The Rhythm for Reading blog

All posts tagged 'Rhythm-for-Reading'

When Rhythm & Phonemes Collide

7 November 2022

Have you ever taught a child with weak phonological awareness? The differences between sounds are poorly defined and individually sounds are swapped around. A lack of phonological discrimination could be explained by conflation. Conflation, according to the OED is the merging of two or more sets of information, texts, sets of ideas etc into one.

One of the most fascinating aspects of conflation is that it can happen at different levels of conscious awareness. So, for example teenagers learning facts about physics might conflate words such as conduction and convection. After all, these terms look similar on the page and are both types of energy transfer.

Younger children might conflate colours such as black and brown as both begin with the same phoneme and are dark colours. The rapid colour naming test in the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing reveals such conflation. For instance, a child I assessed once as part of a reading intervention conflated brown and green. Any brown or green square in the assessment was named ‘grouwn’ (it rhymed with brown). She had conflated the consonant blends of ‘br’ and ‘gr’ and invented a name for both colours.

In the early stages of reading, conflation can underpin confusion between consonant digraphs such as ‘ch’ and ‘sh’. Another typical conflation is ‘th’, and ‘ph’ (and ‘f’). In all of these examples, the sounds are similar and they differ only on their onset - the very beginning of the sound.

A child with sensitivity to rhythm is attuned to the onsets of the smallest sounds of language. In terms of rhythmic precision, the front edge of the sound is also the point at which the rhythmic boundary occurs. Children with a well-developed sensitivity to rhythm are also attuned to phonemes and are less likely to conflate the sounds. Logically, cultivating sensitivity to rhythm would help children to detect the onsets of phonemes at the early stages of reading. Stay tuned for Part 2 and a free infographic..

Empowering children to read musical notation fluently

4 November 2022

Schools face significant challenges in deciding how best to introduce musical notation into their curriculum. Resources are already stretched. Some pupils are already under strain because they struggle with reading in the core curriculum. The big question is how to integrate musical notation into curriculum planning in a way that empowers not only the children, but also the teachers.

The tried and tested ways of teaching musical notation are best suited to pupils who process information with ease. Traditionally, piano teachers begin with mnemonics for the notes that sit on the lines of the stave EGBDF (Every Good Boy Deserves Favour) GBDFA (Good Boys Deserve Fun Always) and for the notes that sit on the spaces FACE (Face) and ACEG (All Cows Eat Grass). Many teachers use these mnemonics to introduce a series of line notes and / or space notes all at once, which creates a heavy cognitive load.

What about all the children who struggle to process information, reading with ease and fluency?

Well-intentioned efforts to adapt musical notation for children who struggle to process the mnemonics, involve adding more information and increasing the cognitive load.

What is going on here?

Music teachers want children to enjoy making music and to have fun producing sounds on their instruments and they hope that in time, reading notation will gradually become familiar and easier to read. Until that point, music teachers add extra information to remind the child of the letter names of the notes. In the same vein, they often add numbers representing the finger patterns, to remind the child how to produce sounds on the instrument.

Soon enough, the page is cluttered with markings and the child has to select which ones to read.

These markings are intended as a quick fix, aiming to keep the child engaged. But of course the child relies on the letters, or the numbers, or both instead of reading the actual notes. This approach sets the child up to fail in the sense that they do not learn to read notation at all and even worse, assume that it is too difficult for them.

What could teachers do differently to support children who do not process information with ease and fluency?

A more inclusive approach would limit the cognitive load on children’s reading - which is what we do in the Rhythm for Reading Programme. Rather than teaching all the notes at once, we focus on just a few notes and develop fluency (and fun) in reading right from the start. Instead of learning the musical notes at the same time as playing musical instruments, which adds to the cognitive load, we simply use our feet, our hands and our voices, as we believe these are our most natural musical instruments.

Group learning in a structured programme supports the development of fluency, because the children are nurtured by the ethos of working together. Teamwork in combination with rhythm is an effective way to build fluency in reading, and acts as a catalyst for accelerated progress.

Teaching Musical Notation and Inclusivity

31 October 2022The teaching and learning of musical notation has become a hot new topic since its appearance in the Ofsted Inspection Framework published in July 2022.

For too long, musical notation has been associated with middle class privilege, and yet, if we look at historical photographs of colliery bands, miners would read music every week at their brass band rehearsals. Reading musical notation is deeply embedded in the industrial roots of many towns.

