The Rhythm for Reading blog

All posts tagged 'rhythm'

Improving reading comprehension and awareness of punctuation

29 November 2023

If curriculum lies at the heart of education, it is reading comprehension that enables the vibrant health and vitality of learning. If the curriculum is narrow, the heart of education is constricted, pressured and strained. Without the breadth and rigour of a curriculum that encourages expression and criticality, there may be too little in terms of intrinsic motivation to inspire effective reading comprehension.

Growth mindset, resilience and perseverance cannot compensate for a narrow and impoverished curriculum, nor can they motivate children to want to engage with learning. However, a rich and rewarding curriculum can encourage children’s natural curiosity, drive and self-sustaining motivation, which can bring focus, enjoyment and depth of engagement to reading comprehension.

If a child cannot read, they will not be able to access the curriculum and this has far-reaching consequences not only for the individual, but for all of us as well. A generation of motivated and enabled children who access and enjoy everything that their education has to offer without the limitations of fragile reading, will adapt and adjust with greater confidence to whatever the future holds.

Reading comprehension offers everyone enriched opportunities to develop their aspirations, talents and interests. Indeed, it is through reading comprehension that pupils become lifelong learners and gravitate towards the topics that most interest them. As a starting point, children must engage with different types of reading - fiction, non-fiction and poetry, and discover the many different styles of writing. Engaging with a wide range of reading material empowers children to take their first steps on their future path and to expand their vocabulary. Up to ninety per cent of this is encountered in books rather than day-to-day speech.

Some reading experts have said that a lack of requisite vocabulary or background knowledge can limit a child’s ability to access a text. This mismatch between the text and the child’s prior experiences does not happen in a vacuum and need not limit a child’s education. Lacking the vocabulary or the knowledge to access a passage of text, a child must be encouraged to fill in the gaps at school.

Outstanding schools that have a large proportion of pupils with English as an additional language (EAL), address this issue of a limited vocabulary by immersing the children in ‘enriched’ environments. Different topics that do not come up in day-to-day conversation such as space exploration, deep sea diving and mountaineering, are exciting for children and these schools use corridor spaces as places where children can sit in a ‘spaceship’ or a ‘submarine’ or a ‘safari jeep’ and listen to information about the topic, use word banks, hold relevant books and enjoy the illustrations.

What is reading comprehension?

Reading comprehension is not only an understanding of the text - this could be gained from the relatively static process of looking at illustrations or chapter headings. It is a more dynamic process that integrates information as the text is read. This happens when we hear spoken language: we follow along and reciprocate in real time. Reading comprehension is like a conversation, in the sense that it is a social invitation to extract meaning from what is written. If it does not engage the child socially, the text is unlikely to be understood.

What is the most important key to good comprehension?

When we are reading, the most important key to good comprehension in my view is the social connection with the words. Children make this connection at home before they start school, having been read to by parents or siblings or other caregivers since infancy. These adults will have built social cues such as tone of voice and rhythm into their child’s earliest experiences of books. These children also arrive at school with other social assets such as a strong vocabulary and a positive attitude towards reading.

Conversely, children with a more limited vocabulary may need to build their social connection with reading from scratch and they may also feel anxious about learning for any number of reasons. For them, the usual cues of social engagement such as tone of voice and rhythm are missing from the ‘marks on the page’. So a child with a limited vocabulary and little experience of being read to needs to discover for themselves that reading is primarily a social act before their reading comprehension can develop traction.

What is punctuation?

Young children learn through play. This involves a sense of heightened arousal as well as social engagement. Even a child playing on their own will be vocalising a narrative of some kind, involving specific sounds and patterns. Punctuation offers an opportunity to engage with a child’s instinct for social engagement and meaning-making through play. Exaggerated voices, list-building, sudden sounds, humour and suspense are invitations to play with words. In the Rhythm for Reading programme we occasionally use a word, purely for fun, at a rhythmically important moment in the music. One such word is, ‘Splash!’ This word marks the end of a very up-beat tune about dolphins and the children love to celebrate this final moment with pure joy. Their social engagement and their playfulness are central to the entire programme, so reading becomes an act of social meaning-making, regardless of the development of their vocabulary.

At the beginning of a child’s literacy adventures at school, conventions of using punctuation are taught in the context of meaning-making and involve the correct use of capital letters, full stops, question marks, commas, exclamation marks, two types of apostrophes and speech marks.

Then other punctuation marks are introduced, such as colons, semi-colons and brackets as a way to enhance meaning-making. Finally, the other conventions involving quotation marks, dashes and hyphens can be added as the child embarks on writing that involves more informality, unusual language, citations and compound words.

Moving beyond conventions and back to social engagement, it is important to consider the ‘state’ of the child. An anxious child with a limited vocabulary will be overloaded emotionally and grapple with word-by-word processing. Their working memory may not have sufficient resources to manage punctuation. A withdrawn child, on the other hand, may have insufficient motivation to engage with reading or writing. By addressing their ‘state’ through a rhythm-based approach, these social-emotional learning blocks can, and do, shift.

Why is punctuation important in reading comprehension?

Punctuation is a shorthand that guides the reader to recognise familiar types of meaning-making. A series of commas tells the reader that they are going to make a meaningful list. A question mark and an exclamation mark invite the reader to ‘play’ with the concept of ‘an unknown’ or ‘novelty’ respectively. Both are motivational to the child’s instinct for social engagement - their natural curiosity. The full stop is an important rhythmic cue that defines grammatical structures that can stand alone. In a conversation, this could be an opportunity for facial expression or a nod of the head which acknowledges the social dimension of meaning making. In terms of reading aloud, the reader’s prosody - the rise and fall of their voice, shows that the information unit has completed a rhythmic cycle.

In a conversation, the rise and fall of the voice, as well as the dimensions of rhythmic flow create the socially engaged cues of meaning-making and also support reading fluency. These cues are exaggerated by parents when they talk to their young children. Defining utterances in this way creates a structural blueprint for language and social engagement that we as social beings use when we interact. Similarly, conventions of punctuation correspond to these same structures that infants learn in the first eight months of life, as they acquire their home language. For this reason, children intuitively understand punctuation marks when they read with fluency, provided they are socially receptive to and engaged by the content of they are reading.

Why do children struggle with punctuation?

Punctuation is the dynamic part of reading that organises individual words into grammatical chunks and ultimately, meaningful messages. It functions as a counterpart to grammatical awareness because punctuation as a symbolic system is processed ‘top down’ from the conscious to subconscious, whereas grammatical awareness, which was established in infancy is processed bottom-up, from subconscious to conscious. It’s important to recognise that conscious processing is relatively slow, whereas subconscious processing usually occurs at lightning speed. Children who struggle with reading, and have not integrated these different processing speeds, experience reading as a kind of rhythmic block, often referred to as a ‘bottleneck’. Although many academics have described this as a problem with processing print, in my experience this ‘bottleneck’ is more related to a child’s subconscious levels of social engagement as well as their ‘state’ in terms of their perceptions, attitudes, emotions and level of confidence.

