The Rhythm for Reading blog

Skulls and Magic: Ancestors, Trances, Dancing and Tea

25 October 2023

Did you know that ninety per cent of our vocabulary is encountered in reading and not in everyday speech? Books can introduce us to some spectacular ideas and gruesome knowledge at Halloween. Folk tales and myths in particular can induct us to knowledge about our world and rituals that date back many thousands of years. Although the origins of Halloween are attributed to the Celtic tradition, many of its themes as we know them today have rich and ancient origins. dating back to the beginnings of the Neolithic period. Humans have preserved, decorated and celebrated their ancestors’ skulls for thousands of years.

Here, I review two new Halloween books ‘Where’s my Boo!?’ by Nicholas Daniel, and ‘The Skull’ by Jan Klassen. “Where’s My Boo!?” is superficially an adorable story that actually deals with fear - the type of fear that steals your voice, that leaves a person feeling frozen and silenced. A ghost goes on a quest to ‘reclaim’ its ‘Boo!’ and even borrows the voices of others. This book delights in three ways. First, it uses a predictable pattern of rhyming couplets that is consistent and make it fun to guess the final word. Also, there’s a persuasive feeling of buoyancy in the illustrations and a font that pretty much mirrors the lilting feel of the language. Lastly, a huge sense of relief is palpable when the ghost stops searching and listens to the voice within. The encouraging message of this book is that our ‘true Boo!’ is the one that everyone loves and needs to hear.

‘The Skull’ is a retelling of a Tyrolean folktale. It’s a fascinating blend of folklore and symbols, reworked through a contemporary lens. Skulls have been polished and cherished for millennia, and in Halloween season, surrounded as we are by skeletons and carved pumpkins, I was curious to dive deeply into the underpinnings of this story.

The original version of this folk tale is deeply symbolic. The most mysterious and magical elements of the story, to my mind, have been ‘cleansed’ during Klassen’s retelling. However, the relationship between the main character, ‘Otilla’ and the ‘Skull’ remains the same across three different versions - and I’ll unpack a few points for the sake of comparison. The character of ‘The Skull’ is best described as a cherished ancestor, perhaps as a once precious elder of the community. There’s evidence that ten thousand years ago, people polished and decorated skulls, perhaps as a token of respect for deceased loved ones, or as a way to maintain a ‘connection’ with them. In each version of the story there is also a ‘Skeleton’ character, which wants possession of the ‘Skull’. The child ‘Otilla’ confronts the ‘Skeleton’ in the climax of the story and after this point, each reworking retells the folk tale in a different way.

In the original, according to Klassen, once the curse of the ‘Skeleton’ has been broken, it vanishes. At that moment, the ‘Skull’ turns into a beautiful lady dressed in white and the castle is filled with children and lovely things to play with. This lady gives everything in the castle to ‘Otilla’ before disappearing into the sky.

Another earlier version, written by Busk and edited by Rachel Harriette dates from the nineteenth century, entitled, “Otilia and the Death’s Head’ or, ‘Put your trust in providence’. It was published in London in 1871 and resonated strongly with the opening section of the well known tale ‘Cinderella’, as the young Otilla was both orphaned and resentful of her stepmother.

Overwhelmed by grief and her own vulnerability, Otilla runs away from home into the Tyrolean forest, all the while hearing her deceased father’s voice guiding her and urging her to trust in God. Hungry, cold and close to death herself, she discovers a castle and is welcomed by a speaking ‘Death Head’.

She undertakes specific tasks for the ‘Death Head’. She cooks in the kitchen, sleeps in a strange bedroom and faces her fear of the ‘Skelton’ that rattles its bones at her. However, guided by her father and trusting in God, she is resolute and fearless. The next morning, the ‘Skeleton’ is transformed into a beautiful lady dressed in white, who, having shown a lack of appreciation for all the wonderful things that life had given her, had been trapped in the castle. She turns into a dove before flying away.

Otilla displayed no fear when confronted by the ‘Skeleton’ and had broken the spell through the strength of her faith. Having inherited the castle from the lady in white, she invites her stepmother to enjoy it with her, and domestic peace and harmony are restored.

In a wonderful book called, ‘Decoding Fairytales’ by Chris Knight, Professor of Anthropology at UCL, the reader is guided through a system of symbols and signs based on the division of lived experiences as either ‘Other World’ (the world of trance, near death experiences, ceremonial masks and rebellion) or ‘This World’ (the orderly world of compliance, harmonious living and surrender). ‘Halloween’ of course is a celebration of the ‘Other World’.

To appreciate the contrast between each ‘world’ we need to think about life before the internet, telecommunications, and even the use of electricity, when moonlight was the most important source of light after sunset. The phase of the moon was believed to control not only the tides and peoples’ physical safety, but also to influence their emotions.

In this list I’ve summarised Knight’s observations of the two ‘Worlds’.

