The Rhythm for Reading blog

All posts tagged 'comprehension'

Sensitivity to rhythm is all around us

14 November 2022A few weeks ago, in an inset session at a wonderful school with beautiful inclusive approaches in their group teaching, I mentioned that rats have the same limbic structures as humans. The limbic system is the part of the brain that deals with our mammalian instincts. These keep us in tune with social information, such as social status and hierarchy, protecting and nurturing our children, bonding with sexual partners and managing affiliation. It’s a logical assumption that if we share these limbic structures, rats like humans should be able to keep time with a musical beat - or their equivalent of that. So, it was no surprise to learn that Japanese researchers have shown that rats can indeed bob along and keep time with a musical beat.

It was back in the 1980s, when American scientists first discovered the genes that determined the rhythm of the mating song of fruit flies. If we think of rhythm as a musical trait exclusive to humans, these findings in rats and flies are simply amusing, novel or entertaining. On the other hand, the bigger picture behind these findings would suggest that the natural world is inherently structured by environmental and behavioural patterns organised by rhythm. If we think of rhythm as a system of ratios, proportions and repetition, then the math of rhythm is obvious. There are cycles and rhythmic flows in tides and weather systems and indeed, migration patterns follow these cycles. In individual organisms, as well as in shoal, pod, flock and herd movement, rhythmic patterns underpin locomotion and communication. Even a human infant’s stepping reflex is organised around the inherent rhythmic systems that we share with many other species.

We humans are particularly happy when our stylised rhythms achieve a hypnotic effect, for example in Queen’s ‘We will rock you,’ - one of the songs used by the Japanese scientists to detect the sensitivity to rhythm in rats. Halfway through the Rhythm for Reading programme, this same rhythmic pattern appears and is always greeted with enthusiasm by teachers and children as a fun part of the reading intervention. Look out for the next post, which explains the connection between hypnotic rhythm, flow states, reading fluency and reading comprehension.

When Rhythm & Phonemes Collide

7 November 2022

Have you ever taught a child with weak phonological awareness? The differences between sounds are poorly defined and individually sounds are swapped around. A lack of phonological discrimination could be explained by conflation. Conflation, according to the OED is the merging of two or more sets of information, texts, sets of ideas etc into one.

One of the most fascinating aspects of conflation is that it can happen at different levels of conscious awareness. So, for example teenagers learning facts about physics might conflate words such as conduction and convection. After all, these terms look similar on the page and are both types of energy transfer.

Younger children might conflate colours such as black and brown as both begin with the same phoneme and are dark colours. The rapid colour naming test in the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing reveals such conflation. For instance, a child I assessed once as part of a reading intervention conflated brown and green. Any brown or green square in the assessment was named ‘grouwn’ (it rhymed with brown). She had conflated the consonant blends of ‘br’ and ‘gr’ and invented a name for both colours.

In the early stages of reading, conflation can underpin confusion between consonant digraphs such as ‘ch’ and ‘sh’. Another typical conflation is ‘th’, and ‘ph’ (and ‘f’). In all of these examples, the sounds are similar and they differ only on their onset - the very beginning of the sound.

A child with sensitivity to rhythm is attuned to the onsets of the smallest sounds of language. In terms of rhythmic precision, the front edge of the sound is also the point at which the rhythmic boundary occurs. Children with a well-developed sensitivity to rhythm are also attuned to phonemes and are less likely to conflate the sounds. Logically, cultivating sensitivity to rhythm would help children to detect the onsets of phonemes at the early stages of reading. Stay tuned for Part 2 and a free infographic..

Education for Social Justice

5 September 2022

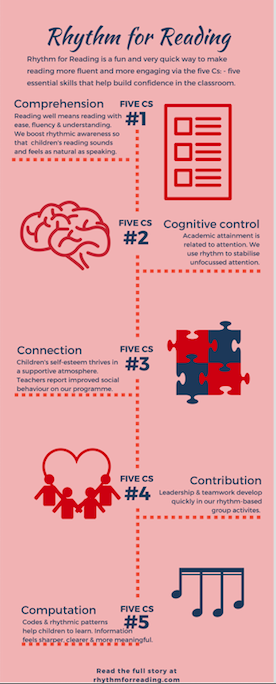

The Rhythm for Reading programme is deeply rooted in education for social justice. My personal mission is driven by my commitment to the development of inclusion in society, and built on the principle of equity in education.

