The Rhythm for Reading blog

All posts tagged 'Reading'

Where has all the chanting gone?

2 October 2020

When I watched the announcements about lockdown on March 23rd 2020 from a hard metal seat in Glasgow International Airport, I’d already made ten trips to Scotland and it felt so frustrating that the project would be interrupted when we were so close to its completion. Throughout the lockdown and the summer months, I hoped very much that we would have a chance to salvage and finish off the work. In the past two weeks it has been an absolute privilege to return to the schools with ‘refresher sessions’ and follow-up testing. So much has changed. The teachers vigorously spray, clean and ventilate the classrooms. Everyone is vigilant and determined to keep their community safe. It is obvious that this goal is shared and held dear by all. Even young children immediately take all their books and pencils with them when they sit on the floor while their tables and chairs are disinfected. Absolutely nobody needs to be reminded to do this.

In one of the schools, particular spaces are filled with food and clothing. The leadership team came into the school every single day of the lockdown, as well as throughout the summer months to keep everyone on track; teachers worked face-to-face with the children throughout this period. Stunning new displays made by the parents now explode out from the staffroom walls and thank you cards are pinned to the noticeboard of a beautiful new community room.

Rhythm for Reading has been modified to keep everyone safe. I visit only one school in a single day and wear a mask. The children remain in their ‘bubbles’ when they take part, and stand at least two metres away from me. In between each session, I ventilate and vigorously disinfect the teaching area. Of course, there is plenty of time for cleaning as each Rhythm for Reading session is, as always, only ten minutes in duration. Actually, this level of flexibility fits in very well with the dynamic teaching that I’m seeing in the schools - and the children are loving that they are being taught in small groups and in an increasingly nuanced way.

Robust, energetic chanting has always been an important part of the Rhythm for Reading programme, but chanting, like singing is strictly prohibited. For quite some time I have been resigned to mothballing the programme for this reason. Eventually however, a neat solution popped into my mind. With a bit of experimentation, I realised that it is possible to vocalise safely and precisely, whilst keeping the volume level below that of normal speaking. All that is required to make this modification fun, is a little imagination. Most children know how to squeak like a mouse - these high pitched sounds are made in the throat and involve minimal breath - far less than speech. So, my solution has now been ‘road-tested’ by the squeaky teams in Scotland and I’m happy to have found a safe and new way to offer the programme without diluting it.

I would like to say a huge thank you to these children, teachers and school leaders for the opportunity to come back and complete the programme. It has been utterly inspiring, humbling and uplifting to visit your schools these past two weeks.

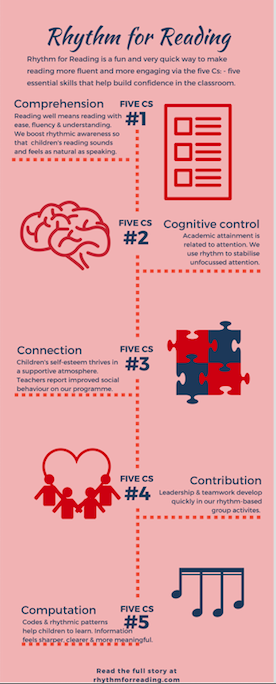

Rhythm and Reading Comprehension 1/5

29 April 2018

‘To be understood - as to understand’ from the prayer of St Francis captures a profound truth: we are at our happiest when we feel truly understood by others. This feeling of mutual understanding strengthens communities and generates an aura of certainty at the core of each individual’s character. The ability to understand exists in all of us, but can easily be obscured by doubt, worry or fear. Removing worries, doubts and fears leads to clarity –as Johnny Nash put it, “I can see clearly now the rain has gone…”. The same principle applies to reading comprehension. The songlike qualities of speech (i.e. prosody) come to life in children’s voices when they are able to read with ease, fluency and understanding.

In the Simple View of Reading, reading comprehension is described as the ‘product of’ skilled decoding and linguistic comprehension (Gough & Tumner, 1986). The recent focus on oracy (for example Barton, 2018) highlights a focus in some schools on linguistic comprehension. According to researchers, the proportion of children beginning school with speech, language and communication needs is estimated at between 7 and 20 per cent (McKean, 2017) and unfortunately, communication issues carry a risk of low self-esteem and problems with self-confidence (Dockerall et al., 2017).

