The Rhythm for Reading blog

Rhythm and Connection 3 / 5

2 September 2018

The new school year is about to start and for the young people transferring to secondary school, September will bring new friendships, new relationships with teachers as well as new journeys to and from school. A few years ago I worked on a fascinating research project about secondary school transfer across England, interviewing 24 young people at four points in time. The young adolescents left their primary schools full of positivity and high expectations, anticipating with relish many new friendships and exciting opportunities.

I heard about novelty, new ideas, a fresh perspective, a change of environment, hope, excitement and fulfilment. Moving beyond the limits of primary school was a very strong theme - though the young people stressed the importance of maintaining strong connections with their ‘old’ friends, meeting them at weekends to enjoy ‘messing about’ (dancing and singing to their favourite songs), whereas socialising with their ‘new’ friends after school involved talking and listening to one another’s music. Isn’t this contrast interesting? Music appears incredibly important for building deeper social connections.

Looking at everyday social behaviour, music is woven into our lives at a personal level as well as at the level of musical experiences in the wider community. For example, personal musical preferences are important at an individual level, such as when singing and dancing with infants and children, sustaining attention on tasks and work, forming romantic relationships and even in resolving problems with health. However, music is also used more publicly for celebrations in families, social groups, workplaces and communities.

Broadly speaking, it seems that music that we are exposed to via mass media may help to relax vigilance, inhibition, scepticism and caution. Film makers for example regard music as essential in helping their audience to suspend their disbelief, to relax their critical judgement, to be more easily persuaded by the special effects as well as being captivated by the fiction, the drama and characters. What might explain this?

Humans are mammals and to some extent tend to revert to socially instinctive behaviour when socially uninhibited. Studies of other mammals such as rats and mice have shown that social signals related to mating, nurturing or protecting young are processed in the mid-brain.Remarkably, tiny mice pups produce ultra-sonic squeaks when separated from the rest of the litter and scientists have shown that only mother mice actually hear these high frequencies (Liu et al, 2006; Liu et al., 2007). Since, many mammal species commit infanticide, this specialised form of social signal is highly advantageous, ensuring that the vulnerable pups have a greater chance of survival.

Mythical tales of abandonment, involving fear of the jaws of death followed by the joy of reunion are familiar themes in stories from all around the world. Sound is a primal medium of connection and communication via mid brain processes that are rapid, subjective, subtle and subconscious. Similarly, the telling of stories, the recitation of poems and songs are also examples of how auditory signals are woven together to communicate for example fear, distress and joyful reunion, or other emotions. Telling a story involves a particular style of social engagement known as entrainment, drawing people in, encouraging them to lean into the tale using a particular blend of structure and rhythm and emotional processing. The auditory structures allow listeners to suspend their disbelief, to step inside the story with the narrator creating a state of seeming emotional safety. The use of descriptive language to convey the affect (emotional content) of the narrative may help individuals and communities to process disturbing feelings within a structure, a contextual framework of time and space. The structure allows the tale to be retold and remembered for future social gatherings.

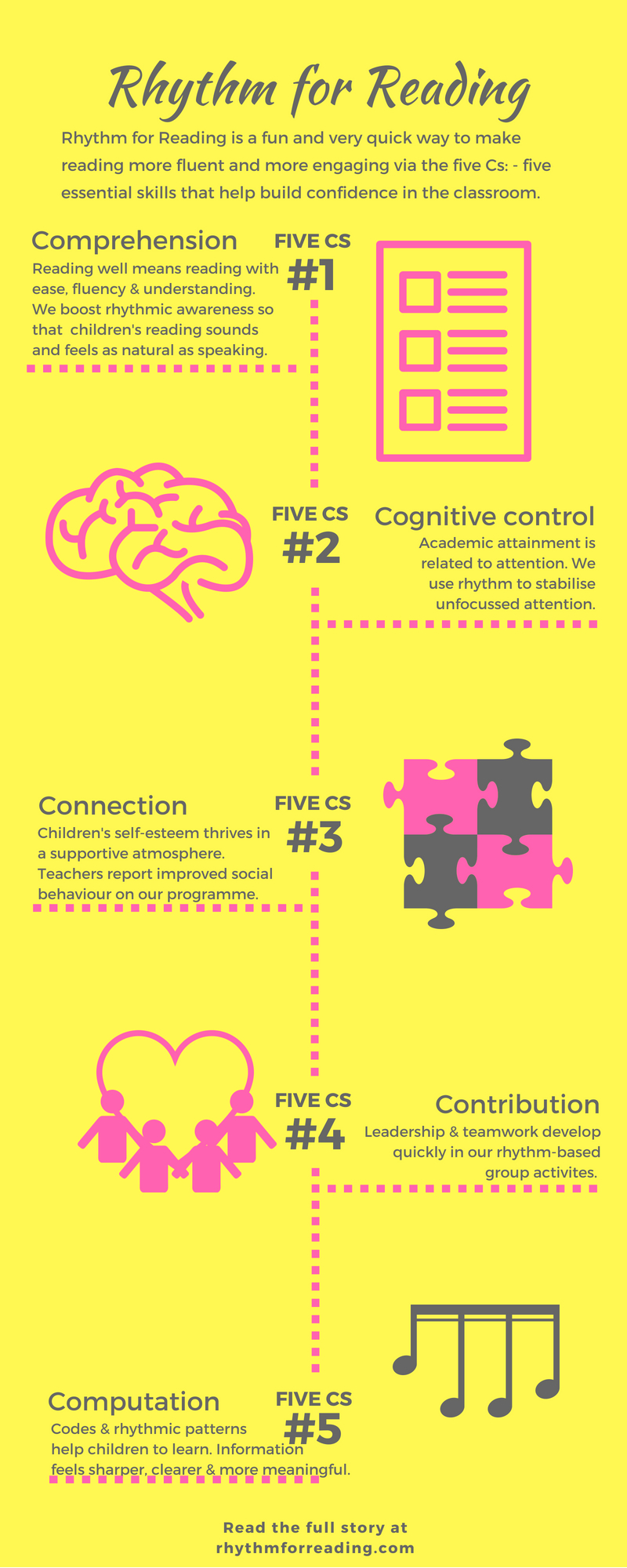

In Rhythm for Reading, the entrainment process involves the sharing of motion, affect, the chanting of rhythmic patterns within musical structures. The specially composed musical resources create the time and space for this type of social engagement. Although this is a reading intervention that doesn’t use words, here are some case studies, demonstrating changes in reading after taking part in our rhythm-based group entrainment exercises.

Liu RC, Linden JF, Schreiner CE. 2006. Improved cortical entrainment to infant communication calls in mothers compared with virgin mice. Eur J Neurosci 23:3087–3097.

Liu RC, Schreiner CE. 2007. Auditory cortical detection and discrimination correlates with communicative significance. PLoS Biol 5:e173.