I have worked in leading independent schools such as Alleyn’s, teaching the children from some of the country’s most privileged families, and yet I believe in empowering all children. I am writing this to share with you the mechanism that we can use together to raise standards in reading. Together, we can raise standards in reading and the Rhythm for Reading programme offers a mechanism to achieve this.

By empowering children with a lifelong love of reading, we can protect their mental health. An additional benefit of the Rhythm for Reading programme is that it launches the children into the world of musical notation, which they learn to read fluently, right from the start of the ten week intervention programme.

This is what we aim to do in Rhythm for Reading:

- to raise standards in reading.

- to empower staff to sustain those raised standards.

- to train staff, especially the support staff who are helping readers to develop fluency and enjoyment in their reading.

At Rhythm for Reading, we recognise that phonological processing requires:

- phonological knowledge (letter-sound correspondence),

- phonological awareness (sensitivity to the smallest sounds of language)

- awareness of the flow of sounds (rhythmic and grammatical context).

The data gathered from the past 10 years show that the Rhythm for Reading programme improves perceptual sensitivity:

- to the sounds of language,

- to the rhythmic flow of language,

- to the grammatical structure and consequently, the comprehension of language.

Children have reported many changes in their learning behaviour at the end of the ten weeks of the Rhythm for Reading programme, including:

- being able to follow their teacher’s instructions,

- knowing what is going on in the lesson,

- being able to get on with their work because they are able to ignore distractions.

If you would like to find out more, visit the contact page to get in touch and sign up for weekly insights.

Reading fluency and comprehension in 2020

9 November 2020

A strong correlation exists between reading fluency and comprehension - one that has fascinated researchers for many decades (Long, 2014). In our current climate, children who read fluently are more likely to cope well with blended learning, self-isolation and other restrictions of the global pandemic on schools.

How can we move more children into the fluent reader category?

Proficient readers automatically use the most appropriate strategy on the fly, whereas fragile readers are more likely to depend on a single strategy and to transition less efficiently from one strategy to another. A fluent reader however, is able to decode an unfamiliar word using phonological skills, as well as orchestrating contextual and syntactic cues to decode whole phrases.

So, there are many processes that are coordinated during fluent reading. Reading comprehension is a cornerstone of these. However, comprehension is not a ‘layer’ of reading that magically ‘appears’ because it has been mechanically underpinned by good levels of decoding and fluency. Comprehension is a product of rhythmic awareness - an important element of language acquisition in infancy.

Though well-intentioned, the practise of timing children’s reading with a stopwatch, encouraging them to read more quickly week after week is not helpful for cultivating rhythmic awareness. Using a stopwatch may generate a degree of motivation to read, but a focus on acceleration forces the child to read without finding their natural rhythm. In fact, if children have learned to decode at a fast pace, they have been trained to enunciate the words without understanding them at all. Comprehension is not related to the pace of reading.

Comprehension and word recognition are coordinated by rhythmic processes during fluent reading that are similar to the natural unfolding of rhythm during speaking and listening. A rhythm-based approach fosters rhythmic awareness and supports fluent reading.

Long, M. (2014). ‘I can read further and there’s more meaning while I read’: An exploratory study investigating the impact of a rhythm-based music intervention on children’s reading. Research Studies in Music Education, 36(1), 107-124.

Rhythm and Reading Comprehension 1/5

29 April 2018

‘To be understood - as to understand’ from the prayer of St Francis captures a profound truth: we are at our happiest when we feel truly understood by others. This feeling of mutual understanding strengthens communities and generates an aura of certainty at the core of each individual’s character. The ability to understand exists in all of us, but can easily be obscured by doubt, worry or fear. Removing worries, doubts and fears leads to clarity –as Johnny Nash put it, “I can see clearly now the rain has gone…”. The same principle applies to reading comprehension. The songlike qualities of speech (i.e. prosody) come to life in children’s voices when they are able to read with ease, fluency and understanding.