In the Gough & Tunmer model, the term ‘product of’ seems a little vague. I like to think that ‘product of’ refers to the flexible quality found in skilled reading as well as the dynamic integration of natural language with the alphabetic code. At first, beginning readers struggle to accommodate words and sentences of a variety of shapes and lengths, but as they become more skilled, they ease into a state of flexible, responsive reading, which leads to being able to read sentences whilst processing meaning at the same time. What is even more remarkable about this process is that reading with this wonderful flexibility takes place within distinct time constraints.

The time constraints are a kind of rhythmic signature for language comprehension as well as music and are biologically determined (Long, 2006). Each and every line of a song, poem or musical phrase typically lasts for 3-5 seconds. This brief ‘window’ is our subjective sense of the present moment (Gerstner & Fazio, 1995). In a song, a poem or a musical phrase, this moment is packed with messages and meanings – relating information about feeling, being or doing. The rhythm of reading in any language is very flexible indeed, but it is underpinned by this constant ebb and flow of units of meaning every 3-5 seconds. Becoming aligned with this natural flow of meaning helps children to read words, phrases and sentences with ease, fluency and understanding and also to anticipate words and phrases prior to reading them.

The importance of this rhythmic ebb and flow of meaning cannot be overstated and is a core part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. The programme uses music rather than words to develop rhythmic sensitivity, so it is suitable for children and young people who need a sharp ‘boost’ in reading comprehension, language and communication skills, phonological awareness or cognitive control, whether attending mainstream or special schools.

Barton, G “Teachers should encourage pupils to speak up – and should remember to do so themselves TES News https://www.tes.com/news/teachers-should-encourage-students-speak-and-remember-do-so-themselves Retrieved on 29.4.2018

Dockrell, Julie Elizabeth, et al. “Children with Speech Language and Communication Needs in England: Challenges for Practice.” Frontiers in Education. Vol. 2. Frontiers, 2017.

Gerstner, Geoffrey E., and Victoria A. Fazio. “Evidence of a universal perceptual unit in mammals.” Ethology 101.2 (1995): 89-100.

Gough, Philip B., and William E. Tunmer. “Decoding, reading, and reading disability.” Remedial and special education 7.1 (1986): 6-10.

Long, M. “Stamping, clapping and chanting: An ancient learning pathway?” Educate Journal, 3, 1, (2006) 11-25

McKean, Cristina, et al. “Language Outcomes at 7 Years: Early Predictors and Co-Occurring Difficulties.” Pediatrics(2017): e20161684.

Catch-Up and Catch-22

14 April 2018

Academic achievement relates strongly and reciprocally to academic self-concept, for example in English and Maths (Schunk & Pajares, 2009) and also reading (Chapman & Tumner, 1995); moreover the importance of motivation increases as perceptions of reading difficulty increase (Klauda et al., 2015). So reading catch-up can also feel as if it’s a catch-22 situation. To resolve this issue, Hattie (2008) recommended that teachers teach self-regulating and self control strategies to students with a weak academic self-concept: ‘address non-supportive self-strategies before attempting to enhance achievement directly’ (Hattie, 2008; p.47).

Peeling back the layers on the self-concept literature, various models and analogies are available (Schunk, 2012). Hattie’s highly effective analogy of a rope captures rather vividly the idea of the congruence of the core self-concept as well as the multidimensionality of intertwining fibres and strands that are accumulated via everyday experiences (2008, p.46). The rope image supports the idea that a particular strand applies to maths, whereas a completely different strand applies to reading and another one for playing football and so on.

The relationship between self-concept and academic achievement is reciprocal (Hattie, 2008) and also specific to each domain (Schunk,2012). Therefore, strengthening self-concept for reading supports achievement in reading, while strengthening self-concept for maths supports maths skills. It is very difficult to strengthen low self-concept in a specific domain before addressing achievement in that area, unless introducing a completely new approach. It is important that the new approach supports self-strategies as well as directly building strength in domain-relevant skills. The Rhythm for Reading programme meets both of these requirements.

