of the deepest gratitude for his sincerity, and delighted astonishment in his freedom, playfulness and wit. There are other musicians who can match Monk’s dazzling piano technique - but what sets Monk apart for me, is that he took his mastery of the piano to a level of creativity that was utterly original.

Tenderness, wit and subversion

He used the piano to acknowledge tenderness, to dismantle and reweave others’ works and he delightfully subverted iconic works by other composers.Take for example, ‘Criss-Cross’ - in this track, Monk mocks Stravinsky’s ballet, ‘The Rite of Spring’ and we hear the saxophone and the piano calling out the famous opening motif played by the solo bassoon. Later Stravinsky’s ‘primal’ cross rhythms emerge through the composition, repurposed by Monk to restore percussive vibrancy to the nuanced rhythmic feel of these patterns.

Even more vivid perhaps, is ‘North of Sunset’. This track nods to the traditional blues which appear and disappear fleetingly, like shadowy outcasts in the glare of Monk’s quirky grammatical purity and the lean contours of his modern jazz style.

Architecture and musical form

Then there’s Monk’s relationship with depth and perspective. The best musical compositions of any genre have an architectural quality, with clearly defined form and proportions unfolding through sound. And yet in Monk we hear musical structures projected with the clarity of a hologram. For instance in the track, ‘Between the devil and the deep blue sea’ (based on Harold Arlen’s work of 1931) there’s infinite perfection in the proportions. Monk matches structural precision with a vivid portrayal of the title. At the end of his solo, he pushes the music over the edge and into vertiginous cascades of notes, shaking up our depth perception. Then there’s a curious restlessness that smoulders and smokes, depicting the title of the track perfectly.

Mimicry and magic

Other tracks that come to mind with a similarly dazzling precision are ‘Locomotive’ in which the breadth of the ‘groove’ evokes a driving mechanical feel, punctuated by crunchy chordal edginess. ‘Tea for Two’ is joyful in a suitably restrained and respectful way, but then unexpectedly explodes into a delightful sound world, mimicking the clatter of porcelain teacups and saucers. Elsewhere there are fleeting references to Schubert’s ‘Trout’ Quintet, with Monk conjuring witty and magical surprises.

Contemplative mood

It’s not all about wit and clever jokes. One of the things I most admire most about Monk as a performing artist is his use of space and silence. In ‘Japanese Folk Song’ the lyrical melody is stripped back to an emaciated dry skeleton, devoid of unnecessary or extra sounds and yet this transformation makes it all the more potent. Sharing with us the nakedness of the folk song, he displays his extraordinary gift for working with the essence of melody and the spaces between notes - in this case the chasms between chords, which achieve alchemy in real time.

In these tracks he shows his powers in dismantling a melody, a musical style, and a genre, then rebuilding it, but with the precision of a watchmaker whose fingers were immediately able to align the sound with whatever his mind envisioned.

Creativity flowing from ambiguous moments

After my own thoroughly classical training, encountering the exuberance of his playing reminded me what music was really for and how our creativity is the most authentic gift humans can offer to one other. For an illustration of this, in ‘We See,’ the abrupt musical fissures in the seemingly conventional introduction metamorphose into an extraordinary spaciousness. We soon discover that this ambiguity is the precursor, the necessary foundation from which a richer harmonic language emerges. Complementing the depth and complexity of the harmonies, we hear Monk’s ability to stretch and mould the elasticity of cross-rhythms and lilting flexibility of the phrases. Monk was always searching for the edges of extremes within the logic of balance, but in this track he appears to explore the boundaries of what’s possible in a more playful and yet still profound way.

Necessity as the mother of invention

When researching this post, I was sad to read about his struggles in life. He had even endured being beaten and unlawfully detained by the police. In every setback he displayed resilience and dignity. Surely the sophistication of his playing developed in part from sheer necessity: he had to create this unique style so that his music became his intellectual property - it was essentially impossible to copy. Listening to the melody in Monk’s ‘Bolivar Blues’ however, the ‘hit’ theme song ‘Cruella De Vil’ from Disney’s ‘1001 Dalmatians’ clearly shows more than a ‘homage’ to Monk. And he didn’t receive the full recognition that he deserved during his lifetime. Had Monk been awarded the Grammy and the Pulitzer while still alive, I would like to think that he’d have played more in the later years of his life and suffered fewer mental health issues.

Outcast or Genius?