The Rhythm for Reading programme addresses the so-called ‘bottleneck’. Changing a child’s ‘state’ involves ‘neuroplasticity’ or ‘rewiring’ unhelpful ‘habits of mind’ and it is possible to achieve this through regular, short-bursts of learning using high intensity, repetitive and rhythmical actions.

To find out more about how the Rhythm for Reading programme changes a child’s ‘state’, click here to read our Case Studies and click the red Sign Up button at the top of this page to receive weekly ‘Insights’ and news about our new online programme.

If you enjoyed this post about reading comprehension and punctuation, keep reading!

Rhythm, punctuation and meaning

The comma, according to Lynn Truss, clarifies the grammatical structure of a sentence and points to literary qualities such as rhythm, pitch, direction, tone and pace.

Stepping up: from phonemes to comprehension

The sentence as a whole and coherent unit is vibrant, elastic and flexible with its meaning perceived not through the synthesis of its many phonemes, but through its overall rhythm and structure.

Discover the heartbeat of reading

Just as a heartbeat is organic, supporting life in each part of the body from the smallest cells to the largest organs, rhythm in reading reaches systemically into every part of language. Like a heartbeat it spreads both upwards, supporting the structure of phrases and sentences and also downwards, energising and sharpening the edges of syllables and phonemes. Rhythm therefore brings the different grain sizes of language into alignment with each other.

What can we do to support the development of reading fluency?

22 November 2023

All children from all backgrounds need to learn to read fluently so that they can enjoy learning and fully embrace the curriculum offered by their school. A key challenge for schools is identifying an appropriate intervention that effectively supports reading fluency - a necessary part of a coherently planned, ambitious and inclusive curriculum that should meet the needs of all children.

The children who lag behind their classmates in terms of fluency are not a homogenous group. Although time-consuming and costly, one-on-one teaching is essential for those who struggle the most. However, short, intensive bursts of rhythm-based activity (Long, 2014) have been found to give a significant boost in reading fluency in the context of a small group intervention. This approach is an efficient use of resources as it supports those children who struggle with fluency in ten weekly sessions of only ten minutes.

An evidence-based, rigorous approach to the teaching and assessment of reading fluency leads to increases in children’s confidence and enjoyment in reading. Whilst logic might suggest that the difficulty level of the reading material is a barrier to the development of reading fluency, manipulating the difficulty level of the text does not directly address the underlying issue.

Reading fluency involves not only letter to sound correspondence, but also social reciprocity through the medium of print and therefore the orchestration of several brain networks. The social mechanisms of a child’s reading become audible when the expressive and prosodic qualities in their voice start to appear. This is why a more holistic child-centred perspective is helpful - it allows children to experience learning to read as a playful, rather than a pressured experience.

The pressure felt by children with poor reading fluency arises because of inattention and distractibility, as well as variability in their alertness, which pull them off-task. Compared with their classmates, these children are either more reactive and volatile in social situations, or quieter, and more withdrawn. Our rhythm-based approach uses small group teaching to reset these behaviours, by supporting these children into a more regulated state. Working with the children in this way helps them to adapt to the activities, to adjust their state and to regulate their attention within a highly structured social situation.

What are the key components of reading fluency?

Different frameworks describe fluency in different ways. From a rhythm-based perspective, the components of expression, flow and understanding are the most important. There is one more to consider - social engagement with the author - the person who wrote the printed words. The extent to which the child reads with expression, flow and understanding reflects the degree of social engagement while reading. One of the ways to accomplish this is to free the volume and range of the voice by encouraging a deeper involvement with the text. It’s easy to achieve this in books that invite readers to exaggerate the enunciation of expressive or onomatopoeic words.

Flow in reading fluency

The flowing quality of fluent reading shows that the child has aligned the words on the page with the underlying grammatical structure of the sentences. This sounds more complicated than it actually is and doesn’t need to be taught, because children activate these structures in the first eight months of life, when they acquire their home language. Accessing these deep structures during reading enables them to feel the natural rhythm in the ebb and flow of the language. However, there are many different styles of both spoken and printed language, as each one may have a different rhythmic feel. Feeling the rhythmic qualities of printed language is inherently rewarding and motivating for both children and adults: it allows the mind to drop into a deeper level of engagement and achieve an optimal and self-sustaining flow state.

Understanding in reading fluency

There is one prerequisite! Understanding printed language requires motivation to engage. Let’s call this the ‘why’. It involves a degree of familiarity with the context and a basic knowledge of vocabulary, which are both necessary to stimulate the involvement of long term memory, as well as a desire to become involved in the narrative. Many books introduce us to new concepts, vocabulary and contexts, but the ‘why’ must act as a bridge between what is already known and the, as yet, unknown. This ‘why’ compels us to read on.

About the ‘Why’

In a conversation there is a natural alignment between expression, flow and understanding. The energy in the speaker’s voice may signal a wide range of expressive qualities and emotions which help the listener to understand the ‘why’ behind the narrative, as well as keeping them engaged and encouraging reciprocation. The ‘why’ in the narrative is arguably the most important element in communication as it conveys a person’s attitude and intention in sharing important information about challenges or changes in everyday life and the experiences of individual characters - the staple features of many storylines or plots.

‘Handa’s Surprise’ by Eileen Browne

So, in Eileen Browne’s beautiful telling of ‘Handa’s Surprise,’ a humorous book about a child’s journey to her best friend’s village, the reader learns about the names of the fruits in her basket, the animals that she encounters and becomes curious to learn what happens to Handa as she walks alone in southwestern Kenya.

It isn’t necessary for young children to know the names of the fruits, such as ‘guava’, ‘tangerine’ or ‘passion fruit’. Despite the irregularities of words such as ‘fruit’ and ‘guava’ (and the need to segment ‘tangerine’ with care to avoid ‘tang’) children understand the story, having been introduced to the new (unknown) vocabulary in the (known) context of ‘fruit’. The child’s long term memory offers up the background knowledge of ‘fruit’ as a broad category, but adds the names of the new fruits under the categories: ’food-related’ and ‘fruit’ for use in future situations in their own life.

The new vocabulary in the story enriches children’s knowledge of fruit, but the ‘why’ of this tale is the bigger question… Will Handa complete her journey safely? Empathy for, and identification with Handa elicits, (subconsciously), an increase in the reader’s curiosity and brings further focus to the mechanisms of reading fluency. Once each new word has been assimilated into the category of ‘fruit’, reading fluency is self-sustaining and driven by plot development and empathy for the main character. Having read this story (and many others) with children, I have become aware that reading fluency must become closely aligned with the rule-based patterns of grammar, as these enable irregular words such as ‘fruit’ and ‘guava’ to be quickly assimilated into the flow of the story.

