The Rhythm for Reading blog

All posts tagged 'Rhythm-for-Reading-programme'

Child development in 2024: Learning versus hunger

3 January 2024

I had planned to find a light-hearted piece of new music education research for the first post of 2024 and maybe a few fun facts. I considered a study on the benefits of chanting, another on whether rats feel groovy (and yes, rats do feel the groove), but eventually I chose a new piece of research on the benefits of singing to infants because it drilled down into a possible relationship between rhythmic movement and expressive vocabulary development (Nguyen and colleagues, 2023).

At the same time, I considered recent topical pieces on child development and education in the mainstream media. Suddenly, this post became much heavier as it was destined to contrast the challenges of struggling families against the privileges of those who shape music education as research participants.

In recent weeks, there has been coverage on the rapid rise of ‘baby banks’ (Chloë Hamilton, The Guardian Newspaper). These are like food banks, but specialise in providing free nappies, baby formula, clothes and equipment. We have 200 branches in the UK and just as the Christmas holidays were about to start, there was also a piece about headteachers reporting malnourishment among their pupils (Jessica Murray, The Guardian Newspaper).

Having delivered the Rhythm for Reading programme in schools that also function as community food banks, and having seen children faint from hunger while at school, I am in no doubt that nothing can be more important to a civilised and caring society than children’s physical well-being - hungry children cannot learn anything at all.

In a balanced and caring society in which there is time to sing, to tell stories, and to enjoy family life without grinding hardship, music has its own role to play. People feel more inclined to engage socially and to look out for each other when they feel safe. From this perspective, is music important or not? When people need food to survive, food is more important than music. If people want to build a balanced and cohesive community, both music and food are fundamental for establishing trust and strong relationships whether in family life, business and trade, or diplomacy.

How do we know that music is important for child development?

According to decades of research, infants are exposed to music every day, particularly as their caregivers sing to them to entertain, to soothe and to share emotions with them. Even in utero, at 35 weeks gestational age, foetuses show more movement to musical sounds than to speech sounds, whereas at two months of age, an infant coordinates their gaze with the ‘beat’ of their caregiver’s singing. It is clear that music captures their attention and in this post I’ll point out how it seems to further their development.

What is infant-directed singing?

Infant-directed singing (compared with singing in general) is characterised by a slower tempo, more regularity in the pulse and a relatively wide range in terms of louder and quieter volume. The features of live infant-directed singing include positive emotional expression, accompanied by gestures and facial animation. In play songs there are also actions such as bouncing, jigging or sudden playful movements, whereas slower calming rocking movements characterise the soothing nature of lullabies.

How do infants respond to infant-directed singing?

As infants develop, they begin to adapt their rhythmic movements to coordinate with the rhythmic structure of music that they listen to, but the reasons for this are not well-understood. In terms of language development, years of research on infant listening has indicated that infants are sensitive to the rhythm, volume fluctuations and comprehensibility of speech, including sensitivity to these in nursery rhymes. Recent findings showed that newborn infants’ ability to track fluctuations in singing predicted their expressive language at 18 months.

What is the mechanism?

Researchers have found that these early life experiences of infant-directed singing endow children with sensitivity to the tempo (pace), changes in melodic patterns, harmony and rhythmic patterns of musical extracts. There’s been a recent focus on whether fluctuations in volume map directly onto the listening child’s brain activity, and most recently the same approach has been investigated in listening infants. The researchers refer to the term ‘neural tracking’ and by this they mean the extent to which brain activity is synchronised (entrained) with the features of the singing.

Who took part?

The research involved two different groups of mothers who had expressed an interest in taking part in this research. These mothers aged between 29-39 years, were highly educated: more than 86 per cent of them held university degrees and more than half of them (55 per cent) played a musical instrument, whereas one fifth (20 per cent) had time for themselves and sang in a choir. The authors did not explain the working status of these women, and the amount of time they each spent with their infant, whether some of the infants were enrolled in a crêche, or whether the mothers had chosen to return to work.

During the initial part of the research, all of the infants were seven months of age, lived in German speaking households and were without developmental delay. Across the two groups of participants, nine infants in total were excluded from taking part because of ‘infant fussiness’. This is a common practice in experiments of this kind; this means that the findings reflected the behaviour of infants who were well-adjusted enough to cope with the research protocols (such as wearing an EEG bonnet). The research involved testing the infants’ responses to play songs and lullabies at seven months of age. Then at twenty months, the researchers collected data detailing the children’s expressive language development.

In psychological research, it is important to justify the sample because the characteristics of these individuals are likely to shape the findings to a large extent. It is very difficult to draw broad conclusions about the relevance of infant-directed singing to vocabulary development from this particular group of people, when it is well known that parents’ educational level is a strong predictor of expressive language development in young children (Hart and Risley, 1995).

What is the vocabulary gap?

Expressive vocabulary development and the vocabulary gap became very topical almost thirty years ago when Hart and Risley (1995) conducted their work on vocabulary development in different social groups in America. This groundbreaking study involved analysing 1,300 hours of observations. An average child in a wealthier family heard 2,000 words during an hour, whereas a child from a family receiving welfare, heard 600 words in one hour. By the age of three, children from wealthier backgrounds had twice as many words in their productive vocabulary.