Rhythm for Reading works as a catalyst for confidence and reading skills and therefore lifts a negative reciprocal relationship (catch-22 situation) into a positive cycle of confidence and progression. This programme is effective as a reading catch-up intervention because it offers a fresh and dynamic approach, which perfectly complements to traditional methods. Instead of reading letters and words, pupils read simplified musical notation for ten minutes per week. Consequently, they are practising skills in decoding, reading from left-to-right, chunking small units into larger units, maintaining focus and learning, as well as developing confidence, self-regulation and metacognitive strategies all the while.

The musical materials used in the Rhythm for Reading programme have been specially written to be age-appropriate and to secure pupils’ attention, making the effortful part of reading much easier than usual. In fact, throughout the programme, the cognitive load for reading simple music notation is far lighter than for reading printed language, enabling an experience of sustained fluency and deeper engagement to be the main priority. As these case-studies show, this highly-structured approach has had huge successes for low and middle attaining pupils, who were able to read with far greater ease, fluency, confidence and understanding after only 100 minutes (ten minutes per week for ten weeks).

Chapman, J. W., & Tunmer, W. E. (1995). Development of young children’s reading self-concepts: An examination of emerging subcomponents and their relationship with reading achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 154–167.

Hattie, J. (1992). Self-concept. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hattie, John.(2008) Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Routledge.

Klauda, Susan Lutz, and John T. Guthrie. “Comparing relations of motivation, engagement, and achievement among struggling and advanced adolescent readers.” Reading and writing 28.2 (2015): 239-269.

Pintrich, P.R. and Schunk, D.H. (2002). Motivation in education: Theory research and applications (2nd edition) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Rogers, C.R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, inter-relationships as developed in the client-centered-framework. In S. Kock (Ed) Psychology: A study of a science, Vol.3, pp.184-256 New York, McGraw-Hill.

Schunk, D. H. and Pajares, F. (2009). Self-efficacy theory. In K. r. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 35-53). New York:Routledge.

Schunk, D.H. (2012) Learning theories: An educational perspective, 6th edition, First published 1991 Boston: Allyn & Bacon, Pearson Education Inc.

Statistically significant impact after only 100 minutes

1 March 2018People are usually intrigued when I explain that this reading programme requires only 100 minutes from start to finish. In fact, pupils do not necessarily need 100 minutes to accomplish the goals of the Rhythm for Reading programme. Often improved engagement, comprehension, ease, fluency and joy of reading can be achieved after one hour spread across six weeks. A six week programme works well for the majority of children but for some who unfortunately do not attend school consistently, it would be far too easy for them to fall behind. By simply increasing the total length of the Rhythm for Reading programme from 60 to 100 minutes, all the children have enough time to develop their rhythmic awareness and experience the benefits in their reading. When 100 minutes are spread across ten weekly sessions, the programme slots neatly into a school term and this is convenient for everyone.

I am often asked how it’s possible for pupils to make real progress in only ten minutes per week and how certain can we be that the impact is attributable to Rhythm for Reading? These are excellent questions. First of all, pupils are reading everyday in the classroom, so they have ample opportunity to apply the rhythm-based approaches that they learn in the weekly ten-minute sessions to every task that involves reading during the school day. Each ten-minute session acts as a powerful catalyst, aligning decoding skills with the natural language processing abilities of the pupils. As the approach is rhythm-based instead of word-based, pupils with specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia or English as an Additional Language (EAL) benefit hugely from the opportunity to improve their reading without using words. It’s an opportunity to lighten the cognitive load, but to intensify precision and finesse. Secondly, I made sure that Rhythm for Reading was among the first intervention programmes to be evaluated as part of the EEF initiative. In this trial, I chose not to exclude any pupils. This meant that some students that took part were unable to access the reading tests because they could not decode text at all. The randomised controlled trial showed scientifically that improved reading scores were attributable to participation in the Rhythm for Reading programme, even though it took only 100 minutes to complete.