As a researcher I’ve met many primary school children from all backgrounds who wanted to learn to read music and I’ve also met many teachers who thought that reading music was too complicated to be taught in the classroom.This is not true at all! As teachers already know the children in their class and how to meet their learning needs, I believe that they are best placed to teach musical notation.

There are many perceived problems associated with teaching musical notation in English primary schools, and a top one is that many teachers do not read music. It is so easy to address this issue. Using the techniques of the Rhythm for Reading Programme, teachers can learn to read music fluently in time with a backing track (think Karaoke) in five minutes. Yes - five minutes!

Empowering school staff to read music offers a cost effective and strategic approach to raising standards in reading across the curriculum.

Stay tuned for the next post, when I’ll discuss ways to meet all of these challenges.

Rhythm, breath and well-being

10 October 2022

Breath is an important part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. We use our voices as a team in different ways and this engages our breath. In the early stages of the programme we use rapid fire responses to learn the names of musical notes and our breath is short, sharp and strong - just like the sounds of our voices. Even in the first session of the programme we convert our knowledge of musical notes into fluent reading of musical notation and when we do this our breath changes. Instead of individual utterances, we achieve a flowing coherent stream of note names and our breath flows across the length of the musical phrase for approximately six seconds. This time window of between five and seven seconds is a universal in human cultures. Did you know that the majority of poems are organised rhythmically into meaningful units of between five and seven seconds in duration?

A long slow exhalation is associated with calming the nervous system, even though the energy in the Rhythm for Reading session is playful and the sense of teamwork is energising. The unity between the children and teachers taking part in the programme fosters a sense of belonging which further boosts well-being alongside the calming effect of the long slow exhale.

When I first meet teachers, they often share that they feel anxious about reading musical notation, but one of the most beneficial aspects of taking part, is that our long slow exhale as a group is actually an effective way to sooth anxiety. The smiles at the end of the first musical phrase show a powerful release of emotional tension through the unity of rhythm and breath.

Rhythm, attention and rapid learning

3 October 2022

There are many different forms of attention. Neuroscientists have studied the development of cognitive attention in children as well as the different types of attention that we experience. Boredom and repetition generate a trance-like state of attention, whereas novelty and a switch in the stimulus generate a shift and a rapid reset of attention. The attention span exists to protect us, to feed us and to ensure that our genes succeed us in future generations. This is why the attention span is adaptable and can be trained to become longer or shorter using reinforcements such as rewards or threats. Ultimately, the attention span is involved in predicting when and where the next reward or threat will take place.

If a chid has experienced a threatening situation such as a war zone, they are likely to flinch in response to loud noises and their attention is likely to be highly vigilant, having been trained by the environment to monitor potential threats. A chid raised in a calm and enriched environment is likely to have fostered a natural curiosity for the world around them and to have interacted in reciprocation with it. Conversational turns in such an environment are the rhythmic hallmark of social interactions, and according to researchers contribute to emotional well-being and language development (Zimmerman et al., 2009).

The Rhythm for Reading programme offers an opportunity to move children away from a vigilant state, to a rhythmically responsive form of attention that involves reciprocation and builds receptivity and stamina. The attention system is dynamic and is particularly responsive to setting and emotional set point. If a child was threatened repeatedly at school, for example by a bully, then vigilance in the attention system would affect the child’s learning to some extent.

By the same token, it’s important that Rhythm or Reading sessions take place in the same place, on the same day of the week and at the same time of day to establish the regularity of exposure to rewarding experiences. Knowing where and when positive experiences occur, such as feelings of personal safety, social connection, a boost to well-being, engagement with rewarding patterns and calming breath work, which are nurtured during Rhythm for Reading sessions is important. The anticipation and experience of weekly Rhythm for Reading sessions enables a child’s attention system to recognise the sessions as a ‘real’ part of their environment. A consistent pattern in the children’s lives enables a deeper sense of anticipation and supports rapid learning during the programme.

Zimmerman, E.J., Gilkerson, J.,Richards, J. A., Christakis, D.A. Xu, D., Gray, S., Yapanel., U. (2009) Teaching by listening: The importance of adult-child conversations to language development. Pediatrics, 124 (1), 342-349, doi: 10.1542/peds 2008-2267

Fluent reading is not just our goal, it’s our foundation

20 September 2022

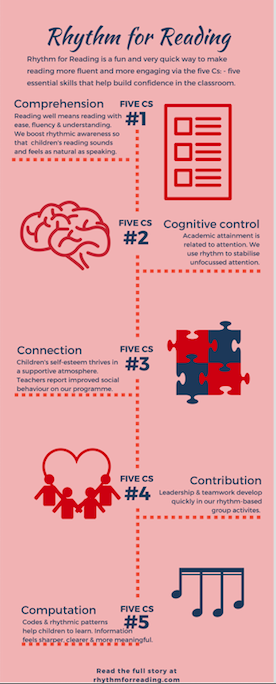

I believe that together, as educators on a mission to make a difference, we must raise standards in reading. The Rhythm for Reading programme offers a mechanism to achieve this. It provides a cumulative and structured approach that supports inclusive teaching and learning.