‘This World’ versus ‘Other World’

- Moon Waning versus Moon Waxing

- Midday Sun versus Eclipse

- Silence / calm versus Thunder

- Day versus Night

- Life versus Death

- Dry versus Wet

- Cooked versus Raw / Blood

- Feasting versus Hunger / Being eaten

- Emergence versus Seclusion

- Harmony versus Noise / Chaos

- Surrender versus Rebellion

- Available versus Taboo

- Human Identity versus Animal Mask

‘The Skull’ is not a story about ‘This World’. In all three versions of the tale, Otilla leaves the mundane world of her old life behind and journeys into the ‘Other World’ - the liminal world where she encounters the transition between life and death, enchantment and rebellion.

In many fairytales, a young girl finds herself lost in a forest or has been secluded in a forest (by someone in her matrilineal line). Although the forest was familiar to Otillla, as she lay in the wet snow crying, she confronted her fear of the dark, of danger and of being alone at night. Klassen allows the reader to decide whether or not it was the wind calling Otilla’s name, whereas Harriette and Busk were unequivocal that Otilla could hear her late father’s voice guiding her onwards through the darkness. The forest is both a psychological and physical barrier, carrying the risk of death and cutting her off from the safety of her domestic mundane life.

In the Harriette and Busk version of the story, Otilla is given tasks to perform. The first is to carry the ‘Death Head’. The second is to take it into the kitchen and to make a pancake. To do this she uses eggs - a universal symbol of rebirth. In Klassen’s version however, she eats a pear (carrying connotations of fertility) with ‘The Skull’, makes a fire for them both and they ‘drink tea’ (we must imagine the type of tea) by the fire. Both versions feature the fire, and in fairytales such as Hansel and Gretel or the Gingerbread Man, a kitchen fire, in a cottage in the middle of a forest traditionally cues an opportunity for children to be cooked alive.

In the Klassen version of the story, the ‘Skull’ shows Otilla a wall where ceremonial animal masks hang, explaining that they were not to be worn (i.e. taboo). However, they walk down the steps to the dungeon and look at the ‘bottomless pit’ (a familiar theme in many myths and legends, perhaps representing an ‘underworld’ or the subconscious mind). In the accompanying illustration Klassen depicts both characters wearing the animal masks, which signals that they have crossed the threshold into the ‘Other World,’ the space between life and death where it is appropriate to wear animal masks and where taboos may be broken without consequences.

Otilla has spent the first night drinking ‘tea’ and exploring the dungeon with the ‘Skull’ and now trusts sufficiently to be taken to the top of the turret. The turret, like the dungeon was traditionally a place of seclusion for girls in many fairytales. As they climb the steps from the dungeon to the balcony and move from darkness into light, we may assume that a new day, the second day of the adventure has dawned.

They remove their masks as they reach the daylight and emerge into fresh air, but then the ‘Skull’ immediately takes Otilla into the ballroom, where the sun streams in through the window. The adventure continues as they wear the ceremonial masks and dance until evening. Traditionally, wearing an animal mask simply meant acknowledging the ‘animal side’ of the self, (the side that was inhibited by social norms during domestic day-to-day life). Having danced the second day away with the ‘Skull’, Otilla makes another fire and they ‘drink tea’ in the evening. She looks into the fire, it becomes a source of inspiration and cerebral power while the ‘Skull’ tells her about the threat of the ‘Skeleton’. Otilla sleeps with the ‘Skull’ on the second night and falls into a ‘deep sleep’.

In the middle of the night, the ‘Skeleton’ appears just as predicted and tries to steal the ‘Skull’ from Otilla. The girl prevails and shows the ‘Skeleton’ that she is stronger and smarter in Klassen’s secular version (and spiritually disciplined and protected in the Harriette - Busk version).

According to Klassen, the ‘Skeleton’ chases the girl, who clutching the ‘Skull,’ leads it up to the top of the turret, throws it over the edge, and hears it shatter upon impact with the ground.

Later in the story, while the ‘Skull’ sleeps, Otilia cremates the ‘Skeleton’s’ fragmented bones. [According to Knight, fire is a traditional symbol of marriage and stands in opposition to blood, a traditional symbol of kinship.] In Klassen’s contemporary narrative, Otilla accepts an invitation to cohabit with the ‘Skull’, having made the ‘Skeleton’ disappear, and thus she emerges on day three of her adventure into a new domestic life.

In the original version and Busk’s retelling of it, the ‘Skeleton’ transforms into a beautiful lady at the end of the story, reminiscent of Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother. In both fables, the young girls have a strong affinity with the tempering and purifying power of fire, and both have lost their mothers. It would also seem that bereavement, extreme anxiety, fear and stress in a pubescent child, particularly after drinking a herbal brew such as tea, might induce such visions. But, in Klassen’s telling of the tale, these magical ‘other worldly’ elements have been removed. Instead, the ‘Skull’ offers Otilla companionship and a new home.