Just as most books about reading development don’t mention rhythm, books about music tend not to mention Monk. But, Steven Pinker in ‘How the Mind Works’, is unequivocal under the heading ‘Eureka!’

And what about the genius? How can natural selection explain a Shakespeare, a Mozart, an Einstein, an Abdul-Jabbar? How would Jane Austen, Vincent van Gogh, or Thelonius Monk have earned their keep on the Pleistocene savannah?

Here’s part of Pinker’s brilliant answer to his own question:

But creative geniuses are distinguished not just by their extraordinary works, but by their extraordinary way of working; they are not supposed to think like you and me.

If you enjoyed reading about this giant of jazz, here are links to related posts about the value of music and creative subjects in the curriculum - (with a light touch of political opinion). As Brian Sutton-Smith once said,

The opposite of play is not work. The opposite of play is depression.

Creativity, constraints and accountability - Creativity is hardwired within all of us and there’s a playfulness in the ‘what if…’ process which guides an unfolding of impulse, logic and design.

The Power of Music – This post discusses Professor Sue Hallam’s ‘Power of Music’ - a document that reviews more than 600 scholarly publications on the effect of music on literacy, numeracy, personal and social skills to support the need for of music in the education of every child.

Knowledge, culture and control - Is history cyclical? As we move rapidly into climate crisis, artificial intelligence (AI) and a school curriculum dominated by STEM subjects, this post questions the present lack of emphasis on critical thinking and creativity.

Reading comprehension: How to stay connected with the text.

27 September 2023

In early reading, children must use their ears, eyes and voices in a very focused way. Their attention, already scanning everything that moves in the environment around them must suddenly narrow down onto a page, an illustration and then onto the tiny squiggles of black ink that they are learning to decode and understand. Many children willingly take on the challenges of reading. Some learn to read effortlessly, but what about those children who cannot focus their eyes and ears and voices onto the page? Read on to discover how to support all learners, particularly the most disadvantaged and those with SEND, as every child needs to connect deeply with reading in order to access the curriculum. If, like me, you are passionate about helping every child to access the curriculum and to overcome their challenges with connecting to the text, click the link to get the FREE downloadable pdf checklist.

What does connected to the text mean?

When writers convey messages through words, their readers receive those messages. For the development of reading comprehension, connections with the text should have been made between:

- the writer and the reader,

- the writer and the words,

- the reader and the words.

The words are the ‘messengers’ that provide the link between the writer and reader. Even though communicating through written language is complex, as it involves knowledge and skill, it is also an important form of social connection that people use every day of their lives. Reading with fluency and understanding therefore builds a child’s resilience, confidence and independence. Until the invention of the telegraph, people wrote letters to each other when they needed to convey an important message. Emails have replaced letters to a large extent, but reading comprehension is important for understanding many different forms of written language such as:

- text messages

- emails

- letters

- news articles

- stories

- non fiction books

- websites

How many types of connection are there between the writer, the text and the reader?

According to Keene and Zimmerman’s book, ‘Mosaic of Thought: Teaching Comprehension in a Reader’s Workshop’, published 25 years ago, there are three main levels of connection and these make the text more relatable and meaningful to the reader.

- text-to-text connections

- text-to-self connections

- text-to-world connections

Text to text connections allow the reader to grasp the style of language being used, which may be formal and using jargon, or informal and using everyday language. Reading a wide range of different texts helps readers to adapt to a variety of styles of language use, and also supports fluency and comprehension.

For example, the first time someone reads an official letter from an authority, the formality of the tone, and the use of unfamiliar words and phrases might be off-putting. However, when a similar letter arrives one month later, it’s easier to make connections with the underlying message, because the reader has already adapted to this particular writing style, with its ‘professional’ tone and use of formal language. This is one example of how text-to-text connection speeds up the process of understanding the message conveyed by the official letter.

Text-to-text connections also allow the reader to pick up the structure of a story. For instance, when a reader returns to a novel and starts reading a new chapter, there is a sudden recollection of the plot and characters from earlier chapters. Text-to-text connections are made as soon as the information from the earlier chapters of the book spontaneously arrive in the reader’s mind and provide the background information for a deeper and more satisfying understanding of the new chapter.

Text-to-self connections enable a reader to feel personally invested in a narrative. This might happen because the details in the text are similar to the reader’s own day-to-day, or perhaps even their imaginary life. How many children wish that they could fly and then feel connected to their favourite superhero? Even more importantly, some children may discover lifelong fascinations or passions through making text-to-self connections during reading.