The wider impact of the Hart and Risley research

This finding had a powerful impact and the UK government launched the Sure Start initiative in 1998. Funding became available to enrich the lives of new parents through antenatal classes, postnatal support, parenting courses, nutritional advice, and provided supportive opportunities for very young children living in the poorest neighbourhoods in the UK up to the age of four. This scheme was successful in terms of physical health outcomes; it reduced harsh parenting practices and hospitalisations among children at age eleven. Sure Start Centres lost two thirds of their funding in 2010 and a relatively small number of these centres serve deprived communities.

Will we continue to see malnourished children in 2024?

Unlike Sure Start Centres, which were run in dedicated buildings, the baby banks are grassroots projects and some are set up as a series of tents in deprived rural areas. In the article by Chlöe Hamilton, mothers, who seek help from baby banks cannot afford to heat their homes and feed their children. Moreover, these mothers opt not to feed themselves, even though they are pregnant.

It is in these rural areas that head teachers are very concerned about rising levels of malnourishment. The are seeing children’s teeth falling out, their pupils have bowed legs and stunted physical growth. In some schools, as many as half of the pupils receive free school meals and a free breakfast, which is supplied by the charity ‘Magic Breakfast’. School leaders are also very concerned about children who do not qualify for free school meals, as the lunch they bring to school contains nothing more than cheap sugary snacks.

It is poignant that the first baby bank was started shortly after the banking crisis in 2008. Now there are 200 banks in the UK and over fifty branches are run by one charity, ‘Baby Basics’. According to a London-based charity, ‘Little Village’ twelve per cent of parents needed to visit the baby banks for children’s clothes and toys in the run up to Christmas, 2023.

It is not possible for children to learn when they are hungry and stressed. The lessons of Sure Start apply here. Jessica Murray’s article highlighted how hunger leads to dysfunction in the family relationships and the consequences of this are far reaching according to Dr Sarah Hanson, Associate Professor in Community Health at University of East Anglia:

“There’s evidence that not getting enough to eat causes low mood and anxiety, and often leads to stricter discipline in households. For children, their behaviour worsens and it has been linked to increased asthma diagnoses, as well as significantly higher use of emergency care.”

How is the study on infant-directed singing relevant to this situation?

Although the findings of the infant-directed singing study are more relevant to families of similar social characteristics to the participants: German speaking and highly educated, the most important finding is that infants are listening to their caregivers.

Most interesting perhaps, was that when the researchers manipulated the acoustic features of the singing - the pitch, the tempo, the beat - there was no significant effect on the infants’ neural tracking and this finding is a very inclusive one - infants listen, no matter how strange the singing may sound.

In both lullabies and playsongs, researchers found that infants’ rhythmic movement during the singing was strongly related to their neural tracking. This association between rhythmic movement and neural tracking was statistically significant. Lullabies were notable because they elicited stronger neural tracking - but that is not surprising, given that lullabies are hypnotic by their nature.

The researchers also found that infants’ neural tracking of play songs at seven months was significantly related to their expressive vocabulary at twenty months. This was not a product of chance, (95 percent confidence level). By seven months, these children had already developed playful interactions (involving infant-directed singing and rhythmic movement) in a way that was priming them for productive language. This chimes with the Hart and Risley research and really illustrates the importance of a supportive environment, particularly in the earliest months of an infant’s life.

If your enjoyed this post, keep reading!

Conversations, rhythmic awareness and the attainment gap

In their highly influential study of vocabulary development in the early years, Hart and Risley (1995) showed that parents in professional careers spoke 32 million more words to their children than did parents on welfare, accounting for the vocabulary and language gap at age 3 and the maths gap at age 10 between the children from different home backgrounds.

Narrowing the attainment gap through early reading intervention

Wearing my SENCO hat, I strongly believe that the principle of early reading intervention (as opposed to waiting to see whether a learning difficulty will ‘resolve itself’ over time), and a proactive approach, can narrow the gaps that undeniably exist when children enter primary school.

In 2013, I adapted the Rhythm for Reading programme so that I could put in place urgently needed support for a group of Year 1 and Year 2 children, who struggled with their school’s phonics early reading programme. Their school had already seen impact of the programme on key stage two children, so the leadership team were keen to extend its reach.

The backdrop to reading is the space in the child’s mind.

In a recent post, I referred to Ratner and Bruner’s (1977) article on ‘disappearing’ games such as peekaboo. The article is clear that play of this type contributes to an infant’s ability to engage and interact not only with the game, but with the world around them as well. The playful and even joyful energy of peekaboo accompanies each of these four stages of learning

Gamification, Social Exchange and the Acquisition of Language

According to neuroscientists, repeated use of specific neural pathways catalyses the maturity of the neural structures through a process known as myelination. Referring back to Ratner and Bruner’s question about the ‘nature’ of early ‘disappearing’ games, it appears that language learning during infancy and early childhood coincides with spontaneous and joyful social interaction with an accompanying sense of intrinsic reward. This arguably contributes to successful social interaction throughout life.