If the underlying elements of this story resonated, you might enjoy reading more about trance, rhyme, rhythm and language in these posts:

Rhythm, Flow, Reading Fluency and Comprehension: In extant societies, traditional life ways include hunting and gathering. For sheer survival, loud communal singing and drumming are also essential for deterring the big cats that may predate infants on the darkest of nights.

Rhythm, attention and rapid learning: Boredom and repetition generate trance-like states of attention, whereas novelty and a switch in stimulus create a rapid reset. Ultimately the attention span plays a role in predicting where and when the next reward or threat is likely to occur.

Practising poetry - The importance of rhythm for detecting grammatical structures: Rhythmical patterns in language cast beams of expectation, helping to guide and focus our attention, enabling us to anticipate and enjoy the likely flow of sound and colour in the atmosphere of the poem.

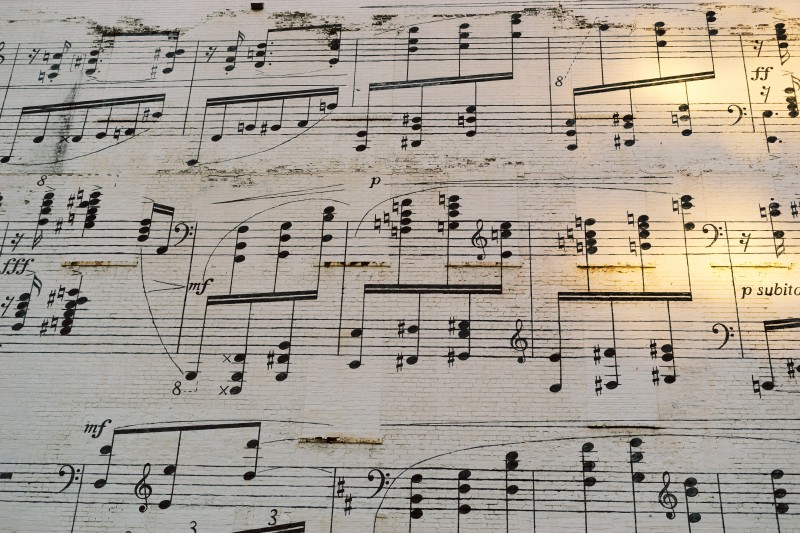

A simple view of reading - musical notation

18 October 2023

Many people think that reading musical notation is difficult. To be fair, many methods of teaching musical notation over-complicate an incredibly simple system. It’s not surprising that so many people believe musical notes are relics of the past and are happy to let them go - but isn’t this like saying books are out of date and that reading literature is antiquated? In homes all around the world, parents of all nationalities can teach children as young as three to read musical notation, as this has for a very long time become an internationally standardised system. In many schools in all parts of the UK, I’ve taught children at risk of failing the phonics screening check to read simple musical notation fluently in ten minutes. There are distinct differences in my approach and I’m sharing these here.

What is musical notation?

Musicians refer to musical notation as ‘the dots’!

These little marks written on five lines show musicians not only the musical details, but also the bigger picture - they can see the character and the style of the music by the way ’the dots’ are grouped together. Imagine you are looking at a map of your local area - you’d be able to see where buildings and streets are more densely or sparsely grouped together.

This is the skill that musicians use when they look at a page of music - it’s simply a convention for mapping musical sounds.

When was the first music written down?

Early evidence of this practice of notating music can be traced back to its archaic roots in Homer (8th century B.C.E.) Terpander of Lesbos (c. 675 B.C.E.) and Pindar (5th century B.C.E.). However, following the fall of Athens in the 5th century B.C.E., there was a break with tradition. Aristoxenus (c.320 B.C.E..) documented the cultural revolution that had taken place - the rejection of all traditional classical forms. Traditional music had been replaced by -

- a preference for sound effects imitating nature

- free improvisation

- a new fashion for lavishly embellished singing

The rejection of the old ways, including the ‘old music’ appeared to allow space for a new level of freedom. The new emphasis on individual expression rejected:

- traditional tuning systems and forms of both music and poetry

- being part of something greater than oneself

- creating something that would endure.

Musical notation, as the history shows, is less related to individual expression and more to the concept of building a musical canon - a collection of forms, styles and conventions, which are best represented in certain iconic ‘classical’ works. As such, there’s an emphasis on a standardisation of musical language, one that is mathematically well-proportioned, enduring and able to be passed on from generation to generation.

The most ancient system of musical notation, ‘neumes’ in ‘sacred western music’ was used between the 8th and 14th centuries, (C.E.) and was built upon Greek terminology. Most interestingly, the use of the apostrophe /‘/ ‘aspirate’ in the ‘neumes’ survives in today’s musical notation and shows when a musician takes a new breath or makes a slight pause. Part of the standardisation of musical notation has been that it is written on five lines.

What are the five lines called?