In the Simple View of Reading, reading comprehension is described as the ‘product of’ skilled decoding and linguistic comprehension (Gough & Tumner, 1986). The recent focus on oracy (for example Barton, 2018) highlights a focus in some schools on linguistic comprehension. According to researchers, the proportion of children beginning school with speech, language and communication needs is estimated at between 7 and 20 per cent (McKean, 2017) and unfortunately, communication issues carry a risk of low self-esteem and problems with self-confidence (Dockerall et al., 2017).

In the Gough & Tunmer model, the term ‘product of’ seems a little vague. I like to think that ‘product of’ refers to the flexible quality found in skilled reading as well as the dynamic integration of natural language with the alphabetic code. At first, beginning readers struggle to accommodate words and sentences of a variety of shapes and lengths, but as they become more skilled, they ease into a state of flexible, responsive reading, which leads to being able to read sentences whilst processing meaning at the same time. What is even more remarkable about this process is that reading with this wonderful flexibility takes place within distinct time constraints.

The time constraints are a kind of rhythmic signature for language comprehension as well as music and are biologically determined (Long, 2006). Each and every line of a song, poem or musical phrase typically lasts for 3-5 seconds. This brief ‘window’ is our subjective sense of the present moment (Gerstner & Fazio, 1995). In a song, a poem or a musical phrase, this moment is packed with messages and meanings – relating information about feeling, being or doing. The rhythm of reading in any language is very flexible indeed, but it is underpinned by this constant ebb and flow of units of meaning every 3-5 seconds. Becoming aligned with this natural flow of meaning helps children to read words, phrases and sentences with ease, fluency and understanding and also to anticipate words and phrases prior to reading them.

The importance of this rhythmic ebb and flow of meaning cannot be overstated and is a core part of the Rhythm for Reading programme. The programme uses music rather than words to develop rhythmic sensitivity, so it is suitable for children and young people who need a sharp ‘boost’ in reading comprehension, language and communication skills, phonological awareness or cognitive control, whether attending mainstream or special schools.

Barton, G “Teachers should encourage pupils to speak up – and should remember to do so themselves TES News https://www.tes.com/news/teachers-should-encourage-students-speak-and-remember-do-so-themselves Retrieved on 29.4.2018

Dockrell, Julie Elizabeth, et al. “Children with Speech Language and Communication Needs in England: Challenges for Practice.” Frontiers in Education. Vol. 2. Frontiers, 2017.

Gerstner, Geoffrey E., and Victoria A. Fazio. “Evidence of a universal perceptual unit in mammals.” Ethology 101.2 (1995): 89-100.

Gough, Philip B., and William E. Tunmer. “Decoding, reading, and reading disability.” Remedial and special education 7.1 (1986): 6-10.

Long, M. “Stamping, clapping and chanting: An ancient learning pathway?” Educate Journal, 3, 1, (2006) 11-25

McKean, Cristina, et al. “Language Outcomes at 7 Years: Early Predictors and Co-Occurring Difficulties.” Pediatrics(2017): e20161684.

Statistically significant impact after only 100 minutes

1 March 2018People are usually intrigued when I explain that this reading programme requires only 100 minutes from start to finish. In fact, pupils do not necessarily need 100 minutes to accomplish the goals of the Rhythm for Reading programme. Often improved engagement, comprehension, ease, fluency and joy of reading can be achieved after one hour spread across six weeks. A six week programme works well for the majority of children but for some who unfortunately do not attend school consistently, it would be far too easy for them to fall behind. By simply increasing the total length of the Rhythm for Reading programme from 60 to 100 minutes, all the children have enough time to develop their rhythmic awareness and experience the benefits in their reading. When 100 minutes are spread across ten weekly sessions, the programme slots neatly into a school term and this is convenient for everyone.

