The Rhythm for Reading blog

All posts tagged 'inclusive-approaches'

Sensitivity to rhythm is all around us

14 November 2022A few weeks ago, in an inset session at a wonderful school with beautiful inclusive approaches in their group teaching, I mentioned that rats have the same limbic structures as humans. The limbic system is the part of the brain that deals with our mammalian instincts. These keep us in tune with social information, such as social status and hierarchy, protecting and nurturing our children, bonding with sexual partners and managing affiliation. It’s a logical assumption that if we share these limbic structures, rats like humans should be able to keep time with a musical beat - or their equivalent of that. So, it was no surprise to learn that Japanese researchers have shown that rats can indeed bob along and keep time with a musical beat.

It was back in the 1980s, when American scientists first discovered the genes that determined the rhythm of the mating song of fruit flies. If we think of rhythm as a musical trait exclusive to humans, these findings in rats and flies are simply amusing, novel or entertaining. On the other hand, the bigger picture behind these findings would suggest that the natural world is inherently structured by environmental and behavioural patterns organised by rhythm. If we think of rhythm as a system of ratios, proportions and repetition, then the math of rhythm is obvious. There are cycles and rhythmic flows in tides and weather systems and indeed, migration patterns follow these cycles. In individual organisms, as well as in shoal, pod, flock and herd movement, rhythmic patterns underpin locomotion and communication. Even a human infant’s stepping reflex is organised around the inherent rhythmic systems that we share with many other species.

We humans are particularly happy when our stylised rhythms achieve a hypnotic effect, for example in Queen’s ‘We will rock you,’ - one of the songs used by the Japanese scientists to detect the sensitivity to rhythm in rats. Halfway through the Rhythm for Reading programme, this same rhythmic pattern appears and is always greeted with enthusiasm by teachers and children as a fun part of the reading intervention. Look out for the next post, which explains the connection between hypnotic rhythm, flow states, reading fluency and reading comprehension.

When Rhythm and Phonics Collide Part 2

11 November 2022In my last post I described a typical challenge facing a child with poor phonological awareness. Using a rapid colour naming test (CToPP2), it’s possible to identify that a weakness in processing the smallest sounds of language often occurs at the onset of a phoneme, in other words the onset of a syllable. Consonant blends and consonant digraphs are more affected, so, conflation between ‘thr’ and ‘fr’, or ‘cl’ and ‘gl’ is likely to happen and to impede the development of reading with ease and fluency.

The notion that sensitivity to both rhythm and the smallest sounds of language overlap in terms of data has been around for decades. A positive correlation between sensitivity to rhythm and phonemic sensitivity has been shown in many studies. It’s easy to understand that rhythm and phonological processing overlap if we consider that the start of a phoneme - the onset of a syllable is exactly where sensitivity to rhythm is measured - whether that’s the start of a musical sound or a spoken utterance.

Thinking for a moment about words that begin with a consonant, imagine focussing mostly on the vowel sound of each syllable, without being able to discern the shape of the initial phoneme with sufficient clarity. The sounds would merge together into a kind of ambient speech puddle.

Vowel sounds carry interesting information such as emotion, or tone of voice. They are longer (in milliseconds) and without defined edges. Now imagine focussing on the onset of those syllables. The consonants are shorter (in milliseconds), more sharply defined and more distinctive, leaving plenty of headspace for cognitive control. If consonants are prioritised, information flows easily and the message lands with clarity.

The Rhythm for Reading programme addresses these distinctions through group teaching that is fun and supports early reading in particular. Information processing is enhanced by sensitivity to rhythm because rhythm focusses attention onto the onset of the sound, which is where the details are sharpest. This kind of information processing remain effortless, easy and fluent.

If you’d like to know a little more about this, the details are summarised in a free infographic. Click here.

When Rhythm & Phonics Collide

7 November 2022

Have you ever taught a child with weak phonological awareness? The differences between sounds are poorly defined and individually sounds are swapped around. A lack of phonological discrimination could be explained by conflation. Conflation, according to the OED is the merging of two or more sets of information, texts, sets of ideas etc into one.

One of the most fascinating aspects of conflation is that it can happen at different levels of conscious awareness. So, for example teenagers learning facts about physics might conflate words such as conduction and convection. After all, these terms look similar on the page and are both types of energy transfer.