For instance, there is absolutely no need to break down tasks. We strive to lighten the cognitive load on working memory as an inbuilt feature, and this is why pupils experience the satisfaction of reading musical notation fluently in the very first week.

Although most curriculum subjects encourage progress in speaking or writing or problem-solving, our approach is multi-sensory: we develop children’s rhythmic sensitivity in a range of different ways.

On the one hand, the materials and resources are designed to sustain the fluency of the children’s reading, and on the other hand we adapt the level of challenge by working with the children’s ears, eyes, voices, hands and feet in ever-changing combinations.

The Programme engages working memory with sensitivity. It strengthens cognitive control across the ten weeks by gradually increasing demands on cognitive flexibility week by week. In each weekly session, the pupils build up their repertoire of routines and techniques. Ease is maintained all the while, supporting fluency and control in the execution of all the tasks. Most importantly of all, the primary goal is to support an ethos of inclusivity by maintaining the pupils’ emotional security at all times.Fluency is established at the start and it is maintained right through to the end of the ten weeks. Fluent reading is not just our goal, it’s our foundation.

Rhythm and Reading Comprehension 1/5

29 April 2018

‘To be understood - as to understand’ from the prayer of St Francis captures a profound truth: we are at our happiest when we feel truly understood by others. This feeling of mutual understanding strengthens communities and generates an aura of certainty at the core of each individual’s character. The ability to understand exists in all of us, but can easily be obscured by doubt, worry or fear. Removing worries, doubts and fears leads to clarity –as Johnny Nash put it, “I can see clearly now the rain has gone…”. The same principle applies to reading comprehension. The songlike qualities of speech (i.e. prosody) come to life in children’s voices when they are able to read with ease, fluency and understanding.

In the Simple View of Reading, reading comprehension is described as the ‘product of’ skilled decoding and linguistic comprehension (Gough & Tumner, 1986). The recent focus on oracy (for example Barton, 2018) highlights a focus in some schools on linguistic comprehension. According to researchers, the proportion of children beginning school with speech, language and communication needs is estimated at between 7 and 20 per cent (McKean, 2017) and unfortunately, communication issues carry a risk of low self-esteem and problems with self-confidence (Dockerall et al., 2017).

In the Gough & Tunmer model, the term ‘product of’ seems a little vague. I like to think that ‘product of’ refers to the flexible quality found in skilled reading as well as the dynamic integration of natural language with the alphabetic code. At first, beginning readers struggle to accommodate words and sentences of a variety of shapes and lengths, but as they become more skilled, they ease into a state of flexible, responsive reading, which leads to being able to read sentences whilst processing meaning at the same time. What is even more remarkable about this process is that reading with this wonderful flexibility takes place within distinct time constraints.

The time constraints are a kind of rhythmic signature for language comprehension as well as music and are biologically determined (Long, 2006). Each and every line of a song, poem or musical phrase typically lasts for 3-5 seconds. This brief ‘window’ is our subjective sense of the present moment (Gerstner & Fazio, 1995). In a song, a poem or a musical phrase, this moment is packed with messages and meanings – relating information about feeling, being or doing. The rhythm of reading in any language is very flexible indeed, but it is underpinned by this constant ebb and flow of units of meaning every 3-5 seconds. Becoming aligned with this natural flow of meaning helps children to read words, phrases and sentences with ease, fluency and understanding and also to anticipate words and phrases prior to reading them.

The importance of this rhythmic ebb and flow of meaning cannot be overstated and is a core part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. The programme uses music rather than words to develop rhythmic sensitivity, so it is suitable for children and young people who need a sharp ‘boost’ in reading comprehension, language and communication skills, phonological awareness or cognitive control, whether attending mainstream or special schools.