‘Jabberwocky’ by Lewis Carroll

A more famous and exaggerated example of this effect is Lewis Carroll’s ‘Jabberwocky’. Many of the novel ‘words’ invented by Carroll for this poem must be assimilated into the reader’s vocabulary. The process is much the same for made up, as it is for unfamiliar words. Long term memory offers up categories of animals and their behaviour, relative to the evocative sounds of ‘words’ such as, ‘slithy’, ‘frumious’ and ‘frabjous’.

The grammatical structure of each line of verse is kept relatively simple, allowing the narrative to feel highly predictable, as it is clearly supported by the regular metre. The repetitive feel of the ABAB rhyme structure guides the reader to use the conventions of grammar in anticipating, and thus engaging with the unfolding, yet somewhat opaque narrative.

Together, the features of repetition, rhythm and predictability strengthen coherence, so that the words are chunked together in patterns based on the statistically learned probabilities of spoken language. Deeper grammatical structures that sit beneath these rhythmic patterns are logic-based: they offer up meaning and interpretation based on micro-cues of nuanced emphasis, intensity and duration within the fluent stream of language, whether spoken or read.

Why is reading fluency important?

Reading fluency is important for three reasons and these also act as drivers of motivation and learning.

- Reading fluency brings the rhythmic patterns of language into alignment with deeper grammatical structures that are necessary for meaning-making.

- These structures - which are probabilistic - bring into awareness the most likely next words, phrases, and developments in the story. These are not based on pure guesswork, but reflect the reader’s understanding of the genre, the context and text-specific cues.These include appraising the shape of the word, and automaticity in recognising the shapes of letters (graphemes), words and their corresponding sounds (phonemes). These cues are necessary, but not sufficient to orchestrate fluent reading.

- Reading fluency supports children as they expand their vocabulary.

The majority of studies show that:

- A strong relationship exists between vocabulary size and social background,

- Up to ninety per cent of vocabulary is not encountered in everyday speech, but in reading,

- Vocabulary is particularly important for text comprehension,

- Children’s books tend to include more unfamiliar words than are found in day-to-day speech.

The first two mechanisms work together symbiotically to anticipate, adapt and adjust to what is coming up next in printed language, similar to when we hear someone speaking. The third mechanism changes a child’s perspective on life. Teachers and parents need to expose children to printed language, including the unfamiliar and orthographically irregular words, simply because it is through reading fluency that these words are assimilated into a child’s lexicon.

How do you measure reading fluency?

Listening is key to measuring reading fluency. If a child practises a sentence by repeating it at least three times, there should be a natural shift in the level of engagement. In a child struggling with reading fluency, four attempts may be necessary. Here is an example of the process of refinement through repetition.

- A beard hoped up to my wind….ow.

- A b….ir…d h…o….p…p….ed up to my w…in, win…..d…..ow.

- A b…ear…ir…d, b..ird, BIRD…. hopped up to my wind…ow (long pause) window.

- A bird hopped up to my window.

The pivotal moment was when ‘b-ird’ became BIRD. This would have sounded louder because the child’s voice would have become clearer once the (known) category ‘bird’ was activated in their long term memory and the meaning behind the word was understood. Long term memory offered up the strong likelihood of ‘hopped’ in relation to the category ‘bird’ and this helped the child to extrapolate that the final word must be a ‘thing’ to hop towards. This was not guesswork, nor was it an exclusive reliance upon phoneme-grapheme correspondence, but an alignment of 1. long term memory (including probabilistic language processing) with 2. visual recognition of letters and knowledge of the sounds they represent (including a degree of automaticity).

Reading fluency can be measured in terms of engagement, expression, flow and understanding and in the Rhythm for Reading programme we specialise in transforming children’s reading at this deep (subconscious) level. Children move from relying on unreliable decoding strategies (because the English language doesn’t follow the regularities of letter to sound correspondence), through to full alignment with the language structures that underpin their everyday speech. Once this shift has taken place, the children are able to enjoy interacting with books and they also grow in confidence in other areas of learning and social development.

We have helped many hundreds of children to engage with reading in this natural and fluent way using our rhythm-based approach, which is delivered in only ten weekly sessions of ten minutes. There are almost a thousand case studies confirming the relationship between our programme and transformations in reading fluency. Click the link to read about selected case studies.

If you have enjoyed reading this post, why not sign up for free weekly ‘Insights’. You will be among the first to know about special offers and our new online programmes!

If reading fluency is of interest, you may enjoy these posts

Reading fluency: Reading, fast or slow?

Schools ensure that all children become confident fluent readers, so that every child can access a broad and balanced curriculum. Fluent reading underpins a love of reading and is an important skill for future learning and employment and it also enables children to apply their knowledge and skills with ease.

Reading fluency again - looking at prosody

Prosody is closely associated with skilled reading, being integral to fluency and a predictor of achievement in reading accuracy and comprehension. Prosody is not taught, but it is a naturally occurring feature of competent reading. The words on the page may be arranged in horizontal lines, but a good reader transcends the visual appearance of the words, allowing them to take on a natural, flexible and speech-like quality.

Many teachers and head teachers have remarked on the improvement in their pupils’ reading fluency, so it seemed important to try to capture what has been happening. Of course, there are different ways to define and to measure reading fluency, but here is a snapshot of what we found when using two types of assessment.

References

Eileen Browne (1995) Handa’s Surprise, Walker Books and Subsidiaries.

Long, Marion. “‘I can read further and there’s more meaning while I read’: An exploratory study investigating the impact of a rhythm-based music intervention on children’s reading.” Research Studies in Music Education 36.1 (2014): 107-124.

Skulls and Magic: Ancestors, Trances, Dancing and Tea

25 October 2023

Did you know that ninety per cent of our vocabulary is encountered in reading and not in everyday speech? Books can introduce us to some spectacular ideas and gruesome knowledge at Halloween. Folk tales and myths in particular can induct us to knowledge about our world and rituals that date back many thousands of years. Although the origins of Halloween are attributed to the Celtic tradition, many of its themes as we know them today have rich and ancient origins. dating back to the beginnings of the Neolithic period. Humans have preserved, decorated and celebrated their ancestors’ skulls for thousands of years.