Text-to-self connections also make the text believable. Even if the book is futuristic and seems unreal in many ways, human experiences such as danger, love, hunger and even boredom can spark text-to-self connections.

Text-to-world connections provide the reader with a sense of time, place and context. For example, many of the Rosie and Jim stories start with ‘One sunny day….’ which would always be followed by a description of where in the world Rosie and Jim were, as well as why they were there. Even very young children can discuss these text-to-world connections when parents are reading to them.

Both older and younger children can benefit from text-to-world connections by linking new to existing knowledge. This opens up into a powerful learning pathway because the children experience reading as rewarding and intrinsically motivating, which is why many develop a thirst for learning.

Text-to-world connections also show the reader how things work.Take for instance, the difference between rubber balloons that children can blow into, versus helium balloons or even hot air balloons. In a text about these different types of balloons, the reader might already have a text-to-world connection, as well as a self-to-text connection about ordinary ‘birthday party’ balloons that can be inflated at home. The reader’s text-to-world connection expands very quickly as they learn that helium balloons contain a gas that is lighter than air, and that this gas causes the helium balloon to disappear up into the clouds if released into the air outside. The text-to-world connection develops even further as the child reads that large hot air balloons work by heating the air with a controlled flame to make it rise to such an extent that it can carry people in a basket below.

How can I support reading comprehension through these connections?

In early reading there are many different ways to support the development of reading comprehension, such as taking turns to read aloud, talking about what was read, extending vocabulary by introducing new words in context and drawing attention to different letters and sounds.

Here are some effective ways in which adults can support children’s early reading before, during and after the reading activity.

Before reading the text, ask questions about the title, the author and the book’s cover. Help the child to think about similar texts they may have come across - perhaps by the same author or on the same topic or featuring the same character. The illustration is likely to show the context for the story and this is similar to something the child may have already experienced.

During reading, check with the child that they are making connections with the text. Help them to monitor the messages in the text by discussing the meanings of key words and probe their text-to-self connections by asking them how they may feel in a similar situation.

After reading, ask the child further questions about the text to help them find deeper connections with their understanding of the setting. This may involve talking about the characters’ intentions and feelings and what might happen in the next chapter. They may even want to think about an alternative ending.

What are word choices?

Word choices are the child’s solution to decoding - the words that ‘best fit’ the relationships between letters and sounds, the context and the grammatical structure of the sentence.

When a child is connected to the text, word choices are made more quickly and effectively. So a ‘text-to-world’ connection would allow a child to select ‘circus’ rather than ‘circle’, especially if the main characters in the story were, for example, acrobats.

Word choices based on connections to the text are also informed by the development of the text. Using likelihood to make word choices, based on connection to the text, is very different to a fundamental strategy of guesswork, in which children are usually correct between ten and twenty per cent of the time.

What is prior knowledge?

Prior knowledge is what the child already knows before reading the text. Prior knowledge develops every day of our lives and is more easily accessed when we feel relaxed and yet alert.

Children pick up prior knowledge through conversations as well as through media such as books, television, games and the lyrics of songs.

Even if a child has never been to the circus, they may have seen one on television, heard about another child’s visit, or even sung the song about ‘Nelly the Elephant’ (who belonged to a travelling circus).

What are the main things to consider in relation to reading comprehension?

Here are some tips, if a child makes an inappropriate word choice:

- It’s a good idea to stop reading and talk with the child about their connection with the text.

- It’s unhelpful to say, “That’s nearly right”. Instead, say, “Hang on a moment! Let’s think this through”.

If you notice that the child frequently misses the ends of words, (also known as ‘suffixes’), this does not mean they are being careless! It means they are not processing the deeper grammatical structures of the text and may need support through a reading intervention that deepens their level of engagement.

Please see below where I’ve linked to related blog posts for further information about this.

Did you enjoy reading about the different types of connection that support children’s reading comprehension?

Would you like to put these ideas into practice?

Then, click here to get a FREE Reading Comprehension checklist.

Here are links to related posts about the deeper levels of language comprehension.

Visiting the library for the very first time - Share in the joy of a ten year old who has just discovered that reading is meaningful!

Virtuous spirals - This is a brief look at the differences between skilled and unskilled readers.

Ears, eyes and voices - This explores early reading and the importance of speech perception and the arcticulatory system.