Barton, G “Teachers should encourage pupils to speak up – and should remember to do so themselves TES News https://www.tes.com/news/teachers-should-encourage-students-speak-and-remember-do-so-themselves Retrieved on 29.4.2018

Dockrell, Julie Elizabeth, et al. “Children with Speech Language and Communication Needs in England: Challenges for Practice.” Frontiers in Education. Vol. 2. Frontiers, 2017.

Gerstner, Geoffrey E., and Victoria A. Fazio. “Evidence of a universal perceptual unit in mammals.” Ethology 101.2 (1995): 89-100.

Gough, Philip B., and William E. Tunmer. “Decoding, reading, and reading disability.” Remedial and special education 7.1 (1986): 6-10.

Long, M. “Stamping, clapping and chanting: An ancient learning pathway?” Educate Journal, 3, 1, (2006) 11-25

McKean, Cristina, et al. “Language Outcomes at 7 Years: Early Predictors and Co-Occurring Difficulties.” Pediatrics(2017): e20161684.

Catch-Up and Catch-22

14 April 2018

Academic achievement relates strongly and reciprocally to academic self-concept, for example in English and Maths (Schunk & Pajares, 2009) and also reading (Chapman & Tumner, 1995); moreover the importance of motivation increases as perceptions of reading difficulty increase (Klauda et al., 2015). So reading catch-up can also feel as if it’s a catch-22 situation. To resolve this issue, Hattie (2008) recommended that teachers teach self-regulating and self control strategies to students with a weak academic self-concept: ‘address non-supportive self-strategies before attempting to enhance achievement directly’ (Hattie, 2008; p.47).

Peeling back the layers on the self-concept literature, various models and analogies are available (Schunk, 2012). Hattie’s highly effective analogy of a rope captures rather vividly the idea of the congruence of the core self-concept as well as the multidimensionality of intertwining fibres and strands that are accumulated via everyday experiences (2008, p.46). The rope image supports the idea that a particular strand applies to maths, whereas a completely different strand applies to reading and another one for playing football and so on.

The relationship between self-concept and academic achievement is reciprocal (Hattie, 2008) and also specific to each domain (Schunk,2012). Therefore, strengthening self-concept for reading supports achievement in reading, while strengthening self-concept for maths supports maths skills. It is very difficult to strengthen low self-concept in a specific domain before addressing achievement in that area, unless introducing a completely new approach. It is important that the new approach supports self-strategies as well as directly building strength in domain-relevant skills. The Rhythm for Reading programme meets both of these requirements.

Rhythm for Reading works as a catalyst for confidence and reading skills and therefore lifts a negative reciprocal relationship (catch-22 situation) into a positive cycle of confidence and progression. This programme is effective as a reading catch-up intervention because it offers a fresh and dynamic approach, which perfectly complements to traditional methods. Instead of reading letters and words, pupils read simplified musical notation for ten minutes per week. Consequently, they are practising skills in decoding, reading from left-to-right, chunking small units into larger units, maintaining focus and learning, as well as developing confidence, self-regulation and metacognitive strategies all the while.

The musical materials used in the Rhythm for Reading programme have been specially written to be age-appropriate and to secure pupils’ attention, making the effortful part of reading much easier than usual. In fact, throughout the programme, the cognitive load for reading simple music notation is far lighter than for reading printed language, enabling an experience of sustained fluency and deeper engagement to be the main priority. As these case-studies show, this highly-structured approach has had huge successes for low and middle attaining pupils, who were able to read with far greater ease, fluency, confidence and understanding after only 100 minutes (ten minutes per week for ten weeks).

Chapman, J. W., & Tunmer, W. E. (1995). Development of young children’s reading self-concepts: An examination of emerging subcomponents and their relationship with reading achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 154–167.

Hattie, J. (1992). Self-concept. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hattie, John.(2008) Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Routledge.

Klauda, Susan Lutz, and John T. Guthrie. “Comparing relations of motivation, engagement, and achievement among struggling and advanced adolescent readers.” Reading and writing 28.2 (2015): 239-269.

Pintrich, P.R. and Schunk, D.H. (2002). Motivation in education: Theory research and applications (2nd edition) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Rogers, C.R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, inter-relationships as developed in the client-centered-framework. In S. Kock (Ed) Psychology: A study of a science, Vol.3, pp.184-256 New York, McGraw-Hill.

Schunk, D. H. and Pajares, F. (2009). Self-efficacy theory. In K. r. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 35-53). New York:Routledge.

Schunk, D.H. (2012) Learning theories: An educational perspective, 6th edition, First published 1991 Boston: Allyn & Bacon, Pearson Education Inc.