Here, I review two new Halloween books ‘Where’s my Boo!?’ by Nicholas Daniel, and ‘The Skull’ by Jan Klassen. “Where’s My Boo!?” is superficially an adorable story that actually deals with fear - the type of fear that steals your voice, that leaves a person feeling frozen and silenced. A ghost goes on a quest to ‘reclaim’ its ‘Boo!’ and even borrows the voices of others. This book delights in three ways. First, it uses a predictable pattern of rhyming couplets that is consistent and make it fun to guess the final word. Also, there’s a persuasive feeling of buoyancy in the illustrations and a font that pretty much mirrors the lilting feel of the language. Lastly, a huge sense of relief is palpable when the ghost stops searching and listens to the voice within. The encouraging message of this book is that our ‘true Boo!’ is the one that everyone loves and needs to hear.

‘The Skull’ is a retelling of a Tyrolean folktale. It’s a fascinating blend of folklore and symbols, reworked through a contemporary lens. Skulls have been polished and cherished for millennia, and in Halloween season, surrounded as we are by skeletons and carved pumpkins, I was curious to dive deeply into the underpinnings of this story.

The original version of this folk tale is deeply symbolic. The most mysterious and magical elements of the story, to my mind, have been ‘cleansed’ during Klassen’s retelling. However, the relationship between the main character, ‘Otilla’ and the ‘Skull’ remains the same across three different versions - and I’ll unpack a few points for the sake of comparison. The character of ‘The Skull’ is best described as a cherished ancestor, perhaps as a once precious elder of the community. There’s evidence that ten thousand years ago, people polished and decorated skulls, perhaps as a token of respect for deceased loved ones, or as a way to maintain a ‘connection’ with them. In each version of the story there is also a ‘Skeleton’ character, which wants possession of the ‘Skull’. The child ‘Otilla’ confronts the ‘Skeleton’ in the climax of the story and after this point, each reworking retells the folk tale in a different way.

In the original, according to Klassen, once the curse of the ‘Skeleton’ has been broken, it vanishes. At that moment, the ‘Skull’ turns into a beautiful lady dressed in white and the castle is filled with children and lovely things to play with. This lady gives everything in the castle to ‘Otilla’ before disappearing into the sky.

Another earlier version, written by Busk and edited by Rachel Harriette dates from the nineteenth century, entitled, “Otilia and the Death’s Head’ or, ‘Put your trust in providence’. It was published in London in 1871 and resonated strongly with the opening section of the well known tale ‘Cinderella’, as the young Otilla was both orphaned and resentful of her stepmother.

Overwhelmed by grief and her own vulnerability, Otilla runs away from home into the Tyrolean forest, all the while hearing her deceased father’s voice guiding her and urging her to trust in God. Hungry, cold and close to death herself, she discovers a castle and is welcomed by a speaking ‘Death Head’.

She undertakes specific tasks for the ‘Death Head’. She cooks in the kitchen, sleeps in a strange bedroom and faces her fear of the ‘Skelton’ that rattles its bones at her. However, guided by her father and trusting in God, she is resolute and fearless. The next morning, the ‘Skeleton’ is transformed into a beautiful lady dressed in white, who, having shown a lack of appreciation for all the wonderful things that life had given her, had been trapped in the castle. She turns into a dove before flying away.

Otilla displayed no fear when confronted by the ‘Skeleton’ and had broken the spell through the strength of her faith. Having inherited the castle from the lady in white, she invites her stepmother to enjoy it with her, and domestic peace and harmony are restored.

In a wonderful book called, ‘Decoding Fairytales’ by Chris Knight, Professor of Anthropology at UCL, the reader is guided through a system of symbols and signs based on the division of lived experiences as either ‘Other World’ (the world of trance, near death experiences, ceremonial masks and rebellion) or ‘This World’ (the orderly world of compliance, harmonious living and surrender). ‘Halloween’ of course is a celebration of the ‘Other World’.

To appreciate the contrast between each ‘world’ we need to think about life before the internet, telecommunications, and even the use of electricity, when moonlight was the most important source of light after sunset. The phase of the moon was believed to control not only the tides and peoples’ physical safety, but also to influence their emotions.

In this list I’ve summarised Knight’s observations of the two ‘Worlds’.

‘This World’ versus ‘Other World’

- Moon Waning versus Moon Waxing

- Midday Sun versus Eclipse

- Silence / calm versus Thunder

- Day versus Night

- Life versus Death

- Dry versus Wet

- Cooked versus Raw / Blood

- Feasting versus Hunger / Being eaten

- Emergence versus Seclusion

- Harmony versus Noise / Chaos

- Surrender versus Rebellion

- Available versus Taboo

- Human Identity versus Animal Mask

‘The Skull’ is not a story about ‘This World’. In all three versions of the tale, Otilla leaves the mundane world of her old life behind and journeys into the ‘Other World’ - the liminal world where she encounters the transition between life and death, enchantment and rebellion.

In many fairytales, a young girl finds herself lost in a forest or has been secluded in a forest (by someone in her matrilineal line). Although the forest was familiar to Otillla, as she lay in the wet snow crying, she confronted her fear of the dark, of danger and of being alone at night. Klassen allows the reader to decide whether or not it was the wind calling Otilla’s name, whereas Harriette and Busk were unequivocal that Otilla could hear her late father’s voice guiding her onwards through the darkness. The forest is both a psychological and physical barrier, carrying the risk of death and cutting her off from the safety of her domestic mundane life.

In the Harriette and Busk version of the story, Otilla is given tasks to perform. The first is to carry the ‘Death Head’. The second is to take it into the kitchen and to make a pancake. To do this she uses eggs - a universal symbol of rebirth. In Klassen’s version however, she eats a pear (carrying connotations of fertility) with ‘The Skull’, makes a fire for them both and they ‘drink tea’ (we must imagine the type of tea) by the fire. Both versions feature the fire, and in fairytales such as Hansel and Gretel or the Gingerbread Man, a kitchen fire, in a cottage in the middle of a forest traditionally cues an opportunity for children to be cooked alive.

In the Klassen version of the story, the ‘Skull’ shows Otilla a wall where ceremonial animal masks hang, explaining that they were not to be worn (i.e. taboo). However, they walk down the steps to the dungeon and look at the ‘bottomless pit’ (a familiar theme in many myths and legends, perhaps representing an ‘underworld’ or the subconscious mind). In the accompanying illustration Klassen depicts both characters wearing the animal masks, which signals that they have crossed the threshold into the ‘Other World,’ the space between life and death where it is appropriate to wear animal masks and where taboos may be broken without consequences.

Otilla has spent the first night drinking ‘tea’ and exploring the dungeon with the ‘Skull’ and now trusts sufficiently to be taken to the top of the turret. The turret, like the dungeon was traditionally a place of seclusion for girls in many fairytales. As they climb the steps from the dungeon to the balcony and move from darkness into light, we may assume that a new day, the second day of the adventure has dawned.