References

Hamilton, C., ‘A day at the baby bank: ”I feel at ease here, because I’m not the only one struggling”, The Guardian Newspaper, published on 19.12.23 accessed 30.12.23

Hart, B. And Risley, T.R. (1995) Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children, Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Murray, J, ’Children have bowed legs’: hunger worse than ever, says Norwich School, The Guardian Newspaper, published 21.12.23 accessed 30.12.23

Nguyen et al (2023) Sing to Me Baby: Infants show neural tracking and rhythmic movements to live and dynamic maternal singing, Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 64, 101313

Supporting children with a ‘fuzzy’ awareness of phonemes and other symptoms consistent with dyslexia

13 December 2023

I’m often asked whether the Rhythm for Reading Programme helps children ‘diagnosed’ with dyslexia. As I have not done a study - and by this I mean a randomised controlled trial - with children ‘labelled’ with this specific learning difficulty, I rely on anecdotal evidence to answer the question. Every time a child, identified with dyslexia asks me whether I can help them, I ask them to tell me if and when they notice a change in their reading. To date, the children diagnosed with dyslexia have told me that they have seen improvements in reading, writing and even spelling. Some have reported that they are better able to focus in class and some have also noticed an improvement in their ability to ‘understand the question’ in maths lessons. These anecdotal data are a positive indication that Rhythm for Reading does indeed help children with a diagnosis of dyslexia.

Working memory capacity

Dyslexia is a broad umbrella term that is often associated with other specific learning differences, such as (but not limited to) dyspraxia and ADHD and ADD. These so-called ‘co-morbidities’ make it difficult to study dyslexia at scale in a scientific way because there are so many differences among children labelled with this particular specific learning difficulty.

Having supported many children with specific learning difficulties in my role as special educational needs coordinator (SENCO) in two secondary schools and one junior school, it became obvious that every child I worked with had a specific learning difficulty that was unique to them. And yet, practitioners and teachers in these schools were able to support a wide range of learning differences, by using a particular set of ‘dyslexia friendly’ tools. This was made possible because all of these children had one issue in common - their limited working memory capacity.

Working memory capacity describes the extent to which a person can hold and manipulate information in mind. Saying the alphabet backwards is a simple example of a task involving working memory. Removing the ’t’ sound from the word ‘winter’ (to make the word ‘winner’) is another simple example of a task that involves maintaining and manipulating information in working memory. A person with dyslexia would find such a task tiring and also frustrating. Imagine how challenging it would be to hold only three words in working memory when faced with a task that involved ‘writing in sentences’. Children with a specific learning difficulty often find that as they start to make marks on the page, the words in their mind fade or fragment. For these children, every hour of every day spent in the classroom, presents a new mountain to climb. Their working memory capacity always lets them down, no matter how hard they try to focus their attention. As a child, I experienced this too, but all of these problems disappeared when I was about eleven years old and joined a children’s orchestra.

A diagnosis of ‘severe dyslexia’

The diagnosis of dyslexia came in my early forties when I faced a sharp increase in stress in my personal life. Many people with dyslexia describe having ‘good days’ and ‘bad days’ and the effect of stress on working memory in particular would account for this. One morning, at 7.45 am, as I was about to begin teaching, to my astonishment I discovered that I could not read. The middle three letters of every word were superimposed and all I could see were smudges of ink on the page. Unable to read a single word, I assumed that this was a visual convergence problem and managed to squint out of the corner of my right eye for a few days until I was seen by an ophthalmologist. One week later, I was able to read again with the help of a conspicuous pair of dark green lenses.

A well-qualified psychologist conducted my dyslexia assessment one month later and declared in her report that I would struggle to complete secondary level education. This was nonsensical as I had a PhD and soon after that point had papers published in academic journals. A good psychological assessment on the other hand, can be a helpful guide. It can identify areas for particular focus and can empower an individual as they learn to manage their specific learning difficulty - otherwise what is the point? After four months, my eyes had returned to normal and I was able to read without the special spectacles, but I still have them tucked away in a drawer.

‘Fuzzy’ phonemes

If we turn to auditory problems faced by people with dyslexia, there are two interesting things to consider. One is fuzzy phonemes. Phonemes are the smallest sounds of language. If we break the sound wave of a phoneme down into its beginning, middle and end, this can help us to think about the very first part of the sound. Among children with dyslexia, there is a lack of perceptual clarity at the front edge of a phoneme, which scientists refer to as the ‘rise-time’. This means that children with dyslexia are significantly slower to detect the differences between phonemes. This is why rhythm can provide what is needed. Improving rhythmic awareness involves shifting the child’s attention to the front edge of each musical sound of a rhythmic pattern, and as the children are chanting, there is increased emphasis at the front of the phonemes too.

Here are a few of the phonemes that children with dyslexia struggle to differentiate. Looking at this list, it is obvious that there is insufficient sensitivity to the timbral qualities of the sounds as well as the ‘rise time’.