Progressive action in schools

25 June 2017

The recent tragic events in London and Manchester have been deeply painful and have also been a sharp reminder of the importance of taking progressive action in education. In 2012, I embarked on an entrepreneurial journey because I wanted the benefits of rhythm-based learning to be available in classrooms everywhere, as well as to ensure that certain educational advantages that are available to the privileged who can afford high quality instrumental music tuition would be, in a condensed and concentrated format, available to all. We hear frequently about the importance of reading for the development of empathy, and in 2014, I decided to create a project which would combine the theme of empathy with rhythm-based activities, which enhance social cohesion, reading fluency, reading comprehension and engagement. With the help and support of the senior leadership teams of two neighbouring, but very different schools, Alleyn’s, an independent school, and Goodrich Community Primary School, we have established a bond based on empathy, cooperation, rhythm and reading.

The project has completed eight cycles so far. Each week a group of assured and enthusiastic Year12 Alleyn’s students have accompanied me to Goodrich School, where they have mentored wonderfully effervescent pupils in Year 3 and Year 4. Everybody benefits profoundly from taking part: the mentoring students quickly learn to build trust and communication with the younger children, who experience a remarkable transformation in their reading. I am very much looking forward to presenting on this topic on Saturday 1st July at the UKLA 53rd International Conference 2017 ‘Language, literacy and class: Connections and contradictions’ at Strathclyde University, Glasgow.

Discover the heartbeat of reading

7 January 2017BETT 2017 is just around the corner! In a few weeks, Rhythm for Reading will be taking part in The Great British Trail in partnership with the Department for International Trade (Stand D30). We will be sharing our ideas and vision with visitors using audio and video clips and other goodies. We’ll be on stand C62 and look forward to saying hello.

The Rhythm for Reading programme helps teachers and students to activate the rhythmic aspect of reading, which researchers are discovering is so important for building reading fluency and understanding.

Why not think of rhythm as the heartbeat of reading?

Just as a heartbeat is dynamic, adjusting to our every need, rhythm in reading is the adjustable quality that provides strength, responsiveness and flexibility as sentences of all shapes and sizes flow through the text.

Just as a heartbeat is organic, supporting life in each part of the body from the smallest cells to the largest organs, rhythm in reading reaches systemically into every part of language. Like a heartbeat it spreads both upwards, supporting the structure of phrases and sentences and also downwards, energising and sharpening the edges of syllables and phonemes. Rhythm therefore brings the different grain sizes of language into alignment with each other.

Sensitivity to the rhythmic cues in printed language can be developed very easily. In fact, we already use rhythm in everyday life to coordinate activities that we take for granted such as walking, talking and obviously, in our breathing. However, as reading is a socially learned activity, the rhythmic quality that is naturally present in language processing does not always map with ease onto decoding skills. This is why for some children reading does not become increasingly skilled over time, even when decoding skills are secure. Fortunately, sensitivity to rhythm in reading can be improved very quickly as these case studies show.

Look out for the next post in this series on rhythm at the heart of reading.

Releasing Resistance to Reading

1 January 2017

It may seem odd to post on the topic of resistance on the first day of the year, but let’s not forget that the flip side of a new resolution involves effort to override old patterns.

Resistance is the entrenched furrow that our everyday thoughts have engraved in our mind. We feel resistance when the initial impetus of the ‘new’ wears off and the familiar old way begins to reassert itself.

This is an uncomfortable topic as resistance is a potentially self-sabotaging behaviour. It has the power to divert our efforts to try new things, unleashing opportunities to face our old fears and stories. It is only when resistance is ‘released’ that the benefits of new behaviours become permanent and lasting change becomes possible.

In fact, some of my most rewarding and meaningful experiences in teaching have involved releasing children’s resistance to reading, teamwork, group teaching, moving in time with others and music. This has happened in a very short timeframe, as part of the process of developing reading fluency through the Rhythm for Reading programme.