These lines, called ‘the stave’, show musicians whether the sounds are higher or lower in frequency (pitch). To take an extreme example, the squeak of a mouse is a high frequency sound (high pitch), and to show this frequency, the dots would be written far above the stave. Conversely, the rumble of a lorry has a low frequency sound (low pitch); to map this sound accurately, the dots would be written far below the stave. Extending the stave in this way involves writing what musicians call ‘ledger lines’.

In a central position within the spectrum of these very high and very low pitched frequencies, we have the pitch range of the human voice. Consider the sounds of the lowest male voice and the highest female voice and it’s clear that the spectrum of frequencies is still very wide. To accommodate this broad range of sounds, musicians write a different ‘clef’ sign at the extreme left of the stave. There are four ‘clef’ signs in common use: the treble (named after the unbroken boys’ voice), alto, tenor and the bass; these clefs are used by singers and instrumentalists alike. The two most commonly used are the bass and treble clefs.

- The bass clef indicates that the pitch range is suited to lower frequency sounds, matching the range of broken male voices.

- The treble clef at the extreme left of the stave indicates that the pitch range matches that of children’s and female voices.

What is the line between the notes called?

In the early 1600s, for reasons of clearer musical organisation, vertical lines started to appear in notation, which divided the music into ‘bars’ (UK) or ‘measures’ (US). For the most part, the number of beats is standardised in each bar. Keep reading to find out more about the beats!

Many of the most catchy pieces of Western music rely on simple repetition of short patterns as well as predictable beats. We perceive these to fall naturally into a regular grouping, and most melodies fall into a pattern of two, three or four beats, spread across the piece or song. Here are two recognisable examples, the first in three time, the second in four time:

- God save the King (UK) or God Bless America (US)

- Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.

Of course, we all know music that’s more complex than this. For example, traditional dance styles from all around the world are often more elaborate and combine rhythmic groupings of faster-paced patterns such as:

- 2s with 3s

- 4s with 3s

- 4s with 5s

Although these occasionally appeared in iconic classical works of the 19th century such as Mussorgsky’s ‘Pictures at an Exhibition,’ and Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, they became more commonplace in the early 20th century. These slightly irregular groupings create subtle feelings of asymmetry that is as delightful to the ear as new taste sensations are to the palette.

If there are five beats, as in ‘Take Five’ by Dave Brubeck, then after each group of five beats a vertical line shows the end of the ‘measure’ (US) also known as the ‘barline’ (UK). The bars or measures are units of time that show the organisation of the beats in the music.

Generally, ‘the dots’ and rhythms show the structure of a piece, or how it ‘works’ musically. In performance, a musician would maintain a consistent rhythmic ‘feel’. So these two essential notational elements offer a framework of predictability, which the musician reads, understands and feels:

- the number of beats in each bar

- the grouping and rhythm of the beats and notes within these bars

However, too much emphasis on the predictability and the vertical organisation of the beats can produce an effect that is wooden and robotic. Although a strict sense of rhythm and pulse (the beat) is essential for successful music making, the actual phrasing of these is more horizontal and somewhat elastic in feel.

This can work by making more of the musical tension, by stretching it in time and intensity, as well as making it louder and moving forward; it can help the listener wait in anticipation for the all-important climax and moment of release. This is incredibly effective at all levels of music making, and is known to us all in the more familiar context of telling jokes and stories, where the pacing is as important as the details.

So, this is why experienced musicians use ‘the dots’ only as a map, and allow their ‘feel’ for the rhythm, the harmony and the style to bring freedom and individuality to their expression.

What are ‘heads’ and ‘stems’?

The anatomy of ‘the dots’ tells musicians about the pitch and the time values of sounds they make.

The ‘heads’ are the oval shaped part of a note, whereas the ‘stem’ is the line that may be attached to the ‘head’. The ‘head’ of the note moves around on the stave and tells the musician about pitch and depending on whether it’s filled (black) or open (white), about time value. The ‘stem’ of the note can join with other ‘stems’ (called ‘beaming’) and tells the musician about time and emphasis.

Some teachers of musical notation are very ‘head’ focussed and have elaborate mnemonics for memorising the positions of ‘the dots’ on the stave. Here are some examples:

- All Cows Eat Grass (the spaces of the bass clef - A,C,E,G)

- Good Boys Deserve Fun Always (the lines of the bass clef - G,B,D,F,A)

- FACE (the spaces of the treble clef - F,A,C,E)

- Every Good Boy Deserves Food (the lines of the table clef - E,G,B,D,F)

The major problem with this approach is that it involves cognitive loading, as remembering these patterns rapidly absorbs a child’s finite cognitive resources. As a prerequisite for learning to read notation, these mnemonic patterns must be memorised and then applied in real time. Although this approach is not difficult for pupils with a strong working memory, it is absolutely why reading musical notation has gained its reputation for being ‘too difficult’ for some children to engage with.