I am often asked how it’s possible for pupils to make real progress in only ten minutes per week and how certain can we be that the impact is attributable to Rhythm for Reading? These are excellent questions. First of all, pupils are reading everyday in the classroom, so they have ample opportunity to apply the rhythm-based approaches that they learn in the weekly ten-minute sessions to every task that involves reading during the school day. Each ten-minute session acts as a powerful catalyst, aligning decoding skills with the natural language processing abilities of the pupils. As the approach is rhythm-based instead of word-based, pupils with specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia or English as an Additional Language (EAL) benefit hugely from the opportunity to improve their reading without using words. It’s an opportunity to lighten the cognitive load, but to intensify precision and finesse. Secondly, I made sure that Rhythm for Reading was among the first intervention programmes to be evaluated as part of the EEF initiative. In this trial, I chose not to exclude any pupils. This meant that some students that took part were unable to access the reading tests because they could not decode text at all. The randomised controlled trial showed scientifically that improved reading scores were attributable to participation in the Rhythm for Reading programme, even though it took only 100 minutes to complete.

Progressive action in schools

25 June 2017

The recent tragic events in London and Manchester have been deeply painful and have also been a sharp reminder of the importance of taking progressive action in education. In 2012, I embarked on an entrepreneurial journey because I wanted the benefits of rhythm-based learning to be available in classrooms everywhere, as well as to ensure that certain educational advantages that are available to the privileged who can afford high quality instrumental music tuition would be, in a condensed and concentrated format, available to all. We hear frequently about the importance of reading for the development of empathy, and in 2014, I decided to create a project which would combine the theme of empathy with rhythm-based activities, which enhance social cohesion, reading fluency, reading comprehension and engagement. With the help and support of the senior leadership teams of two neighbouring, but very different schools, Alleyn’s, an independent school, and Goodrich Community Primary School, we have established a bond based on empathy, cooperation, rhythm and reading.

The project has completed eight cycles so far. Each week a group of assured and enthusiastic Year12 Alleyn’s students have accompanied me to Goodrich School, where they have mentored wonderfully effervescent pupils in Year 3 and Year 4. Everybody benefits profoundly from taking part: the mentoring students quickly learn to build trust and communication with the younger children, who experience a remarkable transformation in their reading. I am very much looking forward to presenting on this topic on Saturday 1st July at the UKLA 53rd International Conference 2017 ‘Language, literacy and class: Connections and contradictions’ at Strathclyde University, Glasgow.

Discover the heartbeat of reading

7 January 2017BETT 2017 is just around the corner! In a few weeks, Rhythm for Reading will be taking part in The Great British Trail in partnership with the Department for International Trade (Stand D30). We will be sharing our ideas and vision with visitors using audio and video clips and other goodies. We’ll be on stand C62 and look forward to saying hello.

The Rhythm for Reading programme helps teachers and students to activate the rhythmic aspect of reading, which researchers are discovering is so important for building reading fluency and understanding.

Why not think of rhythm as the heartbeat of reading?

Just as a heartbeat is dynamic, adjusting to our every need, rhythm in reading is the adjustable quality that provides strength, responsiveness and flexibility as sentences of all shapes and sizes flow through the text.

Just as a heartbeat is organic, supporting life in each part of the body from the smallest cells to the largest organs, rhythm in reading reaches systemically into every part of language. Like a heartbeat it spreads both upwards, supporting the structure of phrases and sentences and also downwards, energising and sharpening the edges of syllables and phonemes. Rhythm therefore brings the different grain sizes of language into alignment with each other.

Sensitivity to the rhythmic cues in printed language can be developed very easily. In fact, we already use rhythm in everyday life to coordinate activities that we take for granted such as walking, talking and obviously, in our breathing. However, as reading is a socially learned activity, the rhythmic quality that is naturally present in language processing does not always map with ease onto decoding skills. This is why for some children reading does not become increasingly skilled over time, even when decoding skills are secure. Fortunately, sensitivity to rhythm in reading can be improved very quickly as these case studies show.

Look out for the next post in this series on rhythm at the heart of reading.