Younger children might conflate colours such as black and brown as both begin with the same phoneme and are dark colours. The rapid colour naming test in the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing reveals such conflation. For instance, a child I assessed once as part of a reading intervention conflated brown and green. Any brown or green square in the assessment was named ‘grouwn’ (it rhymed with brown). She had conflated the consonant blends of ‘br’ and ‘gr’ and invented a name for both colours.

In the early stages of reading, conflation can underpin confusion between consonant digraphs such as ‘ch’ and ‘sh’. Another typical conflation is ‘th’, and ‘ph’ (and ‘f’). In all of these examples, the sounds are similar and they differ only on their onset - the very beginning of the sound.

A child with sensitivity to rhythm is attuned to the onsets of the smallest sounds of language. In terms of rhythmic precision, the front edge of the sound is also the point at which the rhythmic boundary occurs. Children with a well-developed sensitivity to rhythm are also attuned to phonemes and are less likely to conflate the sounds. Logically, cultivating sensitivity to rhythm would help children to detect the onsets of phonemes at the early stages of reading. Stay tuned for Part 2 and a free infographic..

Empowering children to read musical notation fluently

4 November 2022

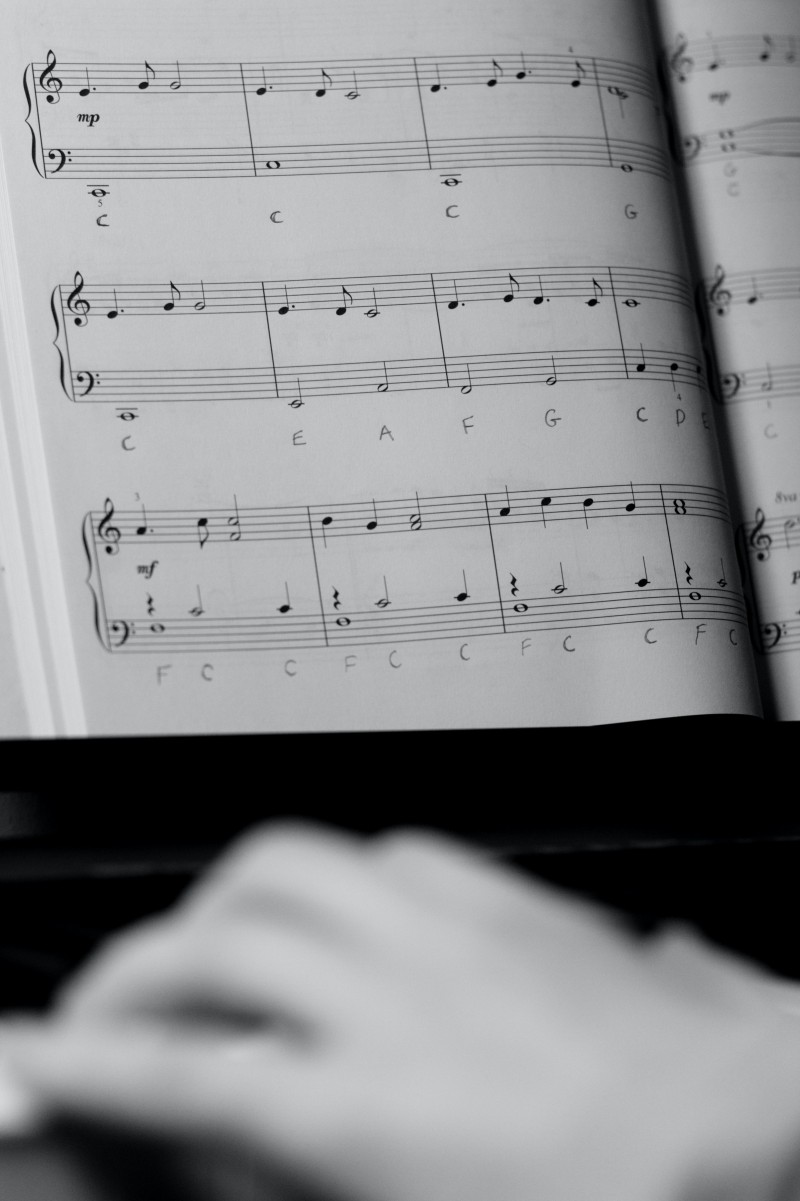

Schools face significant challenges in deciding how best to introduce musical notation into their curriculum. Resources are already stretched. Some pupils are already under strain because they struggle with reading in the core curriculum. The big question is how to integrate musical notation into curriculum planning in a way that empowers not only the children, but also the teachers.