- ‘p’ and ‘b’

- ‘sh’ and ’ch’

- ‘f’ and ‘v’

- ‘f’ and ’s’

- ‘pr’ and ‘br’

- ‘tr’ and ‘chr’

Confusable sounds and conflated ideas

The second thing to think about is a tendency to conflate the sounds of words and similar concepts. Conflation is a reasonable and even logical coping strategy. It is a smart way to ‘cut corners’ as an efficiency drive within the context of a limited working memory. Many children with dyslexia conflate the colours black and brown and name those colours interchangeably. I worked once with a child who had conflated green, black and brown and referred to all three at ‘grown’ (rhyming with brown).

Are there different types of dyslexia?

Essentially, the label refers to a specific difficulty regarding the processing of words. It is described as ‘specific’, because it exists even though the individual has sufficient verbal and non-verbal intelligence to read and write and spell words and has been taught appropriately.

Attempts to classify types of dyslexia as ‘deep’, ‘superficial’, ‘phonological’ and so on are interesting, because all of these manifestations of dyslexia can be found in schools, but at the heart of this, children who have symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of dyslexia lack sufficient sensitivity to rhythm and phonemes. The idea that rhythm is a cure for dyslexia oversimplifies the complexity of this specific learning difficulty. The anecdotal evidence indicates that a rhythm-based intervention can support dyslexia, but I would add the caveat that it must be delivered in a supportive learning environment that also nurtures the child’s self-esteem. The child’s emotional safety must be established before sensitivity to rhythm and the smallest sounds of language can develop.

It is also important to adapt lessons to be more ‘dyslexia friendly’. For example, younger children can benefit from using holistic, multi-sensory approaches, such as the activities that underpin the structure of the Rhythm for Reading Programme. Here are some case studies to illustrate progress made by children, identified by their school as requiring additional support in reading.

If you enjoyed this post, click on these links to read more.

Phonics and stimulation of the vagus nerve: How long and short vowel sounds differ

It is essential to identify any pupil who is falling behind the pace of the school’s phonics programme and to put effective support in place, but the quality of such support must withstand scrutiny. A certain amount of cognitive bias has been identified and found to disadvantage the lowest attaining children.

When phonics and rhythm collide part 1

A child with sensitivity to rhythm is attuned to the onsets of the smallest sounds of language. In terms of rhythmic precision, the front edge of the sound is also the point at which the rhythmic boundary occurs. Children with a well-developed sensitivity to rhythm are also attuned to phonemes and are less likely to conflate the sounds.

When phonics and rhythm collide part 2

Vowel sounds carry interesting information such as emotion, or tone of voice. They are longer (in milliseconds) and without defined edges. Now imagine focussing on the onset of those syllables. The consonants are shorter (in milliseconds), more sharply defined and more distinctive, leaving plenty of headspace for cognitive control. If consonants are prioritised, information flows easily and the message lands with clarity.

Phonemes and syllables: How to teach a child to segment and blend words, when nothing seems to work

There is no doubt that the foundation of a good education, with reading at its core, sets children up for later success. The importance of phonics is enshrined in education policy in England and lies at the heart of teaching children to become confident, fluent readers. However, young children are not naturally predisposed to hearing the smallest sounds of language (phonemes). Rather, they process speech as syllables strung together as meaningful phrases.

What can we do to support the development of reading fluency?

22 November 2023

All children from all backgrounds need to learn to read fluently so that they can enjoy learning and fully embrace the curriculum offered by their school. A key challenge for schools is identifying an appropriate intervention that effectively supports reading fluency - a necessary part of a coherently planned, ambitious and inclusive curriculum that should meet the needs of all children.

The children who lag behind their classmates in terms of fluency are not a homogenous group. Although time-consuming and costly, one-on-one teaching is essential for those who struggle the most. However, short, intensive bursts of rhythm-based activity (Long, 2014) have been found to give a significant boost in reading fluency in the context of a small group intervention. This approach is an efficient use of resources as it supports those children who struggle with fluency in ten weekly sessions of only ten minutes.

An evidence-based, rigorous approach to the teaching and assessment of reading fluency leads to increases in children’s confidence and enjoyment in reading. Whilst logic might suggest that the difficulty level of the reading material is a barrier to the development of reading fluency, manipulating the difficulty level of the text does not directly address the underlying issue.

Reading fluency involves not only letter to sound correspondence, but also social reciprocity through the medium of print and therefore the orchestration of several brain networks. The social mechanisms of a child’s reading become audible when the expressive and prosodic qualities in their voice start to appear. This is why a more holistic child-centred perspective is helpful - it allows children to experience learning to read as a playful, rather than a pressured experience.

The pressure felt by children with poor reading fluency arises because of inattention and distractibility, as well as variability in their alertness, which pull them off-task. Compared with their classmates, these children are either more reactive and volatile in social situations, or quieter, and more withdrawn. Our rhythm-based approach uses small group teaching to reset these behaviours, by supporting these children into a more regulated state. Working with the children in this way helps them to adapt to the activities, to adjust their state and to regulate their attention within a highly structured social situation.

What are the key components of reading fluency?