Reading fluency: Reading, fast or slow?

20 September 2023

The smarter you get, the slower you read,

says Naval Ravikant - a leading investor in the world of tech giants.

Yes, an appetite for absorbing the detailed content of a piece of text does lead to slower and closer reading. In fact, fluent reading is likely to vary in pace depending on the style of the writing. It’s a bit like driving in traffic. For conditions that demand sharp focus and concentration, we slow our driving down. Likewise, when we have more favourable conditions, we can drive with greater ease and enjoy the journey more. But no matter what the conditions are like, we don’t become reckless. We don’t lose control of any part of the driving. Let’s discuss this in relation to early reading, the development of reading fluency, and how it is taught.

Is it better to read quickly or slowly?

The most proficient readers adapt their reading skills to match the text. In other words, being able to dial the reading speed up and down is a strong indicator of emerging reading fluency. Schools ensure that all children become confident fluent readers, so that every child can access a broad and balanced curriculum. Fluent reading underpins a love of reading and is an important skill for future learning and employment and it also enables children to apply their knowledge and skills with ease.

In the early reading phase, children learn to remember what they’ve been taught and to integrate new knowledge into larger concepts. In other words, children learn to coordinate different streams of information. This is a bit like learning to drive (for an adult), because many different elements need to be coordinated and practised until these become second nature - such as:

- selecting and operating either the brake or the gas pedal

- steering the vehicle smoothly

- communicating direction using the indicators

- anticipating the speed of travel

- aligning speed with changes involving gears and the clutch

- monitoring what other vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians are doing on the road.

Fluent readers can:

- read accurately and with appropriate stress and intonation

- coordinate different streams of information very easily

- access each channel of information with ease

- read quickly, but adjust the speed of reading to suit the challenges of each passage

- monitor the meaning of the passage as they read.

In early reading, children who approach reading fluency without undue effort have coordinated their eyes, ears and voices:

- to appraise cues from pictures accompanying the passage

- to apply short term memory in order to locate the information in the passage in terms of time and place (context),

- to recall general knowledge from long term memory of how things happen (schema)

- to recognise the shapes of letters (graphemes)

- to discern the smallest sounds of language (phonemes)

- to articulate the relationship between the letter shape and its sound.

- to decode the words and to assign the grammatical function of each word in the sentence

- to access the lexicon (a child’s ‘word bank’) in order to retrieve the most likely words to match the information on the page.

Some of these channels of information are processed subconsciously and therefore at lightning speed. For example, the child’s lexicon (word bank) supplies the word that is the best match to the information on the page. The streams of information that contribute to the retrieval of a certain word are:

- word shape,

- sounds associated with the letters,

- context in short term memory

- schema (background knowledge) in the mind of the child.

In the earliest stages of learning to read, as the child learns to processes information about letters and sounds, they do this relatively slowly and consciously, using the thinking part the brain. It’s important that children allow the knowledge that they acquire during phonics training to inform their recognition of words, because after a period of initial ramping up and practice, it’s vital that this skill becomes second nature and that the speed of processing rapidly accelerates.

Fluent readers can read quickly, accurately and with appropriate stress and intonation, which aids comprehension by freeing up cognitive resources sufficiently to focus on meaning. Therefore, after the children have achieved a secure knowledge of phonics, fluency becomes an increasingly important factor in the development of reading comprehension.

However, many children experience ‘bumps in the road’ when they’re learning to read. They may have some stronger and some weaker channels of information processing. If there are weaknesses in attention, phonological discrimination or visual discrimination, the child will not be able to coordinate the many different channels of information that contribute to fluent reading.

What is reading word-by-word?

Reading word-by-word typically occurs among the lowest 20% of children: those who most need to improve in their reading. They need to refresh their attention for each word, as even reading an individual word can absorb all of their focus and attention.

Their fluency will not develop alongside that of their classmates and they will fall behind unless they receive an early reading intervention. Some teachers of reading assume that the skill of segmenting and blending phonemes is necessary for reading fluency to develop.

Actually, many children remain stuck at the ‘sounding-out’ stage of reading and do not become fluent readers, even though they know the correspondence between letters and their sounds. For these children, it’s likely that their attention is weak, and they lack the cognitive control to coordinate the various streams of information processing that support reading fluency.

What is speed reading?

Speed reading is measured in terms of how many words a person can read in one minute. This is known as words per minute (wpm).