Some leading musical education programmes in use today, are very ‘stem’ focussed and have elaborate time names for longer and shorter durations: ‘ta’ ‘ti-ti’ ‘tiri-tiri’ and ‘too’. Or, ‘Ta-ah’ ‘Ta’ ‘Ta-Te’ ‘Tafa-Tefe’ and there are many more to choose from.

The issue here is that the sound names are confusable because they sound so similar. Children with specific learning difficulties are likely to conflate these, and experience rhythm as confusing. This is unnecessary and easily avoided. Furthermore, it places children with weak working memory and weak sensitivity to phonemes at a considerable disadvantage.

We have completely avoided these issues in Rhythm for Reading and have opted for something simpler that does not front-load children’s attentional resources. In addition, our approach allows reading fluency to develop in the very first session.

We use simple and familiar language. ‘The dots’ are compared with lollipops and described as ‘blobs’ and ‘sticks’. Time names ‘ta’ and ‘ti-ti’ are simplified as ‘long’ and ‘quick quick’. There’s no confusion. This allows us to get on with the business of reading - fluently.

We offer professional development (CPD) that is deeply rooted in neuroscience, the development of executive function and of course, cognitive load theory. You can find out more in the following links.

Fluency, phonics and musical notes: Presenting the sound with the symbol is as important in learning to read musical notation, as it is in phoneme-grapheme correspondence. Fluent reading for all children is our main teaching goal.

Musical notation, full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection: Discover the back story… the beginning of Rhythm for Reading - an approach that was first developed to support children with weak executive control.

Empowering children to read music fluently: The ‘tried and tested’ method of adapting musical notation for children who struggle to process information is astonishingly, to add more markings to the page. Rhythm for Reading offers a simple solution that allows all children to read ‘the dots’ fluently, even in the first ten minute session.

How we can support mental health challenges of school children?

11 October 2023

The waiting lists for local child and adolescent mental health services- ‘CAMHS’ are getting longer and longer. Teachers and parents are left fielding the mental health crisis, while the suffering of afflicted children and adolescents deepens with every day that passes. Young people’s mental health challenges cannot be left to fester, as they affect their identity, educational outcomes, parental income and resilience within the wider community. Here are 10 key strategies that parents and teachers can use to support children and adolescents dealing with distressing symptoms of mental health challenges while they are waiting for professional help.

1. A calm educational environment

The size of the school seems to determine the quality of the learning environment to some extent. If every class takes place in a tranquil atmosphere, this means that every teacher takes responsibility for the ambience in every lesson. In ‘creative’ subjects such as music, art and drama, it is particularly vital that children participate in lessons where respect both for learning and for every student is maintained. An ethos of respect for every student is easier to sustain in a calm atmosphere. Children with mental health challenges are more likely to cope for longer in this setting, where they are better able to self-regulate any difficult feelings that may arise.

2. A space to talk

In a school it is important that teachers and children have spaces where they are able to discuss and resolve pastoral or academic challenges in privacy, rather than for example, in the middle of a busy corridor. This is incredibly important for the more vulnerable pupils in our communities. Those with special educational needs and disabilities need to be supported with a particular focus in terms of social, emotional and mental health. A place where children are able to ask for help or advice from the pastoral team immediately shows all pupils that this is a caring school that values their feelings, responds to their questions and most importantly, takes their mental health challenges seriously.

3. Listening from the heart

The pressure of workload on teachers is enormous, and yet according to research, teachers are more effective in the classroom when they not only show their passion for the subject, but also that they care deeply about the children they are teaching. Both these factors unfortunately can lead to teacher burn-out, which would obviously diminish their capacity to listen from the heart.

Arlie Hoschild’s ’The Managed Heart,’ discusses ‘emotional work’ as an integral but undervalued and unrecognised aspect of many public-facing roles.

Teaching is clearly one these, requiring intense and constant emotional input. Sadly, many of the best and most dedicated teachers suffer because they are so invested in pupils’ learning and personal development.

It is vital that school leaders cultivate an environment that values the well-being of teachers, protects them from abuse, prevents them from burning out and avoids unnecessary workload. Teaching can be incredibly fulfilling, but often feels all-consuming. It is therefore vital that teachers have realistic and sustainable workloads. Our teachers deserve to have time to recharge during the school day so that they are better able to support pupils’ mental health challenges, particularly if they work as part of a pastoral team.

4. Compassionate reassurance

Much has been said about empathy in recent years, but compassionate reassurance achieves a stronger outcome in less time. Compassion involves complete acceptance of the situation, as well as the capacity to hold all the challenges of that situation in mind, which is why it is easier to help students to feel emotionally ‘safe’, as they are more likely to begin to self-regulate. This involves being able to breathe deeply and slowly, feel physically more relaxed and more connected to their body, which may enable them to be better able to express their feelings and to share their concerns more openly.

5. Offering quality time with no distractions

Imagine a nine year old child, overwhelmed by a challenging situation and dealing with a mental health challenge, such as acute anxiety. One day, they feel ready to trust a teacher, to open up and to disclose their concern, but to their disappointment, the teacher must rush away to deal with something rather ‘more urgent’.