Different frameworks describe fluency in different ways. From a rhythm-based perspective, the components of expression, flow and understanding are the most important. There is one more to consider - social engagement with the author - the person who wrote the printed words. The extent to which the child reads with expression, flow and understanding reflects the degree of social engagement while reading. One of the ways to accomplish this is to free the volume and range of the voice by encouraging a deeper involvement with the text. It’s easy to achieve this in books that invite readers to exaggerate the enunciation of expressive or onomatopoeic words.

Flow in reading fluency

The flowing quality of fluent reading shows that the child has aligned the words on the page with the underlying grammatical structure of the sentences. This sounds more complicated than it actually is and doesn’t need to be taught, because children activate these structures in the first eight months of life, when they acquire their home language. Accessing these deep structures during reading enables them to feel the natural rhythm in the ebb and flow of the language. However, there are many different styles of both spoken and printed language, as each one may have a different rhythmic feel. Feeling the rhythmic qualities of printed language is inherently rewarding and motivating for both children and adults: it allows the mind to drop into a deeper level of engagement and achieve an optimal and self-sustaining flow state.

Understanding in reading fluency

There is one prerequisite! Understanding printed language requires motivation to engage. Let’s call this the ‘why’. It involves a degree of familiarity with the context and a basic knowledge of vocabulary, which are both necessary to stimulate the involvement of long term memory, as well as a desire to become involved in the narrative. Many books introduce us to new concepts, vocabulary and contexts, but the ‘why’ must act as a bridge between what is already known and the, as yet, unknown. This ‘why’ compels us to read on.

About the ‘Why’

In a conversation there is a natural alignment between expression, flow and understanding. The energy in the speaker’s voice may signal a wide range of expressive qualities and emotions which help the listener to understand the ‘why’ behind the narrative, as well as keeping them engaged and encouraging reciprocation. The ‘why’ in the narrative is arguably the most important element in communication as it conveys a person’s attitude and intention in sharing important information about challenges or changes in everyday life and the experiences of individual characters - the staple features of many storylines or plots.

‘Handa’s Surprise’ by Eileen Browne

So, in Eileen Browne’s beautiful telling of ‘Handa’s Surprise,’ a humorous book about a child’s journey to her best friend’s village, the reader learns about the names of the fruits in her basket, the animals that she encounters and becomes curious to learn what happens to Handa as she walks alone in southwestern Kenya.

It isn’t necessary for young children to know the names of the fruits, such as ‘guava’, ‘tangerine’ or ‘passion fruit’. Despite the irregularities of words such as ‘fruit’ and ‘guava’ (and the need to segment ‘tangerine’ with care to avoid ‘tang’) children understand the story, having been introduced to the new (unknown) vocabulary in the (known) context of ‘fruit’. The child’s long term memory offers up the background knowledge of ‘fruit’ as a broad category, but adds the names of the new fruits under the categories: ’food-related’ and ‘fruit’ for use in future situations in their own life.

The new vocabulary in the story enriches children’s knowledge of fruit, but the ‘why’ of this tale is the bigger question… Will Handa complete her journey safely? Empathy for, and identification with Handa elicits, (subconsciously), an increase in the reader’s curiosity and brings further focus to the mechanisms of reading fluency. Once each new word has been assimilated into the category of ‘fruit’, reading fluency is self-sustaining and driven by plot development and empathy for the main character. Having read this story (and many others) with children, I have become aware that reading fluency must become closely aligned with the rule-based patterns of grammar, as these enable irregular words such as ‘fruit’ and ‘guava’ to be quickly assimilated into the flow of the story.

‘Jabberwocky’ by Lewis Carroll

A more famous and exaggerated example of this effect is Lewis Carroll’s ‘Jabberwocky’. Many of the novel ‘words’ invented by Carroll for this poem must be assimilated into the reader’s vocabulary. The process is much the same for made up, as it is for unfamiliar words. Long term memory offers up categories of animals and their behaviour, relative to the evocative sounds of ‘words’ such as, ‘slithy’, ‘frumious’ and ‘frabjous’.

The grammatical structure of each line of verse is kept relatively simple, allowing the narrative to feel highly predictable, as it is clearly supported by the regular metre. The repetitive feel of the ABAB rhyme structure guides the reader to use the conventions of grammar in anticipating, and thus engaging with the unfolding, yet somewhat opaque narrative.

Together, the features of repetition, rhythm and predictability strengthen coherence, so that the words are chunked together in patterns based on the statistically learned probabilities of spoken language. Deeper grammatical structures that sit beneath these rhythmic patterns are logic-based: they offer up meaning and interpretation based on micro-cues of nuanced emphasis, intensity and duration within the fluent stream of language, whether spoken or read.

Why is reading fluency important?

Reading fluency is important for three reasons and these also act as drivers of motivation and learning.

- Reading fluency brings the rhythmic patterns of language into alignment with deeper grammatical structures that are necessary for meaning-making.

- These structures - which are probabilistic - bring into awareness the most likely next words, phrases, and developments in the story. These are not based on pure guesswork, but reflect the reader’s understanding of the genre, the context and text-specific cues.These include appraising the shape of the word, and automaticity in recognising the shapes of letters (graphemes), words and their corresponding sounds (phonemes). These cues are necessary, but not sufficient to orchestrate fluent reading.