Speed reading has been associated with having a higher level of intelligence, because people who read quickly are thought to consume more information and therefore become smarter. This association between speed reading and intelligence has led some teachers of reading to believe that reading faster is necessary for the development of good reading.

If building reading fluency were this simple, children with fast reading speeds would not -

- make accuracy errors

- need to reread the text to answer comprehension questions.

Although speed reading might appear attractive as an idea, and it is likely that a good reader can read fast, reading fast in itself does not necessarily develop into good reading.

Conclusion

At the heart of this is a huge misconception:

If a child prioritises speed, they may learn to decode the print into words, phrases and sentences. But, they may not have engaged with the grammar of the text.

As discussed, encouraging a child to read for speed may do more harm than good. If a child is praised for reading fast, they are more likely to experience reading as unrewarding, boring, a waste of their time and pointless.

If a child is encouraged to slow down and to discuss what has happened in each sentence, they will engage with the text as meaningful, even if they struggle to read independently. This communicative approach shows the children that they are reading in order to learn. Therefore, interactions between an adult and a child that involve talking, reasoning and extending spoken vocabulary are highly valuable, and they have been found to have significant effects on the development of early reading.

When reading at home with their children, parents can easily adopt these communicative approaches. Reading aloud is a good way of developing vocabulary as well as expressive language skills. They might also encourage their child to notice punctuation, the development of the narrative and any dialogue in the text.

Click here to see the full list of reading fluency tips in the Reading with Fluency Checklist.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, and you’d like to find out even more about the development of reading fluency, keep reading….

Reading fluency and comprehension in 2020 - here I discuss the relationship between resilience and fluency in relation to reading speed.

Discover the heartbeat of reading- this post explores the importance of bringing the grammatical cues in reading into systemic alignment.

Rhythmic elements in reading: From fluency to flow - a flow state is associated with reading for pleasure and fluency is a key to unlocking a flow state.

Phonemes and syllables: How to teach a child to segment and blend words, when nothing seems to work

13 September 2023

There is no doubt that the foundation of a good education, with reading at its core, sets children up for later success. The importance of phonics is enshrined in education policy in England and lies at the heart of teaching children to become confident, fluent readers. However, young children are not naturally predisposed to hearing the smallest sounds of language (phonemes). Rather, they process speech as syllables strung together as meaningful phrases.

Phonemes are more difficult for some children to detect than syllables, and they particularly struggle with learning to read, as they are unable to detect the boundaries between individual words and syllables. Schools are expected to give all learners the knowledge and cultural capital they need to succeed in life and to pay special attention to the children who need to improve their reading (the lowest 20%).

Phonemic awareness and the ‘alphabetic principle’ need to be explicitly taught until they become automatic. And yet, unlocking stubborn barriers to phonemic awareness can take years, if relying upon conventional approaches. However, a simple solution - a segmenting and blending game, can support teacher effectiveness, thus enabling these children to access phonics teaching. And it can be used right from the start! This strategy may also protect them from falling behind their classmates. Read on to learn this playful approach and practise it with a FREE downloadable word list.

What is segmenting?

Segmenting is a skill that breaks sounds down, by drawing attention to them and allowing awareness of the smaller units of language to emerge. Words can be segmented into syllables, and syllables can be segmented into phonemes. Mastering this skill involves holding a word or a syllable in mind and then breaking it down into smaller sounds. Thus, a word such as ‘seashell’ can be initially segmented into two syllables, which are, ‘sea’ and ‘shell’.

Taking this to the next level in terms of detail, each syllable can be segmented into the smallest sounds of language, which are phonemes. There are two phonemes in ‘sea’, which are:

- the first sound /s/

- the vowel sound /ea/.

However, there are three phonemes in ‘shell’, and these are:

- the first sound, /sh/

- the vowel sound /e/

- the final sound /ll/.

So, if we take the word, ‘seashell’ as a whole, we have segmented the word into five phonemes, which are: /s/ea/sh/e/ll/.

Some phonics methods use ‘onset and rime’ to develop the skill of segmenting. This approach is designed to sharpen children’s sensitivity towards the boundaries within syllables, whilst retaining a sense of the syllable as an individual sound unit.

When teachers use the ‘onset and rime’ method, they segment a syllable into only two parts:

- its first sound, - (also known as the ‘onset’)

- all the remaining sounds, (which make up the ‘rime’).