They remove their masks as they reach the daylight and emerge into fresh air, but then the ‘Skull’ immediately takes Otilla into the ballroom, where the sun streams in through the window. The adventure continues as they wear the ceremonial masks and dance until evening. Traditionally, wearing an animal mask simply meant acknowledging the ‘animal side’ of the self, (the side that was inhibited by social norms during domestic day-to-day life). Having danced the second day away with the ‘Skull’, Otilla makes another fire and they ‘drink tea’ in the evening. She looks into the fire, it becomes a source of inspiration and cerebral power while the ‘Skull’ tells her about the threat of the ‘Skeleton’. Otilla sleeps with the ‘Skull’ on the second night and falls into a ‘deep sleep’.

In the middle of the night, the ‘Skeleton’ appears just as predicted and tries to steal the ‘Skull’ from Otilla. The girl prevails and shows the ‘Skeleton’ that she is stronger and smarter in Klassen’s secular version (and spiritually disciplined and protected in the Harriette - Busk version).

According to Klassen, the ‘Skeleton’ chases the girl, who clutching the ‘Skull,’ leads it up to the top of the turret, throws it over the edge, and hears it shatter upon impact with the ground.

Later in the story, while the ‘Skull’ sleeps, Otilia cremates the ‘Skeleton’s’ fragmented bones. [According to Knight, fire is a traditional symbol of marriage and stands in opposition to blood, a traditional symbol of kinship.] In Klassen’s contemporary narrative, Otilla accepts an invitation to cohabit with the ‘Skull’, having made the ‘Skeleton’ disappear, and thus she emerges on day three of her adventure into a new domestic life.

In the original version and Busk’s retelling of it, the ‘Skeleton’ transforms into a beautiful lady at the end of the story, reminiscent of Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother. In both fables, the young girls have a strong affinity with the tempering and purifying power of fire, and both have lost their mothers. It would also seem that bereavement, extreme anxiety, fear and stress in a pubescent child, particularly after drinking a herbal brew such as tea, might induce such visions. But, in Klassen’s telling of the tale, these magical ‘other worldly’ elements have been removed. Instead, the ‘Skull’ offers Otilla companionship and a new home.

If the underlying elements of this story resonated, you might enjoy reading more about trance, rhyme, rhythm and language in these posts:

Rhythm, Flow, Reading Fluency and Comprehension: In extant societies, traditional life ways include hunting and gathering. For sheer survival, loud communal singing and drumming are also essential for deterring the big cats that may predate infants on the darkest of nights.

Rhythm, attention and rapid learning: Boredom and repetition generate trance-like states of attention, whereas novelty and a switch in stimulus create a rapid reset. Ultimately the attention span plays a role in predicting where and when the next reward or threat is likely to occur.

Practising poetry - The importance of rhythm for detecting grammatical structures: Rhythmical patterns in language cast beams of expectation, helping to guide and focus our attention, enabling us to anticipate and enjoy the likely flow of sound and colour in the atmosphere of the poem.

How we can support mental health challenges of school children?

11 October 2023

The waiting lists for local child and adolescent mental health services- ‘CAMHS’ are getting longer and longer. Teachers and parents are left fielding the mental health crisis, while the suffering of afflicted children and adolescents deepens with every day that passes. Young people’s mental health challenges cannot be left to fester, as they affect their identity, educational outcomes, parental income and resilience within the wider community. Here are 10 key strategies that parents and teachers can use to support children and adolescents dealing with distressing symptoms of mental health challenges while they are waiting for professional help.

1. A calm educational environment

The size of the school seems to determine the quality of the learning environment to some extent. If every class takes place in a tranquil atmosphere, this means that every teacher takes responsibility for the ambience in every lesson. In ‘creative’ subjects such as music, art and drama, it is particularly vital that children participate in lessons where respect both for learning and for every student is maintained. An ethos of respect for every student is easier to sustain in a calm atmosphere. Children with mental health challenges are more likely to cope for longer in this setting, where they are better able to self-regulate any difficult feelings that may arise.

2. A space to talk

In a school it is important that teachers and children have spaces where they are able to discuss and resolve pastoral or academic challenges in privacy, rather than for example, in the middle of a busy corridor. This is incredibly important for the more vulnerable pupils in our communities. Those with special educational needs and disabilities need to be supported with a particular focus in terms of social, emotional and mental health. A place where children are able to ask for help or advice from the pastoral team immediately shows all pupils that this is a caring school that values their feelings, responds to their questions and most importantly, takes their mental health challenges seriously.

3. Listening from the heart

The pressure of workload on teachers is enormous, and yet according to research, teachers are more effective in the classroom when they not only show their passion for the subject, but also that they care deeply about the children they are teaching. Both these factors unfortunately can lead to teacher burn-out, which would obviously diminish their capacity to listen from the heart.

Arlie Hoschild’s ’The Managed Heart,’ discusses ‘emotional work’ as an integral but undervalued and unrecognised aspect of many public-facing roles.

Teaching is clearly one these, requiring intense and constant emotional input. Sadly, many of the best and most dedicated teachers suffer because they are so invested in pupils’ learning and personal development.

It is vital that school leaders cultivate an environment that values the well-being of teachers, protects them from abuse, prevents them from burning out and avoids unnecessary workload. Teaching can be incredibly fulfilling, but often feels all-consuming. It is therefore vital that teachers have realistic and sustainable workloads. Our teachers deserve to have time to recharge during the school day so that they are better able to support pupils’ mental health challenges, particularly if they work as part of a pastoral team.

4. Compassionate reassurance

Much has been said about empathy in recent years, but compassionate reassurance achieves a stronger outcome in less time. Compassion involves complete acceptance of the situation, as well as the capacity to hold all the challenges of that situation in mind, which is why it is easier to help students to feel emotionally ‘safe’, as they are more likely to begin to self-regulate. This involves being able to breathe deeply and slowly, feel physically more relaxed and more connected to their body, which may enable them to be better able to express their feelings and to share their concerns more openly.

5. Offering quality time with no distractions

Imagine a nine year old child, overwhelmed by a challenging situation and dealing with a mental health challenge, such as acute anxiety. One day, they feel ready to trust a teacher, to open up and to disclose their concern, but to their disappointment, the teacher must rush away to deal with something rather ‘more urgent’.

Their rational response would say, ‘Yes, emergencies happen, but my feelings are not as important as an emergency.”

At the same time, their vulnerable feelings might achieve a ‘shut down’ in their central nervous system and a dread of abandonment or rejection could trigger an acute attack of panic or anxiety or other distressing feelings and thoughts.

It is important for the child that the teacher stays physically present with them until that conversation or connection has reached a mutually agreed end point. If not, a negative spiral can quickly gain momentum if the ‘end’ of the conversation or connection feels abrupt or unplanned.