Their rational response would say, ‘Yes, emergencies happen, but my feelings are not as important as an emergency.”

At the same time, their vulnerable feelings might achieve a ‘shut down’ in their central nervous system and a dread of abandonment or rejection could trigger an acute attack of panic or anxiety or other distressing feelings and thoughts.

It is important for the child that the teacher stays physically present with them until that conversation or connection has reached a mutually agreed end point. If not, a negative spiral can quickly gain momentum if the ‘end’ of the conversation or connection feels abrupt or unplanned.

6. Practising gentle kindness

In day to day life, if we practise gentle kindness, it is obvious that we are not interested in conversations that are unkind. By walking away, we are showing that unkind remarks are not taken seriously. Gentle kindness begins in the mind, replacing judgmental thoughts with compassionate ones. It is arguably far easier to prevent mental health challenges than to treat them. Gentle kindness is a strong starting point for effective prevention.

7. Honouring the feelings

We all have feelings. Most people are uncomfortable with accepting all their feelings because difficult emotions such as shame or guilt or a belief that they are ‘not enough’ are pushed under the rug and barely acknowledged in our society.

Children and young people make comparisons between themselves and an ‘ideal’ version that they have seen online or experienced through parental scripting.

Here are a few examples of parental scripts or expectations of their child:

- To get married and have children

- To support the same sports teams as their parents

- To attend a certain school or university

- To take on the family business or join a certain profession

- To live in a particular geographical area

Sometimes this form of scripting is very ambitious and the child is expected to achieve one or several of these:

- To qualify to represent their country in an elite sports team or even in the Olympics,

- To win a scholarship to a particular school or university

- To have top quality examination results

- To break records or ‘be the first’

- To become so special and so talented that they are recognised for their accomplishments.

If these expectations are not fulfilled, harsh self-judgments and self-criticisms are likely to follow.

All of these negative beliefs, thoughts and feelings may well become so toxic that they may have a detrimental effect on the individual.

Conversely, a child who has too little support or stimulus from their family may well feel neglected and frustrated by a lack of attention and display challenging and self-pitying behaviour.

It is important to protect children from creating idealised versions of themselves. Even conscientiousness, which is often encouraged at school and is intrinsically admirable rather than harmful, can develop into an unhealthy source of anxiety and low-self-worth in certain situations.

8. Expressing the emotions

To express anger, frustration or resentment appropriately is natural and necessary. An outlet for emotions can be through sport or dancing or even music and singing. Some writers claim that anger has fuelled their best work! The response to these emotions has been carefully honed by warrior disciplines where the balance of managing and harnessing energy is the product of many years of dedicated training - for example Samuri warriors who are taught not only combative skills but also flower arranging. Cultures all around the world have found different ways to manage and express emotion in a socially accepted way. All of these practices involve allowing the body to discharge the emotions, as this is healthy.

Insufficient access to the creative curriculum means that pupils are restricted in terms of self-expression, the development of executive function, personal development and critical thinking. One appropriate way to express emotion is to dance and move, or sing and play music, allowing the body to cast off all the explosive, the aggressive and fiery feelings. Another way is to write down how these emotions feel and to really vent this on the page. These forms of physical release are very cathartic, though this needs to be done in a place, ideally out in nature - or where others won’t be disturbed!

9. Sharing worries and concerns

Young people and their parents need to share their challenges, worries and concerns. If a young person’s mental health challenges start to spiral and the situation deteriorates suddenly, this needs a swift and orchestrated response from everyone with a duty of care. It is not enough just to prioritise the children’s development of topical concepts such as, ‘resilience’, ‘growth mindset’ and ‘perseverance’. Above all, young people should not be left feeling isolated and surrounded by adults who are uncertain about what they ought to do, when facing a child who feels seriously overwhelmed, depressed or anxious.

Charities run helplines, manned by volunteers, and they train their people to offer a compassionate listening service. No one needs to suffer in isolation while they wait for professional help. As well as pastoral teams and family liaison workers in schools, there are helpline volunteers who work for charities that exist outside school. Together we can make sure that we support the families coping with child and adolescent mental health challenges every day.

10. Helpline numbers

Family Lives: 0808 800 2222

The Samaritans: 116 123

Childline: 0800 1111

NSPCC: 0808 800 5000

In an emergency dial 999.

Did some of this post resonate with your own experience?

If so, you might be interested in the important role played by rhythm in the management of stress in these related blog posts:

Education for social justice - This post sets out the mission, values and impact of the Rhythm for Reading programme in terms of reading and learning behaviour.

Rhythm, breath and well-being - This post unpacks the relationship between rhythm, breath and well-being in the context of smaller and larger units of sound, comparing the different types of breath used in individual letter names versus phrases.

Releasing resistance to reading - Discover how self-sabotaging behaviour and resistance to reading can be addressed through a rhythm-based approach.