Using onset and rime, ‘seashell’ would be taken syllable by syllable. Each syllable would be segmented into two parts.

- the ‘onset’ of ‘sea’ is /s/ and the ‘rime’ is /ea/.

- the ‘onset’ of ‘shell’ is /sh/ and the ‘rime’ is /ell/.

What is blending?

Blending is the skill that involves building words up, either from syllables, or individual phonemes.

What’s the difference between segmenting and blending?

There is one simple difference. Segmenting involves breaking a word down into smaller units of sound, whereas blending is a reversal of the process.

- The two syllables, ‘skate’ and ‘board’ can be blended together to make one word, ‘skateboard’.

- The phonemes, /c/a/t/ can be blended together to form the word ‘cat’.

- Using ‘onset and rime’ /b/ and /ell/ can be blended together to form the word ‘bell’.

Is it better to teach blending or segmenting first?

The two approaches can be taught side by side. Both segmenting and blending skills are necessary for decoding longer words and shorter words. Let’s take a shorter word, ‘then’.

‘Then’ using a purely phonemic strategy would be segmented as /th/en/ and these sounds, if blended together make the word ‘then’.

Teachers need to guard against a visual strategy (in which the reader has visually decoded ‘the’ as a familiar word that they recognise mainly by its shape) as it wastes a lot of time.

‘Then’ using a partly visual strategy would be segmented as /the/n/ and these sounds, if blended together could make a nonword that would almost rhyme with ‘fern’.

Children need to recognise that /th/ on its own is a phoneme that can be blended with many other sounds.

In the onset and rime approach, /th/ can be blended as follows:

- /th/ blended with /at/ makes ‘that’

- /th/ blended with /en/ makes ‘then’

- /th/ blended with /is/ makes ‘this’

- /th/ blended with /us/ makes ‘thus’.

What about longer words?

Let’s take a longer word such as ‘umbrella’- there are three syllables here and seven phonemes.

- A child skilled in phonics, would immediately sound out the individual sounds, /u/m/b/r/e/ll/a.

- A child skilled in ‘onset and rime’ would segment the word into syllables, /um/brel/la.

As this is a longer word, segmenting at the syllable level would be a more successful strategy. When a child segments at the phoneme level, each phoneme has equal emphasis. However, in the English language, longer words have unequal emphasis - with some syllables assigned a little more energy (in terms of intensity) vocal stress, and length (in terms of duration). IN the word ‘umbrella’, it is the second syllable that carries vocal stress.

Segmenting at the syllable level allows the child to hear more easily where the stress may fall in the word. The assignment of stress is very important for recognising a word and immediately understanding the meaning of the word in context. For example, the word ‘record’ carries the stress on the first syllable when it functions as a noun (first bullet point) and on the second syllable when it functions as a verb (second bullet point). The vowel /e/ is also subtly different.

- Here is a change to his hospital record.

- They record their music in a studio.

When segmenting and blending aren’t working

Communicative approaches such as drawing attention to letters and sounds in early reading, combined with teaching effectiveness are strong predictors of pupils’ progress throughout school. And yet, for some children, a weak working memory means that manipulating sounds in real time is difficult because attention fades, before the child has:

- understood the task,

- attempted the task,

- completed the task.

And there may be a deeper resistance in the breaking down of words. A two syllable word, such as ‘sunshine’ represents a concept, vital for life, that is associated with similarly important one syllable words, such as ‘light’ and ‘sun’. For some children, who are more literal in their approach, segmenting a word may, for them, symbolise breaking down their experiential knowledge.

Although many children may enjoy pulling words apart and rebuilding them, there are some who may feel that a word cannot be segmented without being permanently ‘damaged’. For these children, the playfulness of segmenting and blending needs greater emphasis.

But fundamentally, this is not a trivial matter. If a child cannot read, they will not be able to access the curriculum and will be seriously disadvantaged. Phonemic awareness needs to be explicitly taught until it becomes automatic. So, here’s how to unlock blocked phonemic skills, that are vital for the development of blending and segmenting.Blending and Segmenting Game

This is a technique that has worked with mainstream children aged from five to seven years, as well as with older children in special schools, who are not progressing with phonics.

Blending and Segmenting Game

First start with blending:

- think of a two-syllable word that will appeal to the child, such as ‘football’.