There are tried and tested ways of teaching musical notation which transcend age, and are best suited to pupils who process information with ease. Traditionally, piano teachers begin with mnemonics for the notes that sit on the lines of the stave EGBDF (Every Good Boy Deserves Favour) GBDFA (Good Boys Deserve Fun Always) and for the notes that sit on the spaces FACE (Face) and ACEG (All Cows Eat Grass). Many teachers use these mnemonics to introduce a series of line notes and / or space notes all at once, which creates a heavy cognitive load.

What about all the children who struggle to process information, reading with ease and fluency?

The tried and tested method of adapting musical notation for children who struggle to process the information, is to add more information and increase he cognitive load even more.

What’s on earth is going on here?

Music teachers want children to enjoy making music and to have fun producing sounds on their instruments and they hope that in time, reading notation will gradually become familiar and easier to read. Until that point, music teachers add extra information to remind the child of the letter names of the notes. In the same vein, music teachers often add numbers representing the finger patterns, to remind the child how to produce sounds on the instrument.

Soon enough, the page is cluttered with markings and the child has to select which markings to read.

These markings are intended as a quick fix, aiming to keep the child engaged, but they inevitably become reliant on the letters, or the numbers, or both. This approach sets the child up to fail in the sense that they do not learn to read notation at all and believe that it is too difficult for them.

What could teachers do differently to support children who do not process information with ease and fluency?

A more inclusive approach would limit the cognitive load on children’s reading - which is what we do in the Rhythm for Reading Programme. Rather than teaching all the notes at once, we focus on just a few notes and develop fluency and fun in reading right form the start. Instead of learning musical notes at the same time as playing musical instruments, which adds to the cognitive load, we simply use our feet, our hands and our voices, as we believe these are our most natural musical instruments.

Group learning in a structured programme supports the development of fluency, because the children are nurtured by the ethos of working together. Teamwork in combination with rhythm is an effective way to build fluency in reading, and acts as a catalyst for progress.

“I used to say things quite slow, but now I say them fast”

15 April 2015As educators we are required to make thousands of small but important decisions everyday. Striking the right balance involves blending professional judgement with our integrity and experience. Through reflection perhaps with colleagues, we are constantly learning from our experiences.

I have been thinking hard about special education (SEND) recently. The Rhythm for Reading programme promotes inclusive approaches. Students with learning differences are fully involved alongside their classmates and the programme is accessible even to those who cannot yet read simple words such as ‘cat’. This is what a child said recently to me about the programme: “I liked how we had to keep it in the team at the same time. I felt more surrounded. I had people to keep me upright.” So, when a pupil shows absolutely no desire to contribute to even the most basic of Rhythm for Reading exercises, whilst all around him others are learning rapidly and having fun, my own personal learning journey fires up in a big way.

Each Rhythm for Reading session is only ten minutes long and so every second is precious. Is this child withdrawn, overwhelmed, lacking in confidence, lacking social skills, frightened or generally resistant to new things? What is clear and of concern to me is that he is ignored by the other children and hardly responds to anything I say or do. His teachers are highly protective of him and they can recite a list of issues and medical problems: he is a special child.

I believe that if a child processes and performs tasks more slowly than his classmates, as educators we must help him to develop the strategies that he needs to adapt to different settings. Self-regulation strategies for example, are key for learning road safety skills: learning to judge the speed of traffic, inhibiting the impulse to wander into the road, as well as being able to find a safe place to cross are essential to every child’s survival, no matter how special that child’s needs might be. While road safety lessons are clearly a matter of life and death, it is the quality of life of each child that is determined in the classroom. To teach a special child to cope with a broad range of settings with confidence is a highly worthwhile investment of our time and energy. There are so many benefits of joining in with others in a structured group teaching activity. It is enormous fun and a profound sense of belonging and unity develops through cooperation. Of course, this outcome can only be fully enjoyed by everyone, if everyone has contributed wholeheartedly to the success of the task.

If you have enjoyed this blog, you might also like to learn more about our work on metacognition and self-regulation. If you’d like more information about the programme, contact me direct, or sign up for free weekly ‘Insights’, which launches next week!