- Reading fluency supports children as they expand their vocabulary.

The majority of studies show that:

- A strong relationship exists between vocabulary size and social background,

- Up to ninety per cent of vocabulary is not encountered in everyday speech, but in reading,

- Vocabulary is particularly important for text comprehension,

- Children’s books tend to include more unfamiliar words than are found in day-to-day speech.

The first two mechanisms work together symbiotically to anticipate, adapt and adjust to what is coming up next in printed language, similar to when we hear someone speaking. The third mechanism changes a child’s perspective on life. Teachers and parents need to expose children to printed language, including the unfamiliar and orthographically irregular words, simply because it is through reading fluency that these words are assimilated into a child’s lexicon.

How do you measure reading fluency?

Listening is key to measuring reading fluency. If a child practises a sentence by repeating it at least three times, there should be a natural shift in the level of engagement. In a child struggling with reading fluency, four attempts may be necessary. Here is an example of the process of refinement through repetition.

- A beard hoped up to my wind….ow.

- A b….ir…d h…o….p…p….ed up to my w…in, win…..d…..ow.

- A b…ear…ir…d, b..ird, BIRD…. hopped up to my wind…ow (long pause) window.

- A bird hopped up to my window.

The pivotal moment was when ‘b-ird’ became BIRD. This would have sounded louder because the child’s voice would have become clearer once the (known) category ‘bird’ was activated in their long term memory and the meaning behind the word was understood. Long term memory offered up the strong likelihood of ‘hopped’ in relation to the category ‘bird’ and this helped the child to extrapolate that the final word must be a ‘thing’ to hop towards. This was not guesswork, nor was it an exclusive reliance upon phoneme-grapheme correspondence, but an alignment of 1. long term memory (including probabilistic language processing) with 2. visual recognition of letters and knowledge of the sounds they represent (including a degree of automaticity).

Reading fluency can be measured in terms of engagement, expression, flow and understanding and in the Rhythm for Reading programme we specialise in transforming children’s reading at this deep (subconscious) level. Children move from relying on unreliable decoding strategies (because the English language doesn’t follow the regularities of letter to sound correspondence), through to full alignment with the language structures that underpin their everyday speech. Once this shift has taken place, the children are able to enjoy interacting with books and they also grow in confidence in other areas of learning and social development.

We have helped many hundreds of children to engage with reading in this natural and fluent way using our rhythm-based approach, which is delivered in only ten weekly sessions of ten minutes. There are almost a thousand case studies confirming the relationship between our programme and transformations in reading fluency. Click the link to read about selected case studies.

If you have enjoyed reading this post, why not sign up for free weekly ‘Insights’. You will be among the first to know about special offers and our new online programmes!

If reading fluency is of interest, you may enjoy these posts

Reading fluency: Reading, fast or slow?

Schools ensure that all children become confident fluent readers, so that every child can access a broad and balanced curriculum. Fluent reading underpins a love of reading and is an important skill for future learning and employment and it also enables children to apply their knowledge and skills with ease.

Reading fluency again - looking at prosody

Prosody is closely associated with skilled reading, being integral to fluency and a predictor of achievement in reading accuracy and comprehension. Prosody is not taught, but it is a naturally occurring feature of competent reading. The words on the page may be arranged in horizontal lines, but a good reader transcends the visual appearance of the words, allowing them to take on a natural, flexible and speech-like quality.

Many teachers and head teachers have remarked on the improvement in their pupils’ reading fluency, so it seemed important to try to capture what has been happening. Of course, there are different ways to define and to measure reading fluency, but here is a snapshot of what we found when using two types of assessment.

References

Eileen Browne (1995) Handa’s Surprise, Walker Books and Subsidiaries.

Long, Marion. “‘I can read further and there’s more meaning while I read’: An exploratory study investigating the impact of a rhythm-based music intervention on children’s reading.” Research Studies in Music Education 36.1 (2014): 107-124.

Musical notation, a full school assembly and an Ofsted inspection

10 January 2023Many years ago, I was asked to teach a group of children, nine and ten years of age to play the cello. To begin with, I taught them to play well known songs by ear until they had developed a solid technique. They had free school meals, which in those days entitled them access to free group music lessons and musical instruments. One day, I announced that we were going to learn to read musical notation. The colour drained from their faces. They were agitated, anxious and horrified by this idea.

No! they protested. It’s too hard.

After all these lessons, do you really think I would allow you to struggle? I asked them.

The following week, I introduced the group to very simple notation and developed a system that would allow them to retain the name of each note with ease, promoting reading fluency right from the start. This system is now an integral part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. It was first developed for these children, who according to their class teacher, were unable either to focus their attention or to learn along with the rest of the class.

After only five minutes, the children were delighted to discover that reading musical notation was not so difficult after all.

I can do it! shrieked the most excitable child again and again, and there was a wonderful atmosphere of triumph in the room that day.