- point to the ceiling using your left index finger (level with the child’s face) and say ‘foot’

- point to the ceiling using your right index finger (level with the child’s face) and say, ‘ball’

- bring the two index fingers side by side and say, ‘football’

- ask the child to copy and then join in with you - exaggerate the syllables with a playful voice.

- practise with other words until the child can do this independently.

Now segmenting

- bring your two index fingers side by side, exactly as before and say, ‘foot…ball’,

- make the right index finger ‘disappear’ into the right fist and say “Take away ball”

- flex the left index finger a little and say, “What’s left?”

- if they followed the game, they will say, “Foot”.

- if they are confused, say, “Let me show you again…” and repeat the process exactly

- once this technique has been understood, explore taking ‘foot’ away.

This ‘game’ helps children to:

- understand that breaking and building sounds is playful and that words are malleable.

- regard word games as similar to counting games - their fingers can help them.

- develop an effective visual aid which allows greater stability in a weak working memory.

- self-regulate any associated subconscious emotional responses, when breaking down words.

Would you like to have a list of two syllable words to use while playing this game?

Click here to receive a pdf of the Blending and Segmenting Game and a Wordlist.

Did you enjoy this post?

Continue reading about the fascinating world of phonological processing.

When rhythm and phonics collide - discover the confusable features of certain phonemes and why rhythm brings clarity to this issue.

When rhythm and phonics collide part 2 - explore rhythmic and prosodic differences between consonant and vowel sounds

Conversations, rhythmic awareness and the attainment gap - a rhythm-based perspective on the influential Hart & Risley study of the ‘word gap’ between affluent and disadvantaged families.

Rhythm and probability underpin implicit language learning - this is about information processing in the first eight months of an infant’s life.

Back to school and reading at home: How to set good reading habits for the new school year

7 September 2023

Early reading was hit hard by the pandemic and in this coming academic year we’ll see a real focus on narrowing an attainment gap between stronger and weaker early readers. Although children are taught the phonics skills that they need to read well in school every single day, reading at home with an adult builds the foundations for strong progress. Every child needs to make strong progress to read well, to develop their confidence as well as their enjoyment in reading. Read on to start the new term with good reading habits and get a FREE downloadable Good Reading Habits Checklist.

What are good reading habits?

Good reading habits develop at home every time a child:

- Opens their book bag and practises reading aloud

- Talks about what they have read

- Re-reads the books that match the phonics lessons at school

- Practises grapheme-phoneme correspondence.

Good reading habits are easier to maintain, more rewarding and productive when:

- Reading at home happens at the same time every day

- The same parent guides and supports the child

- Repetition and re-reading is encouraged, as this helps the child to develop resilience, a growth mindset and perseverance.

Choosing the same time of day, every day, creates a strong and consistent reading habit.

The best times to open up the book bag are either straight after school with a drink and a snack or, first thing in the morning before getting ready for school (set the alarm clock!).

How many minutes of reading are enough?

Reading at home is a bit like talking at home. It doesn’t need to be measured by time. Reading sessions can be spent talking about the pictures, the characters and the words in the book. By simply helping the child to enjoy reading, the time will fly by.

A child might need reassurance and plenty of encouragement to stay engaged with the book and to practise the words. And that’s absolutely fine! However, the main goal is to support the child’s reading skills. So spend at least ten minutes every day on reading and re-reading the words in the book.

- Reading for ten minutes every day makes a real difference and builds up over time.

- An early reading habit of twenty minutes every day has a powerful lifelong impact.

Parents who read at the same time every day with their child set them up for success at school.

Of course:

- It’s not always easy to stick to new habits.

- It takes devotion and determination to keep up the reading habit every single day.

- And at the beginning of the school year, it’s easy to knock a new reading routine off track.

What gets in the way of reading at home?

Anything new, noisy or shiny will distract a child from reading. Good reading habits are easier to maintain in a calm, quiet and gentle atmosphere.

Parents can avoid interruptions if they:

- Make sure that the child’s siblings have something interesting to do

- Check all mobile devices are muted.

One of the biggest challenges at the beginning of the new school year is supporting children’s reading AND preparing food for the family.

What’s the solution?

- Plan meals in advance - and this could also save money.

- Cook in batches at the weekends and freeze the portions to save time on school nights.

Inevitable disruptions to good reading habits come around every year shortly after the beginning of term.

For instance, there are:

- Invitations to birthday parties

- Halloween costumes to plan and make

- Firework displays to watch.