Rhythm induces a state of flow and people often talk about getting into a ‘rhythm’ or a ‘groove’ as part of their creative process and also in relation to exercising. Language processing is also sensitive to rhythmic flow states, for example when we become absorbed by a book or when we write and find that the writing starts to flow.

Interviewed about the factors that interfered with flow states, (see last month’s post for more on this) Csikszentmilhalyi’s informants described, ‘aspects of normative life’ which included: a sense of unmanageable fear, the pressure to work to deadlines and clock-watching. There was a general orientation towards the final outcome rather than the process - in other words, the journey. A focus on extrinsic rewards and material gain and also social rewards also seemed to block people’s ability to find flow, which tells us something about effects of consumer culture of that time. Even at the turn of the century there was an awareness that becoming mentally distracted was a growing problem and people also reported a confusion of attention. Lastly, isolation from nature was described as a big factor in people’s loss of flow. Thankfully, almost twenty years later, we are now more aware of the therapeutic value of spending time in nature..

From this list, it seems that the conditions of contemporary life may not only impede the development of flow states, but also reinforce the experience of resistance. Many of the items on this list pop up in our homes, places of work, schools and classrooms. As we move forward into 2017, perhaps, a fresh look at our everyday lives could help us to find and maintain flow states and make time for opportunities to gently release resistance.

Csikszentmihalyi: (1975; 2000) Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing flow in work and play, 25th anniversary edition San Francisco, Jossey-Bass Inc.

Rhythmic elements in reading: From fluency to flow

4 December 2016In recent posts, I’ve described reading fluency as necessary for the experience of reading as a pleasurable and personally rewarding activity. The intrinsic rewards of reading for pleasure can lead individuals into a flow state, in which they describe being swept up or getting lost in a book and losing track of time.

A flow state is highly desirable as it is associated with efficiency, well-being and the development of expertise in many different fields. To understand the flow state phenomenon, Csikszentmihalyi interviewed expert surgeons, rock climbers and chess players who had developed their interest in each activity mainly for its intrinsic rewards, but also spoke about the element of risk involved. It is fascinating to consider that these individuals felt compelled to push hard against the limits of their knowledge and skills and actively challenged themselves in ways that forced them to develop their competence further.

A willingness to confront challenging situations, which involved a degree of risk, enabled these individuals to build systematically upon their knowledge, competency and skills, which in turn led to the development of their expertise. There are obvious dangers in surgery and rock-climbing, which put physical safety at risk, whereas in playing chess, the risk occurs at an abstract level involving the mental discipline and strength of each player. However, in each setting, the surgeons, rock-climbers and chess players experienced what Csikszentmihalyi described as a ‘merging of action and awareness’, which enabled them to focus all of their attention on their engagement with the activity (2000, p.149).

In studying the flow state, Csikszentmihalyi discovered patterns such as (i) move and counter-move in chess and (ii) movement and balance cycles in rock-climbing. These patterns of behaviour were key to achieving a state of relaxed alertness, described by one participant as a ‘self-contained universe’ (2000, p.40). Surprisingly, the similarities between the flow state described in high stress activities such as playing chess and rock-climbing can be compared with the more relaxing activity of reading for pleasure: this is similarly dependent on the coordination and maintenance of multiple skills, but with the addition of fluency of movement across printed words and the deployment of rhythmic sensitivity to the patterns within language.

Just as the natural rhythms of move versus countermove in chess and, movement versus balance involved in climbing induce a state of alert awareness, research into rhythm-based approaches to the teaching of reading has shown that developing pupils’ sensitivity to rhythm has allowed them to enjoy and understand what they read at the level of the phrase, the sentence and the narrative (Long, 2014). This state of pure involvement and learned sensitivity has enabled children to make extraordinary progress in only ten weeks - best of all, they now love to read. Read more.

Csikszentmihalyi: (1975; 2000) Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing flow in work and play, 25th anniversary edition San Francisco, Jossey-Bass Inc.

Long, M. (2014) ‘I can read further and there’s more meaning while I read’: An exploratory study investigating the impact of a rhythm-based music intervention on children’s reading, Research Studies in Music Education, 36 (1) , pp. 107-124