Rhythmic elements in reading: from fluency to flow - Discover the importance of rhythm in activities that involve flow states and the way that elements of rhythm underpin flow states in fluent reading.

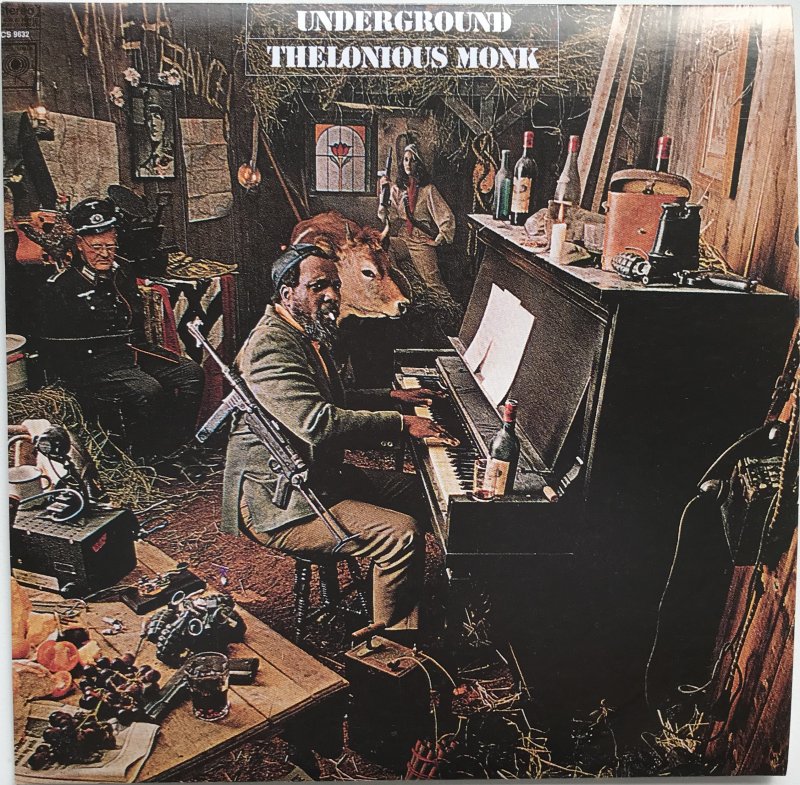

Thelonius Monk (1917-1982) A personal tribute

4 October 2023

Black History Month invites us to celebrate our differences more than ever. A knowledge-rich curriculum offers big ideas and invaluable depth of insight, but the creativity of Monk shows how knowledge can be developed to pioneer new forms and techniques. His music is unmatched in its capacity to inspire people of all ages because of its originality, which is preserved in the recordings. We are very fortunate indeed to be able to hear the playing and ideas of a musician who has led the development of an entire genre.

Having been hugely inspired by Thelonius Monk’s music, artistry and originality, I am going to express my appreciation for this exquisite musician here even though it’s impossible to do full justice to this musical icon through words alone. As a musician he is one of a kind - therefore this blog post will fall spectacularly short. But, as there is a huge gap between the struggles he endured during his lifetime and the huge amount of recognition that his artistry and humanity has received since his death, I’m going to highlight these contrasts here.

Back in the day…having graduated from the Royal Academy of Music in the late 1980s I was working with the superb musician, innovative pianist and inspirational composer, Roger Eno. I remember asking him about the artists he most deeply admired. Hearing Eno talking about Monk was so moving that I rushed out to buy a couple of albums - later that same day I listened closely to this giant of jazz.

A musician’s musician

Monk is truly a musicians’ musician. He inspires us to dig deeper and think bigger, to create with true integrity and honesty. There are forty-nine tribute albums made by admiring colleagues dating from 1958 right up to present times - the most recent was recorded in 2020. Posthumously, Monk has been awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1993), and the Pulitzer Prize (2006), but it wasn’t until 2009 that he was honoured by his home state in the North Carolina ‘Hall of Fame’.

My own first impressions, hearing this genius for the first time were a mixture of the deepest gratitude for his sincerity, and delighted astonishment in his freedom, playfulness and wit. There are other musicians who can match Monk’s dazzling piano technique - but what sets Monk apart for me, is that he took his mastery of the piano to a level of creativity that was utterly original.

Tenderness, wit and subversion

He used the piano to acknowledge tenderness, to dismantle and reweave others’ works and he delightfully subverted iconic works by other composers.Take for example, ‘Criss-Cross’ - in this track, Monk mocks Stravinsky’s ballet, ‘The Rite of Spring’ and we hear the saxophone and the piano calling out the famous opening motif played by the solo bassoon. Later Stravinsky’s ‘primal’ cross rhythms emerge through the composition, repurposed by Monk to restore percussive vibrancy to the nuanced rhythmic feel of these patterns.