Is it okay to skip reading at home occasionally, when everyone is having fun?

No, it’s not okay because the effects of falling behind in reading impact the rest of the child’s schooling. And parents need to avoid making this very common mistake:

- It’s very easy to slip out of a good reading habit into a disorganised one.

- The pace of the early reading curriculum is very brisk and doesn’t ease up because of birthdays or other festivities!

- Children fall behind very quickly if they are note reading at home every day.

Is an early morning reading habit the answer?

There are clear advantages, as an early morning reading routine:

- Allows more space in the child’s day for after school activities, sports, and parties.

- Before school can be very calming for children.

- Encourages the child to arrive at school on time, with bags of confidence.

What are the three questions every parent can ask their child when they are looking at a new book?

It’s fun to ask these questions, as they will give the parent a sense of their child’s level of curiosity and connection with reading a particular book.

- What do you think this book is about?

- What can we see in this picture?

- What do you think happens in this book?

What are the best ways to overcome challenges when reading at home?

A playful attitude, with parent and child ‘learning together’ helps the child to develop problem-solving skills and strategies, such as:

- “Ooh, I wonder what this word sounds like?”

- “Do we know the first sound of this word?”

- “Let’s listen to what happens if we say it slowly together.”

Sometimes, a phonics-based approach, which focuses on the sounds of words is something of a barrier for parents, particularly if they themselves had struggled to learn to read. I’ve seen very successful workshops in schools called ‘Family Phonics’. These workshops not only break down parents’ fears around phonemes, but also help parents and teachers to build wonderful collaborations for the benefit of the children. And everyone wins because we want all our children to become confident fluent readers!

What is a reading diary for?

Many teachers and parents use a reading record or a reading diary. This records the number of times the child reads to the parent and the teacher. It’s a vital tool as it proves that at home and at school there is enough input to keep the children’s reading development on track. Remember to put a pen or a pencil in the book bag to make it easier to make updates every day.

Are rewards for reading a good idea?

Many parents and teachers use star charts or stickers to encourage desired behaviour from children. However, reward systems are more powerful when they are reserved for unexpectedly good behaviour. Reading is a necessary life-skill. It’s like brushing your teeth. It should be part of the daily routine.

The closeness between the parent and child whilst reading at home IS an important factor. But there are also many invisible rewards of good reading habits that last a lifetime:

- Stronger communication and language skills

- Development of critical thinking skills

- Improved focus

- Improved memory

- Development of empathy

- Growth of vocabulary

- Development of reading comprehension skills

- Development of connections between different books, stories and ideas

- A love of reading for pleasure and an appreciation of authors’ writing skills.

If you enjoyed this post, click here to receive the Good Reading Habits Checklist. it’s FREE!

You may also enjoy these posts on related topics, such as:

Narrowing the gap through early reading intervention

Releasing resistance to reading

Musical notation, a full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection

10 January 2023Many years ago, I was asked to teach a group of children, nine and ten years of age to play the cello. To begin with, I taught them to play well known songs by ear until they had developed a solid technique. They had free school meals, which in those days entitled them access to free group music lessons and musical instruments. One day, I announced that we were going to learn to read musical notation. The colour drained from their faces. They were agitated, anxious and horrified by this idea.

No! they protested. It’s too hard.

After all these lessons, do you really think I would allow you to struggle? I asked them.

The following week, I introduced the group to very simple notation and developed a system that would allow them to retain the name of each note with ease, promoting reading fluency right from the start. This system is now an integral part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. It was first developed for these children, who according to their class teacher, were unable either to focus their attention or to learn along with the rest of the class.

After only five minutes, the children were delighted to discover that reading musical notation was not so difficult after all.

I can do it! shrieked the most excitable child again and again, and there was a wonderful atmosphere of triumph in the room that day.

After six months, the entire group had developed a repertoire of pieces that they could play together as a group and as individuals. It was at this point that Ofsted inspected the school. The Headteacher invited the children to play in full school assembly in the presence of the Ofsted inspection team. They played both as a group and as soloists. Each child announced the title and composer of their chosen piece, played impeccably, took applause by bowing, and then walked with their instrument to the side of the hall. At the end of the assembly the children (who were now working at age expectation in the classroom) were invited to join the school orchestra and sit alongside their more privileged peers. The Ofsted team placed the school in the top category, ‘Outstanding’.

If you would like to learn more about this reading programme, contact me here.