6. Practising gentle kindness

In day to day life, if we practise gentle kindness, it is obvious that we are not interested in conversations that are unkind. By walking away, we are showing that unkind remarks are not taken seriously. Gentle kindness begins in the mind, replacing judgmental thoughts with compassionate ones. It is arguably far easier to prevent mental health challenges than to treat them. Gentle kindness is a strong starting point for effective prevention.

7. Honouring the feelings

We all have feelings. Most people are uncomfortable with accepting all their feelings because difficult emotions such as shame or guilt or a belief that they are ‘not enough’ are pushed under the rug and barely acknowledged in our society.

Children and young people make comparisons between themselves and an ‘ideal’ version that they have seen online or experienced through parental scripting.

Here are a few examples of parental scripts or expectations of their child:

- To get married and have children

- To support the same sports teams as their parents

- To attend a certain school or university

- To take on the family business or join a certain profession

- To live in a particular geographical area

Sometimes this form of scripting is very ambitious and the child is expected to achieve one or several of these:

- To qualify to represent their country in an elite sports team or even in the Olympics,

- To win a scholarship to a particular school or university

- To have top quality examination results

- To break records or ‘be the first’

- To become so special and so talented that they are recognised for their accomplishments.

If these expectations are not fulfilled, harsh self-judgments and self-criticisms are likely to follow.

All of these negative beliefs, thoughts and feelings may well become so toxic that they may have a detrimental effect on the individual.

Conversely, a child who has too little support or stimulus from their family may well feel neglected and frustrated by a lack of attention and display challenging and self-pitying behaviour.

It is important to protect children from creating idealised versions of themselves. Even conscientiousness, which is often encouraged at school and is intrinsically admirable rather than harmful, can develop into an unhealthy source of anxiety and low-self-worth in certain situations.

8. Expressing the emotions

To express anger, frustration or resentment appropriately is natural and necessary. An outlet for emotions can be through sport or dancing or even music and singing. Some writers claim that anger has fuelled their best work! The response to these emotions has been carefully honed by warrior disciplines where the balance of managing and harnessing energy is the product of many years of dedicated training - for example Samuri warriors who are taught not only combative skills but also flower arranging. Cultures all around the world have found different ways to manage and express emotion in a socially accepted way. All of these practices involve allowing the body to discharge the emotions, as this is healthy.

Insufficient access to the creative curriculum means that pupils are restricted in terms of self-expression, the development of executive function, personal development and critical thinking. One appropriate way to express emotion is to dance and move, or sing and play music, allowing the body to cast off all the explosive, the aggressive and fiery feelings. Another way is to write down how these emotions feel and to really vent this on the page. These forms of physical release are very cathartic, though this needs to be done in a place, ideally out in nature - or where others won’t be disturbed!

9. Sharing worries and concerns

Young people and their parents need to share their challenges, worries and concerns. If a young person’s mental health challenges start to spiral and the situation deteriorates suddenly, this needs a swift and orchestrated response from everyone with a duty of care. It is not enough just to prioritise the children’s development of topical concepts such as, ‘resilience’, ‘growth mindset’ and ‘perseverance’. Above all, young people should not be left feeling isolated and surrounded by adults who are uncertain about what they ought to do, when facing a child who feels seriously overwhelmed, depressed or anxious.

Charities run helplines, manned by volunteers, and they train their people to offer a compassionate listening service. No one needs to suffer in isolation while they wait for professional help. As well as pastoral teams and family liaison workers in schools, there are helpline volunteers who work for charities that exist outside school. Together we can make sure that we support the families coping with child and adolescent mental health challenges every day.

10. Helpline numbers

Family Lives: 0808 800 2222

The Samaritans: 116 123

Childline: 0800 1111

NSPCC: 0808 800 5000

In an emergency dial 999.

Did some of this post resonate with your own experience?

If so, you might be interested in the important role played by rhythm in the management of stress in these related blog posts:

Education for social justice - This post sets out the mission, values and impact of the Rhythm for Reading programme in terms of reading and learning behaviour.

Rhythm, breath and well-being - This post unpacks the relationship between rhythm, breath and well-being in the context of smaller and larger units of sound, comparing the different types of breath used in individual letter names versus phrases.

Releasing resistance to reading - Discover how self-sabotaging behaviour and resistance to reading can be addressed through a rhythm-based approach.

Rhythmic elements in reading: from fluency to flow - Discover the importance of rhythm in activities that involve flow states and the way that elements of rhythm underpin flow states in fluent reading.

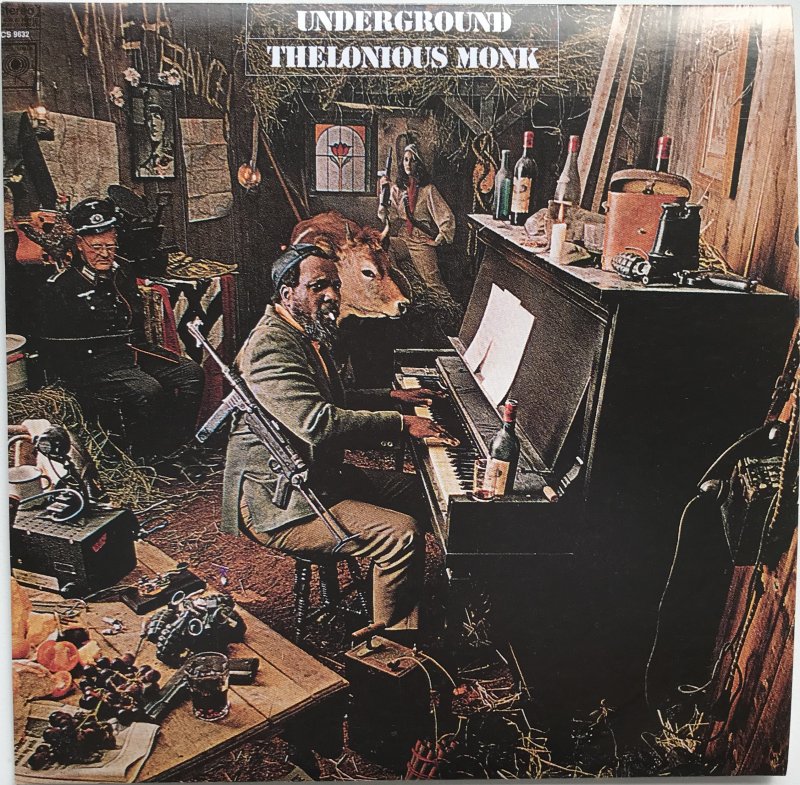

Thelonius Monk (1917-1982) A personal tribute

4 October 2023

Black History Month invites us to celebrate our differences more than ever. A knowledge-rich curriculum offers big ideas and invaluable depth of insight, but the creativity of Monk shows how knowledge can be developed to pioneer new forms and techniques. His music is unmatched in its capacity to inspire people of all ages because of its originality, which is preserved in the recordings. We are very fortunate indeed to be able to hear the playing and ideas of a musician who has led the development of an entire genre.