After six months, the entire group had developed a repertoire of pieces that they could play together as a group and as individuals. It was at this point that Ofsted inspected the school. The Headteacher invited the children to play in full school assembly in the presence of the Ofsted inspection team. They played both as a group and as soloists. Each child announced the title and composer of their chosen piece, played impeccably, took applause by bowing, and then walked with their instrument to the side of the hall. At the end of the assembly the children (who were now working at age expectation in the classroom) were invited to join the school orchestra and sit alongside their more privileged peers. The Ofsted team placed the school in the top category, ‘Outstanding’.

If you would like to learn more about this reading programme, contact me here.

Rhythm, phonemes, fluency and luggage

12 December 2022

Louis Vuitton began his career in logistics and packing, before moving on to design a system of beautiful trunks, cases and bags that utilised space efficiently and eased the flow of luggage during transit. He protected his designer luggage using a logo and geometric motifs. The dimensions of each piece differed in terms of shape and size, and yet it was undeniable that they all belonged together as a set - not only because they matched in appearance, but also because each piece of the set could be contained within a larger piece. In fact, the entire set was designed to fit into the largest piece of all.

The grammatical structures of language and music share this same principle that underpinned the Louis Vuitton concept. In a language utterance, the tone, the pace and the shape of the sound waves carry a message at every level - from the smallest phoneme to the trajectory of the entire sentence.

The shapes of individual syllables are contained within the shapes of words. The shapes of words are contained within the shapes of phrases and sentences. Although these are constantly changing in real time - like a kaleidoscope, the principle of hierarchy - a single unit that fits perfectly within another remains robust.

In music, the shapes of riffs, licks, motifs, melodies and phrases are highly varied, but the hierarchical principle remains a constant here too. The musical message is heard in the tone, the pace and the shape of the smallest and largest units of a musical phrase.

Just as Vuitton used design to create accurate dimensions at every level of his luggage set, the same degree of precision is also achieved at a subconscious level in spoken language and in music. A protruding syllable, the wrong emphasis or inflection can throw the meaning of an entire sentence out of alignment. A musical message is similarly diluted if a beat protrudes, is cut short or is lengthened, because the length and shape of an entire phrase is distorted.

Arguably, the precise dimensions in Vuitton’s groundbreaking designs reflect a preference for proportion and balance that also underpins human communication involving sound. Our delight in the consummation of symmetry, grammar and rhyme is present in the rhythm of language and also in music. At a conceptual level, it is ratio that unifies the Vuitton designs with language and music, and it is ratio that anchors our human experience in interaction with one another and our environment.

This concept of ratio, as well as hierarchical relationships and the precision of rhythm in real time underpin the Rhythm for Reading programme. Think of this reading intervention as an opportunity to reorganise reading behaviour using a beautiful luggage set, designed for phonemes, syllables, words and phrases. It’s an organisational system that facilitates the development of reading fluency, and also reading with ease, enjoyment and understanding.

Three factors to take into account when assessing reading comprehension.

28 November 2022

In the Rhythm for Reading Programme, progress in reading is measured using the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability 2nd edition revised (NARA II). Reading comprehension is one of three standardised measures in this reading assessment. There are many good assessments available, but I’ve stuck with this one because it offers three supportive features that I think are particularly helpful. If you are unfamiliar with NARA II, let me paint a picture for you. Detailed illustrations accompany each passage of text. For a child grappling with unfamiliar vocabulary or weak decoding, the illustrations offer a sense of context and I’ve seen many children’s eyes glance over to the illustration, when tackling a tricky word.

In practice, children come out of class one at a time for individual reading assessment. Each reading assessment lasts twenty minutes on average. The main advantage of an individual assessment over a group assessment is that the assessor is permitted to prompt the child if they get stuck on a word. In fact the assessor can read the tricky word after five seconds have elapsed, which helps the child to maintain a sense of the overall narrative. This level of support is limited by the rigour of the assessment. For example, an assessor would not give the definition of a word if a child asked what it meant and sixteen errors in word accuracy on a single passage of text signals the end of the assessment.

This particular individual format is more sensitive that all others in my opinion, because it minimises the influence of three cognitive factors on the scores.

Factor one: There is minimal cognitive loading of working memory as the child can refer back to the text when answering questions. In other words, they do not need to remember the passage of text, whilst answering the questions. This approach prevents a conflation between a test of comprehension and a test of working memory. Children may score higher on NARA II if working memory is likely to reach overload in other reading test formats, for example, if the child is required to retain the details of the text whilst answering comprehension questions.

Factor two: There is no writing involved in NARA II, so a child with a weak working memory achieves a higher score on the NARA II than on other formats if writing in sentences is a specific area of difficulty for them.

Factor three: The assessor keeps the child focussed on the text. This makes a big difference if a child is likely to ‘zone out’ frequently and to experience scattered or fragmented cognitive attention. In this instance, a child with weak executive function is more likely to achieve a higher score on the NARA II than on other formats, because of the support given to scattered or fragmented attention.

At the end of the ten weeks of our reading intervention, children have achieved higher scores not only in NARA II, but also in the New Group Reading Test and the Suffolk Reading Scales. Many children experience gains in cognitive control as well as reading fluency and comprehension.