Even more vivid perhaps, is ‘North of Sunset’. This track nods to the traditional blues which appear and disappear fleetingly, like shadowy outcasts in the glare of Monk’s quirky grammatical purity and the lean contours of his modern jazz style.

Architecture and musical form

Then there’s Monk’s relationship with depth and perspective. The best musical compositions of any genre have an architectural quality, with clearly defined form and proportions unfolding through sound. And yet in Monk we hear musical structures projected with the clarity of a hologram. For instance in the track, ‘Between the devil and the deep blue sea’ (based on Harold Arlen’s work of 1931) there’s infinite perfection in the proportions. Monk matches structural precision with a vivid portrayal of the title. At the end of his solo, he pushes the music over the edge and into vertiginous cascades of notes, shaking up our depth perception. Then there’s a curious restlessness that smoulders and smokes, depicting the title of the track perfectly.

Mimicry and magic

Other tracks that come to mind with a similarly dazzling precision are ‘Locomotive’ in which the breadth of the ‘groove’ evokes a driving mechanical feel, punctuated by crunchy chordal edginess. ‘Tea for Two’ is joyful in a suitably restrained and respectful way, but then unexpectedly explodes into a delightful sound world, mimicking the clatter of porcelain teacups and saucers. Elsewhere there are fleeting references to Schubert’s ‘Trout’ Quintet, with Monk conjuring witty and magical surprises.

Contemplative mood

It’s not all about wit and clever jokes. One of the things I most admire most about Monk as a performing artist is his use of space and silence. In ‘Japanese Folk Song’ the lyrical melody is stripped back to an emaciated dry skeleton, devoid of unnecessary or extra sounds and yet this transformation makes it all the more potent. Sharing with us the nakedness of the folk song, he displays his extraordinary gift for working with the essence of melody and the spaces between notes - in this case the chasms between chords, which achieve alchemy in real time.

In these tracks he shows his powers in dismantling a melody, a musical style, and a genre, then rebuilding it, but with the precision of a watchmaker whose fingers were immediately able to align the sound with whatever his mind envisioned.

Creativity flowing from ambiguous moments

After my own thoroughly classical training, encountering the exuberance of his playing reminded me what music was really for and how our creativity is the most authentic gift humans can offer to one other. For an illustration of this, in ‘We See,’ the abrupt musical fissures in the seemingly conventional introduction metamorphose into an extraordinary spaciousness. We soon discover that this ambiguity is the precursor, the necessary foundation from which a richer harmonic language emerges. Complementing the depth and complexity of the harmonies, we hear Monk’s ability to stretch and mould the elasticity of cross-rhythms and lilting flexibility of the phrases. Monk was always searching for the edges of extremes within the logic of balance, but in this track he appears to explore the boundaries of what’s possible in a more playful and yet still profound way.

Necessity as the mother of invention

When researching this post, I was sad to read about his struggles in life. He had even endured being beaten and unlawfully detained by the police. In every setback he displayed resilience and dignity. Surely the sophistication of his playing developed in part from sheer necessity: he had to create this unique style so that his music became his intellectual property - it was essentially impossible to copy. Listening to the melody in Monk’s ‘Bolivar Blues’ however, the ‘hit’ theme song ‘Cruella De Vil’ from Disney’s ‘1001 Dalmatians’ clearly shows more than a ‘homage’ to Monk. And he didn’t receive the full recognition that he deserved during his lifetime. Had Monk been awarded the Grammy and the Pulitzer while still alive, I would like to think that he’d have played more in the later years of his life and suffered fewer mental health issues.

Outcast or Genius?

Just as most books about reading development don’t mention rhythm, books about music tend not to mention Monk. But, Steven Pinker in ‘How the Mind Works’, is unequivocal under the heading ‘Eureka!’

And what about the genius? How can natural selection explain a Shakespeare, a Mozart, an Einstein, an Abdul-Jabbar? How would Jane Austen, Vincent van Gogh, or Thelonius Monk have earned their keep on the Pleistocene savannah?

Here’s part of Pinker’s brilliant answer to his own question:

But creative geniuses are distinguished not just by their extraordinary works, but by their extraordinary way of working; they are not supposed to think like you and me.

If you enjoyed reading about this giant of jazz, here are links to related posts about the value of music and creative subjects in the curriculum - (with a light touch of political opinion). As Brian Sutton-Smith once said,

The opposite of play is not work. The opposite of play is depression.

Creativity, constraints and accountability - Creativity is hardwired within all of us and there’s a playfulness in the ‘what if…’ process which guides an unfolding of impulse, logic and design.

The Power of Music – This post discusses Professor Sue Hallam’s ‘Power of Music’ - a document that reviews more than 600 scholarly publications on the effect of music on literacy, numeracy, personal and social skills to support the need for of music in the education of every child.

Knowledge, culture and control - Is history cyclical? As we move rapidly into climate crisis, artificial intelligence (AI) and a school curriculum dominated by STEM subjects, this post questions the present lack of emphasis on critical thinking and creativity.