Having been hugely inspired by Thelonius Monk’s music, artistry and originality, I am going to express my appreciation for this exquisite musician here even though it’s impossible to do full justice to this musical icon through words alone. As a musician he is one of a kind - therefore this blog post will fall spectacularly short. But, as there is a huge gap between the struggles he endured during his lifetime and the huge amount of recognition that his artistry and humanity has received since his death, I’m going to highlight these contrasts here.

Back in the day…having graduated from the Royal Academy of Music in the late 1980s I was working with the superb musician, innovative pianist and inspirational composer, Roger Eno. I remember asking him about the artists he most deeply admired. Hearing Eno talking about Monk was so moving that I rushed out to buy a couple of albums - later that same day I listened closely to this giant of jazz.

A musician’s musician

Monk is truly a musicians’ musician. He inspires us to dig deeper and think bigger, to create with true integrity and honesty. There are forty-nine tribute albums made by admiring colleagues dating from 1958 right up to present times - the most recent was recorded in 2020. Posthumously, Monk has been awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1993), and the Pulitzer Prize (2006), but it wasn’t until 2009 that he was honoured by his home state in the North Carolina ‘Hall of Fame’.

My own first impressions, hearing this genius for the first time were a mixture of the deepest gratitude for his sincerity, and delighted astonishment in his freedom, playfulness and wit. There are other musicians who can match Monk’s dazzling piano technique - but what sets Monk apart for me, is that he took his mastery of the piano to a level of creativity that was utterly original.

Tenderness, wit and subversion

He used the piano to acknowledge tenderness, to dismantle and reweave others’ works and he delightfully subverted iconic works by other composers.Take for example, ‘Criss-Cross’ - in this track, Monk mocks Stravinsky’s ballet, ‘The Rite of Spring’ and we hear the saxophone and the piano calling out the famous opening motif played by the solo bassoon. Later Stravinsky’s ‘primal’ cross rhythms emerge through the composition, repurposed by Monk to restore percussive vibrancy to the nuanced rhythmic feel of these patterns.

Even more vivid perhaps, is ‘North of Sunset’. This track nods to the traditional blues which appear and disappear fleetingly, like shadowy outcasts in the glare of Monk’s quirky grammatical purity and the lean contours of his modern jazz style.

Architecture and musical form

Then there’s Monk’s relationship with depth and perspective. The best musical compositions of any genre have an architectural quality, with clearly defined form and proportions unfolding through sound. And yet in Monk we hear musical structures projected with the clarity of a hologram. For instance in the track, ‘Between the devil and the deep blue sea’ (based on Harold Arlen’s work of 1931) there’s infinite perfection in the proportions. Monk matches structural precision with a vivid portrayal of the title. At the end of his solo, he pushes the music over the edge and into vertiginous cascades of notes, shaking up our depth perception. Then there’s a curious restlessness that smoulders and smokes, depicting the title of the track perfectly.

Mimicry and magic

Other tracks that come to mind with a similarly dazzling precision are ‘Locomotive’ in which the breadth of the ‘groove’ evokes a driving mechanical feel, punctuated by crunchy chordal edginess. ‘Tea for Two’ is joyful in a suitably restrained and respectful way, but then unexpectedly explodes into a delightful sound world, mimicking the clatter of porcelain teacups and saucers. Elsewhere there are fleeting references to Schubert’s ‘Trout’ Quintet, with Monk conjuring witty and magical surprises.

Contemplative mood

It’s not all about wit and clever jokes. One of the things I most admire most about Monk as a performing artist is his use of space and silence. In ‘Japanese Folk Song’ the lyrical melody is stripped back to an emaciated dry skeleton, devoid of unnecessary or extra sounds and yet this transformation makes it all the more potent. Sharing with us the nakedness of the folk song, he displays his extraordinary gift for working with the essence of melody and the spaces between notes - in this case the chasms between chords, which achieve alchemy in real time.

In these tracks he shows his powers in dismantling a melody, a musical style, and a genre, then rebuilding it, but with the precision of a watchmaker whose fingers were immediately able to align the sound with whatever his mind envisioned.

Creativity flowing from ambiguous moments

After my own thoroughly classical training, encountering the exuberance of his playing reminded me what music was really for and how our creativity is the most authentic gift humans can offer to one other. For an illustration of this, in ‘We See,’ the abrupt musical fissures in the seemingly conventional introduction metamorphose into an extraordinary spaciousness. We soon discover that this ambiguity is the precursor, the necessary foundation from which a richer harmonic language emerges. Complementing the depth and complexity of the harmonies, we hear Monk’s ability to stretch and mould the elasticity of cross-rhythms and lilting flexibility of the phrases. Monk was always searching for the edges of extremes within the logic of balance, but in this track he appears to explore the boundaries of what’s possible in a more playful and yet still profound way.

Necessity as the mother of invention

When researching this post, I was sad to read about his struggles in life. He had even endured being beaten and unlawfully detained by the police. In every setback he displayed resilience and dignity. Surely the sophistication of his playing developed in part from sheer necessity: he had to create this unique style so that his music became his intellectual property - it was essentially impossible to copy. Listening to the melody in Monk’s ‘Bolivar Blues’ however, the ‘hit’ theme song ‘Cruella De Vil’ from Disney’s ‘1001 Dalmatians’ clearly shows more than a ‘homage’ to Monk. And he didn’t receive the full recognition that he deserved during his lifetime. Had Monk been awarded the Grammy and the Pulitzer while still alive, I would like to think that he’d have played more in the later years of his life and suffered fewer mental health issues.

Outcast or Genius?

Just as most books about reading development don’t mention rhythm, books about music tend not to mention Monk. But, Steven Pinker in ‘How the Mind Works’, is unequivocal under the heading ‘Eureka!’

And what about the genius? How can natural selection explain a Shakespeare, a Mozart, an Einstein, an Abdul-Jabbar? How would Jane Austen, Vincent van Gogh, or Thelonius Monk have earned their keep on the Pleistocene savannah?

Here’s part of Pinker’s brilliant answer to his own question:

But creative geniuses are distinguished not just by their extraordinary works, but by their extraordinary way of working; they are not supposed to think like you and me.

If you enjoyed reading about this giant of jazz, here are links to related posts about the value of music and creative subjects in the curriculum - (with a light touch of political opinion). As Brian Sutton-Smith once said,

The opposite of play is not work. The opposite of play is depression.