Rhythm, flow, reading fluency and comprehension

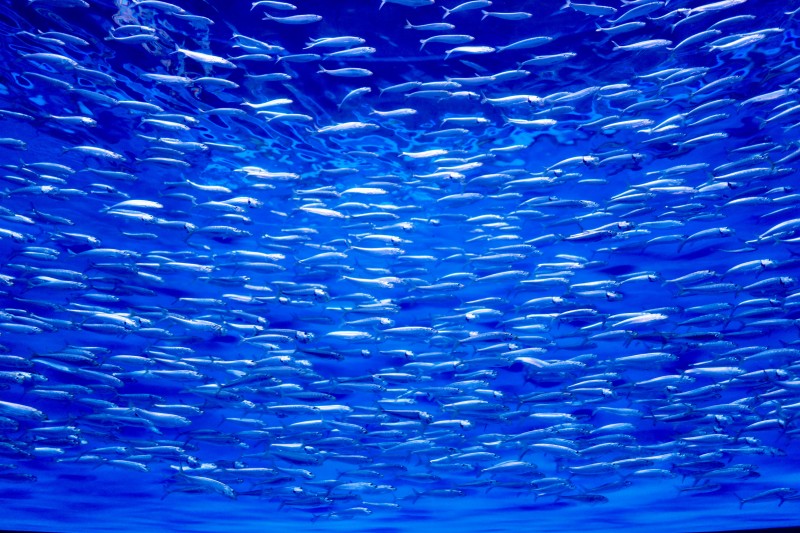

20 November 2022In extant societies that live as hunter-gatherers, loud communal singing and drumming creates the illusion of a large coherent entity, large enough to deter big cats that predate on the darkest of nights. Arguably, communal singing through the night may be a key human survival strategy. There’s evidence to show that feelings of cooperation and safety are experienced when humans sing and dance together and many people report being able to sustain hours of music making, when in a group. Other species such as birds and fish deter predators by forming a large mass of synchronised movement patterns. Murmurations form before birds roost for the night and shoals of herrings achieve the same mesmeric effect when they are pursued by predators such as sea bass.

Detecting rhythm and moving in time creates a trance-like state, which allows the perception of time to shift such that the focus narrows onto staying in time with the beat of others, nearby. Anticipating what will happen next is a key element of this narrow focus. If we break that down, it involves anticipating the regularity of the beat, whether within simple or complex rhythmic patterns.

Reading for pleasure can be framed as a social situation in which the reader synchronises with the writer’s style. To ‘get into a book’ we need to achieve a flow state - which is a trance-like state resulting in relatively narrow focus. This means everything else, but the book (or screen) disappears from our attention. The entranced state induces reading fluency and comprehension, drawing us deeper into the text where we might feel that we have ‘escaped’. To escape into a book means to suspend our usual sense of who we are, having become engrossed with the text, perhaps by empathising with the characters, or simply by synchronising with the flow of the writing. A close level of synchrony between the words on the page, and our anticipation of what comes next is arguably similar to the defensive mechanism of creating a larger entity in real time because it involves losing the usual sense of self and becoming part of something larger than day-to-day life - which brings us all the way back to communal singing and dancing.

Sensitivity to rhythm is all around us

14 November 2022A few weeks ago, in an inset session at a wonderful school with beautiful inclusive approaches in their group teaching, I mentioned that rats have the same limbic structures as humans. The limbic system is the part of the brain that deals with our mammalian instincts. These keep us in tune with social information, such as social status and hierarchy, protecting and nurturing our children, bonding with sexual partners and managing affiliation. It’s a logical assumption that if we share these limbic structures, rats like humans should be able to keep time with a musical beat - or their equivalent of that. So, it was no surprise to learn that Japanese researchers have shown that rats can indeed bob along and keep time with a musical beat.

It was back in the 1980s, when American scientists first discovered the genes that determined the rhythm of the mating song of fruit flies. If we think of rhythm as a musical trait exclusive to humans, these findings in rats and flies are simply amusing, novel or entertaining. On the other hand, the bigger picture behind these findings would suggest that the natural world is inherently structured by environmental and behavioural patterns organised by rhythm. If we think of rhythm as a system of ratios, proportions and repetition, then the math of rhythm is obvious. There are cycles and rhythmic flows in tides and weather systems and indeed, migration patterns follow these cycles. In individual organisms, as well as in shoal, pod, flock and herd movement, rhythmic patterns underpin locomotion and communication. Even a human infant’s stepping reflex is organised around the inherent rhythmic systems that we share with many other species.

We humans are particularly happy when our stylised rhythms achieve a hypnotic effect, for example in Queen’s ‘We will rock you,’ - one of the songs used by the Japanese scientists to detect the sensitivity to rhythm in rats. Halfway through the Rhythm for Reading programme, this same rhythmic pattern appears and is always greeted with enthusiasm by teachers and children as a fun part of the reading intervention. Look out for the next post, which explains the connection between hypnotic rhythm, flow states, reading fluency and reading comprehension.