Creativity, constraints and accountability - Creativity is hardwired within all of us and there’s a playfulness in the ‘what if…’ process which guides an unfolding of impulse, logic and design.

The Power of Music – This post discusses Professor Sue Hallam’s ‘Power of Music’ - a document that reviews more than 600 scholarly publications on the effect of music on literacy, numeracy, personal and social skills to support the need for of music in the education of every child.

Knowledge, culture and control - Is history cyclical? As we move rapidly into climate crisis, artificial intelligence (AI) and a school curriculum dominated by STEM subjects, this post questions the present lack of emphasis on critical thinking and creativity.

Musical notation, a full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection

10 January 2023Many years ago, I was asked to teach a group of children, nine and ten years of age to play the cello. To begin with, I taught them to play well known songs by ear until they had developed a solid technique. They had free school meals, which in those days entitled them access to free group music lessons and musical instruments. One day, I announced that we were going to learn to read musical notation. The colour drained from their faces. They were agitated, anxious and horrified by this idea.

No! they protested. It’s too hard.

After all these lessons, do you really think I would allow you to struggle? I asked them.

The following week, I introduced the group to very simple notation and developed a system that would allow them to retain the name of each note with ease, promoting reading fluency right from the start. This system is now an integral part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. It was first developed for these children, who according to their class teacher, were unable either to focus their attention or to learn along with the rest of the class.

After only five minutes, the children were delighted to discover that reading musical notation was not so difficult after all.

I can do it! shrieked the most excitable child again and again, and there was a wonderful atmosphere of triumph in the room that day.

After six months, the entire group had developed a repertoire of pieces that they could play together as a group and as individuals. It was at this point that Ofsted inspected the school. The Headteacher invited the children to play in full school assembly in the presence of the Ofsted inspection team. They played both as a group and as soloists. Each child announced the title and composer of their chosen piece, played impeccably, took applause by bowing, and then walked with their instrument to the side of the hall. At the end of the assembly the children (who were now working at age expectation in the classroom) were invited to join the school orchestra and sit alongside their more privileged peers. The Ofsted team placed the school in the top category, ‘Outstanding’.

If you would like to learn more about this reading programme, contact me here.

Rhythm, phonemes, fluency and luggage

12 December 2022

Louis Vuitton began his career in logistics and packing, before moving on to design a system of beautiful trunks, cases and bags that utilised space efficiently and eased the flow of luggage during transit. He protected his designer luggage using a logo and geometric motifs. The dimensions of each piece differed in terms of shape and size, and yet it was undeniable that they all belonged together as a set - not only because they matched in appearance, but also because each piece of the set could be contained within a larger piece. In fact, the entire set was designed to fit into the largest piece of all.

The grammatical structures of language and music share this same principle that underpinned the Louis Vuitton concept. In a language utterance, the tone, the pace and the shape of the sound waves carry a message at every level - from the smallest phoneme to the trajectory of the entire sentence.

The shapes of individual syllables are contained within the shapes of words. The shapes of words are contained within the shapes of phrases and sentences. Although these are constantly changing in real time - like a kaleidoscope, the principle of hierarchy - a single unit that fits perfectly within another remains robust.

In music, the shapes of riffs, licks, motifs, melodies and phrases are highly varied, but the hierarchical principle remains a constant here too. The musical message is heard in the tone, the pace and the shape of the smallest and largest units of a musical phrase.

Just as Vuitton used design to create accurate dimensions at every level of his luggage set, the same degree of precision is also achieved at a subconscious level in spoken language and in music. A protruding syllable, the wrong emphasis or inflection can throw the meaning of an entire sentence out of alignment. A musical message is similarly diluted if a beat protrudes, is cut short or is lengthened, because the length and shape of an entire phrase is distorted.

Arguably, the precise dimensions in Vuitton’s groundbreaking designs reflect a preference for proportion and balance that also underpins human communication involving sound. Our delight in the consummation of symmetry, grammar and rhyme is present in the rhythm of language and also in music. At a conceptual level, it is ratio that unifies the Vuitton designs with language and music, and it is ratio that anchors our human experience in interaction with one another and our environment.

This concept of ratio, as well as hierarchical relationships and the precision of rhythm in real time underpin the Rhythm for Reading programme. Think of this reading intervention as an opportunity to reorganise reading behaviour using a beautiful luggage set, designed for phonemes, syllables, words and phrases. It’s an organisational system that facilitates the development of reading fluency, and also reading with ease, enjoyment and understanding.

Three factors to take into account when assessing reading comprehension.

28 November 2022

In the Rhythm for Reading Programme, progress in reading is measured using the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability 2nd edition revised (NARA II). Reading comprehension is one of three standardised measures in this reading assessment. There are many good assessments available, but I’ve stuck with this one because it offers three supportive features that I think are particularly helpful. If you are unfamiliar with NARA II, let me paint a picture for you. Detailed illustrations accompany each passage of text. For a child grappling with unfamiliar vocabulary or weak decoding, the illustrations offer a sense of context and I’ve seen many children’s eyes glance over to the illustration, when tackling a tricky word.

In practice, children come out of class one at a time for individual reading assessment. Each reading assessment lasts twenty minutes on average. The main advantage of an individual assessment over a group assessment is that the assessor is permitted to prompt the child if they get stuck on a word. In fact the assessor can read the tricky word after five seconds have elapsed, which helps the child to maintain a sense of the overall narrative. This level of support is limited by the rigour of the assessment. For example, an assessor would not give the definition of a word if a child asked what it meant and sixteen errors in word accuracy on a single passage of text signals the end of the assessment.

This particular individual format is more sensitive that all others in my opinion, because it minimises the influence of three cognitive factors on the scores.

Factor one: There is minimal cognitive loading of working memory as the child can refer back to the text when answering questions. In other words, they do not need to remember the passage of text, whilst answering the questions. This approach prevents a conflation between a test of comprehension and a test of working memory. Children may score higher on NARA II if working memory is likely to reach overload in other reading test formats, for example, if the child is required to retain the details of the text whilst answering comprehension questions.

Factor two: There is no writing involved in NARA II, so a child with a weak working memory achieves a higher score on the NARA II than on other formats if writing in sentences is a specific area of difficulty for them.

Factor three: The assessor keeps the child focussed on the text. This makes a big difference if a child is likely to ‘zone out’ frequently and to experience scattered or fragmented cognitive attention. In this instance, a child with weak executive function is more likely to achieve a higher score on the NARA II than on other formats, because of the support given to scattered or fragmented attention.

At the end of the ten weeks of our reading intervention, children have achieved higher scores not only in NARA II, but also in the New Group Reading Test and the Suffolk Reading Scales. Many children experience gains in cognitive control as well as reading fluency and comprehension.